The Sun starts to turn black. Land sinks into sea. Steam spurts up. Flame flies high against heaven itself.

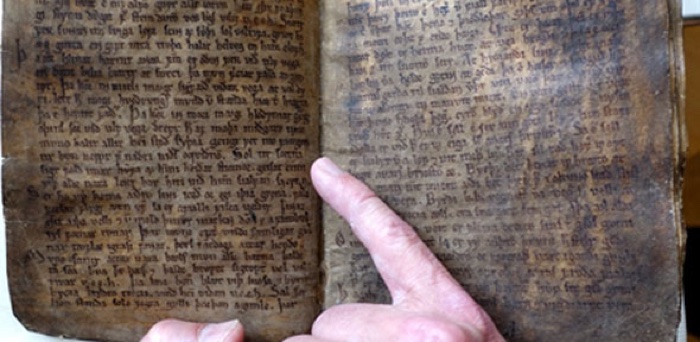

These cataclysmic words come from Völuspá – a famed poem from Iceland's medieval past, telling of the fabled destiny and destruction of the old Norse gods, before the world was born anew. Only, as scientists have just discovered, these dark words may not be a fable after all.

An analysis of ancient ice cores extracted from Greenland has for the first time accurately dated Iceland's largest volcanic eruption of last two millennia, the Eldgjá lava flood – a colossal outburst that immersed the island in 20 cubic kilometres of lava, only decades after it was first settled by Vikings and Celts.

According to researchers led by the University of Cambridge, this devastating episode commenced around the spring of the year 939 and continued through until the autumn of 940 – just 20 years or so before Völuspá, 'The Prophecy of the Seeress', is estimated to have been written.

The implication of this coincidence? Arguably, Völuspá isn't just one of our most primary sources for everything we know about Thor, Loki, Odin and the rest of their Asgardian ilk.

Hypothetically, the timing suggests it could also be a historical chronicle of Eldgjá and its aftermath – a volcanic episode so awesome and terrible it may have helped bring about the end of the Norse gods in medieval minds, accompanying the rise and embrace of Christianity in Iceland long ago.

"With a firm date for the eruption, many entries in medieval chronicles snap into place as likely consequences – sightings in Europe of an extraordinary atmospheric haze; severe winters; and cold summers, poor harvests; and food shortages," says volcanologist Clive Oppenheimer.

"But most striking is the almost eyewitness style in which the eruption is depicted in Völuspá. The poem's interpretation as a prophecy of the end of the pagan gods and their replacement by the one, singular god, suggests that memories of this terrible volcanic eruption were purposefully provoked to stimulate the Christianisation of Iceland."

If they're right, the Seeress's Prophecy contains the only direct references to the fire and flame of Eldgjá's explosion.

(University of Cambridge)

(University of Cambridge)

While medieval documents from Germany, Iraq, and China detail the famine and drought that resulted under the ensuing ash cloud, on-the-spot accounts of the lava flow itself are understandably absent from Iceland's historical record.

"The effects of the Eldgjá eruption must have been devastating for the young colony on Iceland – very likely, land was abandoned and famine severe," says one of the team, medieval literature historian Andy Orchard from the University of Oxford.

If the hypothesis is correct, the researchers say the eruption would have taken place in the first two or three generations of Norse settlers coming to Iceland – a rude welcome for this early wave of migrants, greeted with fire, smoke, and destruction – quite possibly a deadly catalyst for divine reinvention:

"[The wolf] is filled with the life-blood of doomed men, reddens the powers' dwellings with ruddy gore; the sun-beams turn black the following summers, weather all woeful: do you know yet, or what?"

"The Sun starts to turn black, land sinks into sea; the bright stars scatter from the sky. Steam spurts up with what nourishes life, flame flies high against heaven itself."

The findings are reported in Climatic Change.