From mobile phones to microwave ovens, the modern world virtually glows with high-frequency electromagnetic radiation (EMF).

Many still reserve judgement on just how safe these kinds of energy waves are, but a sensitive new epidemiological study calls that hesitation into question, finding no reason to believe any brain tumours have been caused by EMF exposure.

Research led by the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal) in Spain has provided the most detailed analysis yet on the relationship between non-ionising radiation and brain cancers.

Electromagnetic radiation includes the kind of visible light waves emitted by everything from light bulbs to the Sun. Our eyes typically respond to light waves with a frequency between 430 and 770 terahertz.

Ultraviolet light near the higher end of that spectrum has been shown to damage our DNA, increasing the risk of skin cancer. More energetic waves, like X-rays and gamma rays, pose even more serious health risks.

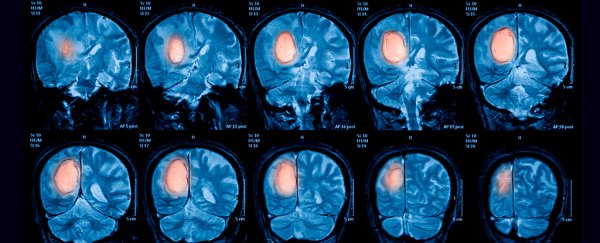

But in recent years, there's also been a concern that significant exposure to far gentler waves within a range of just a few kilohertz could penetrate the body and also cause health problems, including the aggressive neurological cancer glioblastoma.

Seven years ago, the World Health Organisation's International Agency for Research on Cancer evaluated the state of research on the topic and came to the conclusion there was enough reason to classify radiofrequency EMF as a possible carcinogen.

This isn't to say there's strong evidence of a relationship. Or much evidence at all.

But given the scale of the possible impact and the fact that radiofrequency EMF is so ubiquitous in our technology-soaked landscape, the WHO felt inclined to err on the side of caution.

The problem is that brain tumours aren't exactly the most common of cancers to begin with. Measuring a person's history of EMF exposure with any real precision in today's world is also a nightmare. So definitively linking the two isn't a walk in the park.

For this study, researchers dug into the existing scientific literature to come up with a matrix for estimating the amount of intermediate (3 kilohertz to 10 megahertz) radiation and radiofrequency (10 megahertz to 300 gigahertz) radiation subjects were exposed to in their homes and workplaces.

They used this source-exposure matrix to sort data from a study called INTERPHONE, which analysed primary brain cancers and mobile phone use, comparing roughly 4,000 cases of glioma and meningioma with more than 5,000 controls.

The individuals making up the study came from seven different countries and worked in a range of careers, including high exposure fields such as medical diagnostics, telecommunications, and radar engineering.

Such a controlled level of case-study detail on so many people is unprecedented as far as health studies on EMF exposure go.

"This is the largest study of brain tumours and occupational high-frequency EMF exposure to date", says the study's senior author Elisabeth Cardis.

Once the statistics were calculated, there was no sign of a correlation between having your head exposed to significant amounts of high-frequency EMF and primary brain tumours.

But unfortunately we can't close the book on this one yet.

In spite of the scale of the analysis, only one in ten of the participants dealt with relatively large exposures to EMF in a radiofrequency range, and only one in a hundred to intermediate frequencies.

In short, the scarcity of those exposed participants across the study leaves little room for various types of statistical sorting, and as useful as the source-exposure matrix is, it still relied on estimates that could have underestimated risk results.

There was also a subtle sign of a trend among individuals exposed to high frequency EMF within the past decade.

"Although we did not find a positive association, the fact that we observed indication of an increased risk in the group with most recent radiofrequency exposure deserves further investigation," says the study's first author, Javier Vila.

Taken all together, the results indicate we shouldn't worry for now, but we do need to focus future efforts on making sharper tools to analyse any hypothetical risk.

There's also a need to tease apart specific features of potential risks, perhaps investigating the roles of different chemical reactions to EMF.

For most of us, it's all business as usual. There's still a lot more to investigate, but for now, you can consider your head is safe from the unseen radiance of our techno-rich modern world.

This research was published in Environment International.