One of the conspiracy theories that has plagued attempts to keep people informed during the pandemic is the idea that the coronavirus was created in a laboratory. But the vast majority of scientists who have studied the virus agree that it evolved naturally and crossed into humans from an animal species, most likely a bat.

How exactly do we know that this virus, SARS-CoV-2, has a "zoonotic" animal origin and not an artificial one? The answers lie in the genetic material and evolutionary history of the virus, and understanding the ecology of the bats in question.

An estimated 60 percent of known infectious diseases and 75 percent of all new, emerging, or re-emerging diseases in humans have animal origins. SARS-CoV-2 is the newest of seven coronaviruses found in humans, all of which came from animals, either from bats, mice or domestic animals.

Bats were also the source of the viruses causing Ebola, rabies, Nipah and Hendra virus infections, Marburg virus disease, and strains of Influenza A virus.

The genetic makeup or "genome" of SARS-CoV-2 has been sequenced and publicly shared thousands of times by scientists all over the world. If the virus had been genetically engineered in a lab there would be signs of manipulation in the genome data.

This would include evidence of an existing viral sequence as the backbone for the new virus, and obvious, targeted inserted (or deleted) genetic elements.

But no such evidence exists. It is very unlikely that any techniques used to genetically engineer the virus would not leave a genetic signature, like specific identifiable pieces of DNA code.

The genome of SARS-CoV-2 is similar to that of other bat coronaviruses, as well as those of pangolins, all of which have a similar overall genomic architecture. Differences between the genomes of these coronaviruses show natural patterns typical of coronavirus evolution. This suggests that SARS-CoV-2 evolved from a previous wild coronavirus.

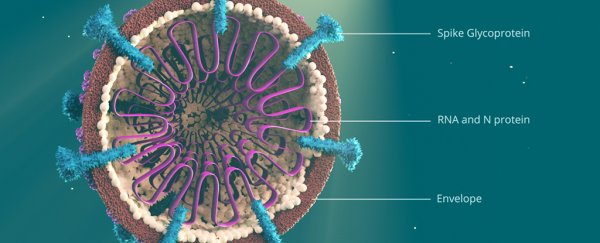

One of the key features that makes SARS-CoV-2 different from the other coronaviruses is a particular "spike" protein that binds well with another protein on the outside of human cells called ACE2. This enables the virus to hook into and infect a variety of human cells.

However, other related coronaviruses do have similar features, providing evidence that they have evolved naturally rather than being artificially added in a lab.

Coronaviruses and bats are locked in an evolutionary arms race in which the viruses are constantly evolving to evade the bat immune system and bats are evolving to withstand infections from coronaviruses. A virus will evolve multiple variants, most of which will be destroyed by the bat's immune system, but some will survive and pass to other bats.

Some scientists have suggested that SARS-CoV-2 may have come from another known bat virus (RaTG13) found by researchers at the Wuhan Institute of Virology. The genomes of these two viruses are 96% similar to one another.

This might sound very close but in evolutionary terms this actually makes them significantly different and the two have been shown to share a common ancestor. This shows that RaGT13 is not the ancestor of SARS-CoV-2.

In fact, SARS-CoV-2 most likely evolved from a viral variant that couldn't survive for a long period of time or that persists at low levels in bats.

Coincidentally, it evolved the ability to invade human cells and accidentally found its way into us, possibly by means of an intermediate animal host, where it then thrived. Or an initially harmless form of the virus might have jumped directly into humans and then evolved to become harmful as it passed between people.

Genetic variations

The mixing or "recombination" of distinct coronavirus genomes in nature is one of the mechanisms that brings about novel coronaviruses. There is now further evidence that this process could be involved in the generation of SARS-CoV-2.

Since the pandemic started, the SARS-CoV-2 virus appears to have started evolving into two distinct strains, acquiring adaptations for more efficient invasion of human cells. This could have occurred through a mechanism known as a selective sweep, through which beneficial mutations help a virus to infect more hosts and so become more common in the viral population.

This is a natural process that can ultimately reduce the genetic variation between individual viral genomes.

The same mechanism would account for the lack of diversity seen in the many SARs-CoV-2 genomes that have been sequenced. This indicates that the ancestor of SARS-CoV-2 could have been circulating in bat populations for a considerable amount of time. It then would have acquired the mutations that allowed it to spill over from bats into other animals, including humans.

It is also important to remember that around one in five of all mammal species on Earth are bats, with some found only in certain locations and others migrating across vast distances. This diversity and geographical spread makes it a challenge to identify which group of bats SARS-CoV-2 originally came from.

There is evidence that early cases of COVID-19 occurred outside of Wuhan in China and had no clear link to the city's wet market where the pandemic is thought to have begun. But that isn't evidence of a conspiracy.

It could simply be that infected people accidentally brought the virus into the city and then the wet market, where the enclosed, busy conditions increased the chances of the disease spreading rapidly.

This includes the possibility of one of the scientists involved in bat coronavirus research in Wuhan unknowingly becoming infected and bringing the virus back from where their subject bats lived. This would still be considered natural infection, not a laboratory leak.

Only through robust science and the study of the natural world will we be able to truly understand the natural history and origins of zoonotic diseases like COVID-19. This is pertinent because our ever-changing relationship and increasing contact with wildlife is raising the risk of new deadly zoonotic diseases emerging in humans.

SARS-CoV-2 is not the first virus that we have acquired from animals and certainly will not be the last. ![]()

Polly Hayes, Lecturer in Parasitology and Medical Microbiology, University of Westminster.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.