It's a rumour that just won't die. When asked whether the COVID-19 virus was genetically engineered in a lab, scientists have already said "no" rather firmly, but the matter of the new coronavirus' origin is unlikely to be put to rest so easily.

Discussions around this subject have become even more pertinent since US government intelligence officials are reportedly investigating the potential source of the pandemic, focussing on theories that it may have originated in a laboratory, despite all evidence pointing to SARS-CoV-2 not being human-made.

"All evidence so far points to the fact the COVID-19 virus is naturally derived and not man-made," explains immunologist Nigel McMillan from the Menzies Health Institute Queensland.

"If you were going to design it in a lab the sequence changes make no sense as all previous evidence would tell you it would make the virus worse. No system exists in the lab to make some of the changes found."

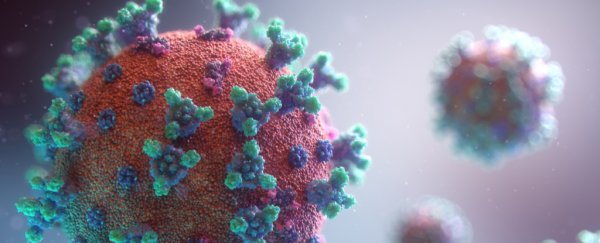

Back in late March, we covered a study published in Nature Medicine, in which the researchers investigated the genomic data of SARS-CoV-2 - particularly the receptor-binding domain (RBD) sections of the virus - to try and discover how it mutated into the virulent and deadly version we're currently struggling to contain.

As a by-product of their research, they were able to determine that SARS-CoV-2 was not genetically manipulated.

"By comparing the available genome sequence data for known coronavirus strains, we can firmly determine that SARS-CoV-2 originated through natural processes," one of the researchers, Scripps Research immunologist Kristian Andersen, said at the time.

"Two features of the virus, the mutations in the RBD portion of the spike protein and its distinct backbone, rules out laboratory manipulation as a potential origin for SARS-CoV-2."

Although it is clear the virus was not created in the lab, there have been ongoing concerns it may have 'escaped' a research facility, with most of the speculation - understandably - focussed on the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV). However, it remains just speculation. The Washington Post recently reported that US embassy officials had safety concerns about the lab back in 2018, and the institute did keep a closely related bat virus - but even that's far from a smoking gun.

"The closest known relative of SARS-CoV-2 is a bat virus named RaTG13, which was kept at the WIV. There is some unfounded speculation that this virus was the origin of SARS-CoV-2," explains University of Sydney evolutionary virologist, Edward Holmes.

"However, RaTG13 was sampled from a different province of China (Yunnan) to where COVID-19 first appeared and the level of genome sequence divergence between SARS-CoV-2 and RaTG13 is equivalent to an average of 50 years (and at least 20 years) of evolutionary change."

Now, it is important to note that viruses can mutate naturally anywhere - in animal hosts, in humans, or even in laboratory cell cultures. Unfortunately, it's difficult to determine where and how the new coronavirus acquired its mutations, although most researchers think the process involved an animal host.

Additionally, researchers are still investigating if the necessary mutations for causing the new disease occurred before or after SARS-CoV-2 made the jump to humans.

The institute at the centre of the controversy has repeatedly denied accusations of being the source of the pandemic. Back in March, head of bat coronavirus research at WIV, Shi Zhengli, explained that when she first received samples from early COVID-19 patients, she immediately did a thorough investigation at her department, finding no match between the viruses her lab had been working on, and COVID-19 patients.

"That really took a load off my mind," she told Scientific American. "I had not slept a wink for days."

What experts do agree on is that a pandemic like this is no surprise. Scientists have been warning governments for years that a new disease was on the horizon, and that many countries were woefully under-prepared.

For example, the director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Anthony Fauci, told the incoming US government administration in January 2017 about the inevitability of a "surprise outbreak", urging them to make preparations.

"We've been aware for some time that another coronavirus, like SARS and MERS before it, could cause a pandemic, and so in many ways, the emergence of a new coronavirus with pandemic potential is not a surprise," explains La Trobe University epidemiologist Hassan Vally.

"We have to be careful to not aid those irresponsibly using this global crisis for political point-scoring by giving any oxygen to these and other rumours."