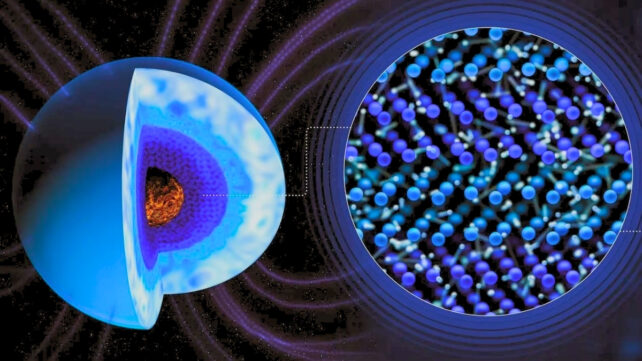

Inside the cores of ice giant planets, the pressure and temperature are so extreme that the water residing there transitions into a phase completely unfamiliar under natural conditions on Earth.

Known as 'superionic water', this form of water is a type of ice. However, unlike regular ice, it's actually hot, and also black.

For decades, scientists thought that the superionic water in the core of Neptune and Uranus was responsible for the wild, unaligned magnetic fields that the Voyager 2 spacecraft saw when passing them.

Related: Ice in Space Could Do Something We Thought Was Impossible

A series of experiments described in a paper published in Nature Communications by Leon Andriambariarijaona and his co-authors at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and the Sorbonne provide experimental evidence of why exactly the ice causes these weird magnetic fields – because it is far messier than anyone expected.

In school, most students are taught about the four phases of matter: Solid, liquid, gas, and plasma. But, at extremely high pressures and temperatures, water can exist in a superionic phase that, while it looks like a solid, is actually a form of crystal lattice. That lattice is formed by oxygen atoms, whereas hydrogen atoms flow freely across the lattice, conducting electricity as they go.

Scientists have long theorized that the lattice of oxygen atoms in superionic water formed a 'perfect' crystal, with atoms either at the center of a cube – a configuration known as body-centered cubic (BCC) – or atoms on the faces of the cube (face-centered cubic). Both of which provide the nice, cleanly defined edges scientists expect to see in a crystal structure.

But those nice crystal lattices didn't sit well with the lumpy, chaotic magnetic field Voyager 2 saw when it passed by our own ice giants. So scientists decided they needed to experimentally test this unique form of water to see if the lattice theory was correct.

To do so, they first had to make superionic water itself, which is no easy feat. It only exists at extremely high temperatures and pressures, and will immediately revert to other, more stable forms of water if either environmental variable is lowered.

Getting pressures that high requires a specialized tool known as a diamond anvil. Or, more specifically, two of them. Pushing a water sample between two anvils made from the hardest substance in the Universe allowed the experimenters to raise the pressure to 1.8 million atmospheres.

They then blasted the sample with pulsed laser light to heat it to around 2500 Kelvin. At that point, they had successfully created a sample of superionic water.

But, as soon as they lowered the pressure or the temperature, the crystal structure would disintegrate. So, within a few trillionths of a second after they reached those conditions, they blasted the sample with X-rays.

X-ray diffraction is a common practice in studying crystal structures. Essentially, it's a way of taking high-speed pictures of atomic positions. But when the researchers analyzed the resulting data, they realized their results didn't align well with the theory.

The lattice itself appeared to be a mix of blurred lines, where different layers of the structure were FCC, and some were actually a completely different structure known as hexagonal close-packed (HCP).

When the authors first ran their experiment in California, this messy data was so confusing that it prompted them to chalk it up to some sort of environmental error. This prompted them to enlist help from another linear accelerator in Germany to eliminate that potential source of noise.

When the results from the experiments in Germany came back the same, they realized they were seeing the real, messy truth rather than an artifact of their environment.

As they continued to experiment with different pressures and temperatures, the researchers also realized that some overlapping lattices appeared as pressure grew. This contradicted the theory that there was a very clear transition line where the lattice structure would snap between one structure and another.

Ultimately, this all suggests superionic water is a very complicated material. And those complications help explain what could be happening with wonky magnetic fields of Neptune and Uranus.

Just to be clear, running an experiment where these materials only exist for a few femtoseconds is not a perfect recreation of the interiors of the ice giant planets. Maybe over time, the crystal structure settles into a more rigid pattern. Or maybe the chaos that the experiments saw continues in random ways all throughout the Ice Giants themselves.

While we'll never see this type of water naturally on Earth, the fact that it makes up the interior of Ice Giant planets means this form of ice might actually be the most abundant type of water in the galaxy.

Ice Giants make up a significant fraction of known exoplanets, though that might simply be because of their size and orbit, both of which are easy to pick out using current exoplanet hunting methods, rather than their actual proportions of existing exoplanets.

Either way, knowing that water – the stuff that is needed for life on Earth – has so many varieties in so many different places, is at least a fun scientific fact.

This article was originally published by Universe Today. Read the original article.