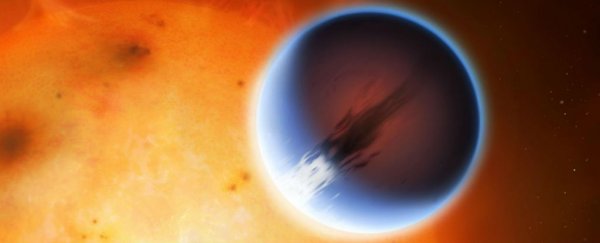

Astronomers have found a planet so dark it absorbs almost all light that hits it through a dense layer of haze. Its discoverers have compared it to charcoal, and it's one of the darkest planets ever discovered.

The planet in question, named WASP-104b, is a type of planet known as a hot Jupiter.

Hot Jupiters are pretty strange. They're gas giants with masses in the range of Jupiter, but they're extremely close to their stars, usually orbiting in a period of less than 10 days.

Because of this proximity, these planets are also extremely hot. They're not a rarity, but they do have a set of characteristics that make them a bit of a mystery.

One of these is that hot Jupiters are relatively dark. Most of them reflect about 40 percent of the starlight that reaches them.

But occasionally, astronomers will find one that's a lot darker - like WASP-12b, which last year was discovered to absorb at least 94 percent of the light that hits it.

WASP-104b is even darker. According to researchers at Keele University in the UK, it absorbs more than 97 to 99 percent of light.

"From all the dark planets I could find in the literature, this is top five-ish," lead researcher and astrophysicist Teo Mocnik told New Scientist. "I think top three."

The reason for this darkness probably has to do with the planet's close proximity to its star, a yellow dwarf around 466 light-years away from us, in the constellation Leo.

Like most hot Jupiters, WASP-104b is tidally locked, meaning one side always faces its host star.

So WASP-104b has a permanent day side and permanent night side - and it's so close to the star, a distance of around 4.3 million kilometres (2.6 million miles), that it takes just 1.75 days to complete a full orbit.

This means that the day side is so hot clouds can't form, and clouds are typically very reflective, as Venus demonstrates. It's also too hot for ice - the kind of surface that makes the moon Enceladus so bright.

Instead, WASP-104b has a thick, hazy atmosphere, probably containing atomic sodium and potassium, which absorb light in the visible spectrum, making the planet very dark on the day side.

On the night side, away from the starlight, clouds may form - but that side never sees daylight, so there's no light nearby for it to reflect.

Even though they're darker than normal, hot Jupiters are no harder to detect than normal planets. They're all too far away for us to detect their planetshine, or to distinguish from the much brighter stars they orbit.

Instead, we detect them by observing a regular, periodic dimming of the star's normal light levels as the planet moves in front of them. This is called the transit method, and it's how NASA's planet hunter Kepler operates - so it's pretty effective.

But because they're so big and so close to their stars, hot Jupiters can also be detected using the radial velocity method. This is when a star wobbles ever so slightly, tugged into a small circular movement by the gravitational pull exerted by the body orbiting it.

They're also not really matte black, like charcoal, pitch, or Vantablack - that comparison is for reflectiveness, not emitted light. Because of their extreme heat, they should glow - a deep, bruise-like purple or a dull molten red. Imagine an ember glowing in a firepit.

The darkest hot Jupiter that we know of to date is a planet called TrES-2b, which reflects as little as 0.1 percent of the light that hits it. But as investigations continue, it could be that WASP-104b has real potential to challenge for that title.

The team's research has been published in the pre-print resource arXiv, and is awaiting peer review.