After weeks of silence and denials, Russia has confirmed that it too has detected evidence of a mysterious radiation cloud floating above much of Europe, observing a dramatic radiation spike above Russia's Ural Mountains.

The acknowledgement comes after a number of other European nations suggested Russia was the probable origin of the unexplained radiation surge, which was first detected by numerous monitoring stations back in September.

Up until this point, Russian authorities had only disclosed they were not aware of any nuclear accidents on their turf, issuing a statement saying "[n]one of the enterprises of the Russian nuclear industry has recorded radiation levels that exceed the norm".

But now Russia's meteorological service, Roshydromet, has for the first time corroborated findings made by the French Institute for Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety (IRNS).

They acknowledged "extremely high contamination" above the Ural Mountains, detecting levels of the radioactive isotope ruthenium–106 up to almost 1,000 times the normal amount.

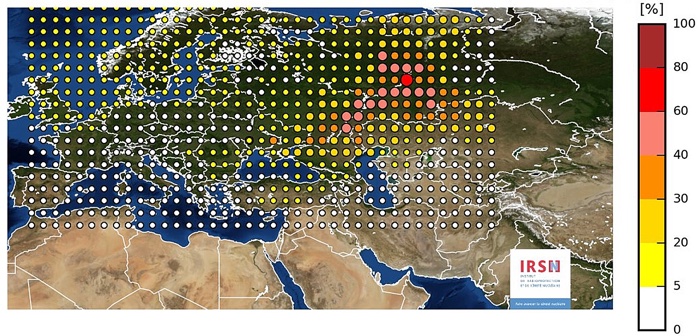

(IRSN)

(IRSN)

While the radiation spike is at its strongest in the Chelyabinsk region close to the border with Kazakhstan, the IRNS investigation – which suggested "the most plausible zone of release lies between the Volga and the Urals" inside Russia – shows the radioactive cloud actually blankets most of Europe.

The good news though is that the radiation cloud is expected to be harmless, with even these dramatically heightened levels of ruthenium–106 said to be of "no consequence for human health and for the environment".

"It is important to place this in context," explains medical physicist Malcolm Sperrin from Oxford University Hospitals in the UK.

"Ruthenium is very rare and hence its presence may suggest that an event of some nature has occurred. That being said, the natural abundance is so low that even a factor of 900 up on natural levels is still very low."

Nonetheless, the IRSN concluded that if the accidental release of this much ruthenium–106 had occurred on French soil, evacuations of the immediate area up to a few kilometres around the origin point would have taken place – so it's still a significant event that should have been treated with caution.

Ruthenium–106 is so rare that it doesn't naturally occur, and it's thought that the material may have been released due to an unreported accident at a nuclear fuel treatment site, or at a centre for radioactive medicine.

A more dangerous accident at a nuclear reactor is unlikely, because such an incident would have probably released additional radioactive elements, not just ruthenium–106.

"[T]he fact that the isotope decay appears to have been measured in isolation, rather than with the usual cocktail of other fission fragment signatures suggests a leak from a fuel/reprocessing plant or somewhere they are separating the Ru, possibly for use as a medical radiopharmaceutical/diagnostic material," says nuclear physicist Paddy Regan from the University of Surrey in the UK.

"If it was a reactor leak or nuclear explosion, other radioisotopes would also be present in the 'plume' and from the reports, they are not."

For its part, Russia is still claiming it didn't produce the surge, suggesting high levels of radiation above Italy, Romania, and Ukraine could mean those countries were responsible.

"The published data is not sufficient to establish the location of the pollution source," said Roshydromet head Maxim Yakovenko.

But the fact that Roshydromet itself detected the radiation cloud using two monitoring stations surrounding the Mayak nuclear facility – one of the largest plants in Russia – is leading others to question those claims.

After all, in 1957, Mayak was the site of the third-most serious nuclear accident ever recorded – the Kyshtym disaster, ranked behind only Fukushima and Chernobyl.

The event dispersed radioactive particles over a region covering approximately 52,000 square kilometres (20,000 square miles), but Soviet officials kept the accident a secret for almost two decades.

This time around, Mayak authorities have similarly denied being responsible for the leak, and Rosatom, the state-run body that oversees Russia's nuclear industry, also says there's nothing to see here.

"Rosatom categorically confirms there have been no unreported accidents or reportable events on any of its nuclear sites," the company told The New York Times.

"The highest concentrations are in areas outside Russia."