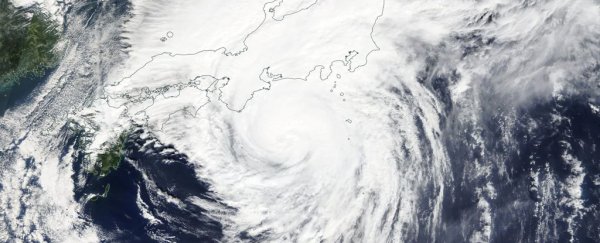

Typhoon Hagibis proved to be extraordinarily devastating for northern Japan when it struck this weekend, unleashing more than three feet of rain in just 24 hours in some locations, causing widespread flash flooding as well as river flooding. The storm has killed at least 58, according to the Japanese public broadcaster NHK.

In addition, high winds lashed Tokyo and Tokyo Bay, along with pounding surf and storm surge flooding as the storm, once a Category 5 behemoth, barreled across Honshu as the equivalent of a Category 2 and then a Category 1-equivalent storm.

One reason the storm caused such severe impacts is that the inner core of the typhoon, with its heaviest rains and highest winds, remained intact as it swept across Tokyo and dumped heavy rains across northeastern Japan as well.

According to reporting from The Washington Post's Simon Denyer, by Sunday, more than 20 rivers in central and northeastern Japan had burst their banks, flooding more than 1,000 homes in cities, towns and villages.

Numerous levees failed, and at one point, the government advised nearly 8 million people to evacuate, Denyer reported.

Severe flooding occurred in Nagano, Japan, the site of the 1998 Winter Olympics, where waters from the overflowing Chikuma River damaged a fleet of high-speed bullet trains that had been parked in a maintenance rail depot.

Storm track, intensity were key factors

Japan typically sees impacts from between five and six typhoons per year, though not all of these make direct landfall. Even among these, however, Typhoon Hagibis stands out for its track and the amount of rainfall it delivered to highly populated areas in a short period.

Frequently, typhoons affect the southwestern reaches of Japan first, and weaken to windswept rainstorms by the time they hit Tokyo. However, Typhoon Hagibis didn't travel over land for a long distance, and therefore was more damaging.

Instead, the eye of the storm came ashore close to 7 pm local time on Saturday on the Izu Peninsula, about 80 miles (129 kilometres) southwest of Tokyo. This track enabled Typhoon Hagibis to continue to tap into energy from the oceans and weaken at a slower rate than other storms do when they hit Japan.

In addition, the storm had begun to interact with the high winds at upper levels of the atmosphere known as the jet stream, which expanded the reach of its heavy rains and broadened its wind field so tropical storm force winds extended across much of Honshu.

The storm made landfall Saturday as it made a turn from moving north-northwestward to the northeast. It then crossed directly over the capital city of 9.3 million and swirled northward, with 8.23 inches (21 centimetres) of rain falling in Tokyo itself and more than three feet in higher elevations to the west of the city. Sustained winds at hurricane force affected downtown Tokyo, with a gust to 98 mph (158 km/hr) recorded at Haneda Airport.

In Hakone, in Kanagawa Prefecture, 37.1 inches (94 centimetres) of rain fell in 24 hours on Saturday, setting a record for that location, according to the Japan Meteorological Agency. In addition, 27 inches (69 centimetres) fell in heavily forested Shizuoka Prefecture southwest of Tokyo. In higher elevations just west of downtown Tokyo, 23.6 inches (60 centimetres) of rain fell, which was also a record.

Some of the rains fell ahead of the storm, beginning Friday as warm and moist air moved into Japan from the southeast, with clouds from the typhoon covering nearly the entire Japanese archipelago. As the tropical air collided with higher elevations the air was forced to rise, cool and condense in a process known as orographic lift, causing a deluge that resulted in mudslides and sent rivers bursting over their banks.

As the core of the storm pulled away from Tokyo on Sunday, it dumped heavy rains across Toshigi as well as Fukushima Prefecture. Floodwaters there have raised concerns about radioactive contamination following the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster.

Typhoon Hagibis will go down in Japanese history as a multibillion dollar disaster.

The storm's widespread impacts and high death toll are unusual for Japan, since the country is one of the best-prepared in the world for natural disasters given that it faces risks from earthquakes and associated tsunamis, volcanoes and other natural and human-influenced hazards, from heat waves in the summer to wintertime blizzards in its far northern areas.

Japan can expect more high-impact storms like Hagibis

Climate studies suggest the Japanese archipelago could see more frequent and stronger typhoons in the future, due in large part to warming seas as a result of human-caused global warming. There is evidence showing tropical cyclones in the Northwest Pacific Ocean Basin are reaching their maximum intensities farther north than they used to, a trend some scientists attribute in part to climate change.

This could send more intense storms into areas that typically see weaker storms, such as Honshu and other parts of northern and northeastern Japan.

One trend that is especially clear is damage costs from typhoons in Japan are escalating, with three of the top 10 most expensive Japanese typhoons since 1950 occurring in the past two years alone. Typhoon Faxai, which affected Tokyo in early September, is on that list.

Typhoon Hagibis is extremely likely to increase this number to four.

2019 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.