We humans are very curious about the nuclear furnace that powers life on Earth. We've looked at the Sun in so many different ways, both Earth-based and space-based. Yet we've had a really hard time getting a glimpse of its poles.

Now a solar mission has given us just that, in the form of an image pieced together from data collected by the European Space Agency's PROBA-2 (PRoject for OnBoard Autonomy 2) satellite, in orbit around Earth.

Our home planet - and most of the stuff in the Solar System - orbits the Sun in a more-or-less flat plane, close to the star's equator. This is called the ecliptic plane, and it's the result of the flat disc of dust and gas that whirled around the baby Sun, from which the planets formed.

We also launch spacecraft out on the ecliptic plane, for a practical reason. The spin of Earth on its axis gives a rocket a bit of a boost, meaning it takes less effort to get it into space. The closer the launch is to the equator, the greater the boost. It would be a lot harder to launch a rocket from Earth's polar regions.

So rockets launched from Earth are already travelling in the ecliptic plane and therefore normally aren't in a position to peek at the Sun's poles. It is possible to get out of this plane, but it's quite hard and time-consuming.

There has actually been one probe that looked at the Sun's poles, though. NASA, the ESA and the Canadian National Science Council collaborated on Ulysses, which looped over the top of the Sun's poles at a distance of nearly 322 million kilometres (200 million miles). That's over twice the average distance between Earth and the Sun.

It was an absolute unit of a feat. They had to send the probe all the way out to Jupiter. Then, once it got there, they had to slow it down to nearly nothing, then use Jupiter's gravity to fling Ulysses up out of the ecliptic plane.

It then made just three enormous loops of the Sun over 15 years, from 1994 to 2009. And we learnt a lot from Ulysses - but none of its instruments were a camera.

All this is the reason why we've never been able to actually see either of the Sun's poles directly with our eyes.

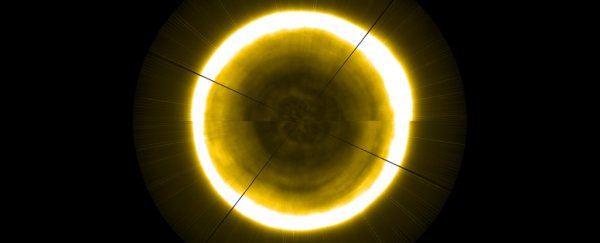

This time, we're not looking at a photograph either, strictly speaking - but it's likely very close.

"While the poles cannot be seen directly, when spacecraft observe the solar atmosphere they gather data on everything along their line of sight, also viewing the atmosphere extending around the disc of the Sun," the ESA explained.

"Scientists can use this to infer the appearance of the polar regions."

Slice by tiny slice, as the Sun rotates, PROBA-2 takes readings of these elements in extreme ultraviolet wavelengths, then combines them into a reconstruction of the Solar poles.

You can see the lines between the individual slices, and the line across the middle is created because of small changes in the solar atmosphere over the timeframe in which the data was collected.

ESA scientists have been building these images since June of this year, uploading them into a database so that they can observe how the Sun's poles change over time.

This is so that they can build on the knowledge gleaned by Ulysses, and try to learn more about the dynamics of solar phenomena at the polar regions - such as coronal holes, Alfvén waves and Rossby waves.

NASA's Parker Solar Probe, launched earlier this year, has already gotten closer to the Sun than any spacecraft before. But it's not going to leave the ecliptic plane.

For actual photos, we may have to wait for ESA's Solar Orbiter, scheduled for launch in 2020. It's not going to orbit the poles, but it's going to zoom around at high-enough latitudes that it will be able to image those mysterious and elusive regions.