If you travel far enough away from the Sun, the Solar System becomes a lot more populated.

Out past the orbit of Neptune lies the Kuiper Belt, a vast, ring-shaped field of icy rocks. This is where Pluto resides, and Arrokoth, and countless other small objects in the cold and the dark.

These are known as Kuiper Belt objects or KBOs, and astronomers have just found hints of an unexpected rise in their density, between 70 and 90 astronomical units from the Sun, separated by a large, practically empty gap between it and an inner population of KBOs closer to the Sun.

It seems, almost, like there are two Kuiper Belts, or at least two components – something nobody was expecting to find.

"If this is confirmed, it would be a major discovery," says planetary scientist Fumi Yoshida of the University of Occupational and Environmental Health Sciences and Chiba Institute of Technology in Japan.

"The primordial solar nebula was much larger than previously thought, and this may have implications for studying the planet formation process in our Solar System."

The objects in the Kuiper Belt are thought to represent the most pristine material our Solar System contains.

The belt itself extends from the orbit of Neptune, around 30 astronomical units from the Sun (an astronomical unit is the average distance between Earth and the Sun), out to about 50 astronomical units from the Sun.

This distance from the Sun means that anything within the Kuiper Belt is only minimally affected by solar radiation, which, in turn, means that KBOs likely remain pretty much unchanged since the Solar System was born, some 4.6 billion years ago.

These objects are ancient remnants of the cloud of material, known as the solar nebula, from which the Sun and planets formed.

The New Horizons spacecraft has been heading out deeper into the Solar System since its flyby of Pluto in 2015; at time of writing, the spacecraft is nearly 60 astronomical units from the Sun and counting.

To support its ongoing exploration of the outer Solar System, astronomers here on Earth have been conducting observations of the Kuiper Belt using the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan's Subaru Telescope in Hawai'i.

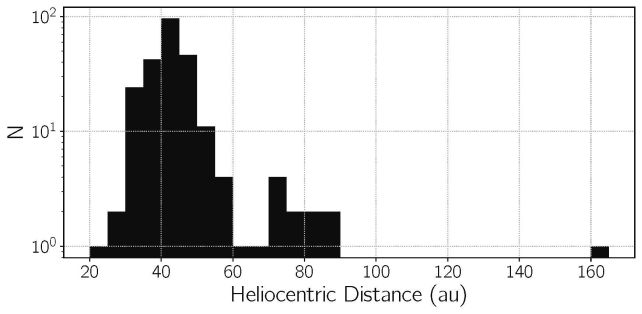

To date, the Subaru observations have revealed 263 new KBOs, but a large, international team of astronomers led by Wesley Fraser of the National Research Council of Canada has found that 11 of those objects are much, much farther than we thought the Kuiper Belt ended – out in the region past 70 astronomical units.

From the number of these objects spotted, the researchers were able to extrapolate the density of the outer Kuiper Belt ring. It would be lower than the inner population, but high enough to constitute a new structure.

In the region between 55 and 70 astronomical units, however, next to nothing has been found. This might sound strange, but a gap of this kind is a feature we've seen in other forming planetary systems, and it brings the Solar System more in line with what we've found elsewhere in the galaxy.

"Our Solar System's Kuiper Belt long appeared to be very small in comparison with many other planetary systems, but our results suggest that idea might just have arisen due to an observational bias," Fraser explains.

"So maybe, if this result is confirmed, our Kuiper Belt isn't all that small and unusual after all compared to those around other stars."

A lot of our observations of the Milky Way galaxy suggest that our Solar System is unusual in many ways. Since the Solar System is the only known planetary system to host life, these oddities could be contributing factors to the Solar System's habitability.

But our technology for observing space has limitations that could result in significant observation biases, suggesting peculiarities that don't actually exist. If the new observations of the Kuiper Belt are confirmed, we have just ruled out one of those peculiarities – an unusually small solar nebula.

In order to shed more light on the discovery, observations continue in order to track the orbits of the 11 distant objects.

"This is a groundbreaking discovery revealing something unexpected, new, and exciting in the distant reaches of the Solar System," says New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute.

"This discovery probably would not have been possible without the world class capabilities of Subaru observatory."

The research has been accepted into The Planetary Science Journal and is available on arXiv.