The grinding together of rocks thanks to quakes on Mars could produce sufficient levels of hydrogen to support life, researchers have found.

The hypothesis is based solely on rocks from the Outer Hebrides of Scotland - a pretty long way from Mars - but the team thinks the same process could occur on any rocky planet with seismic activity, thanks to the way hydrogen is retained by rock formations.

"Previous work has suggested that hydrogen is produced during earthquakes when rocks fracture and grind together," says one of the team, Sean McMahon, a geologist at Yale University.

"Our measurements suggest that enough hydrogen is produced to support the growth of microorganisms around active faults."

When earthquakes cause rocks to bash against each other, hydrogen is one of several compounds released - but it can also be trapped.

McMahon and his team found that, after the fracturing of an earthquake, small pockets of hydrogen are created and stored inside fine-grained rocks called pseudotachylites.

Pseudotachylites are known to form through what's called frictional melting during seismic activity, giving them the nickname, fossil earthquakes.

While human beings depend upon oxygen to survive on Earth, it's possible that other forms of life could live off this hydrogen under the Martian surface, the team speculates.

Of course, until we can conduct further investigations on Mars, the researchers' idea will have to remain a hypothesis for now.

But one of the purposes of NASA's next probe mission in 2018 is to measure seismic activity on the planet, and based on the best estimates we have, even tiny 'Marsquakes' would be sufficient to generate the right levels of hydrogen for life.

"Mars is not very seismically active, but our work shows that Marsquakes could produce enough hydrogen to support small populations of microorganisms, at least for short periods of time," says McMahon.

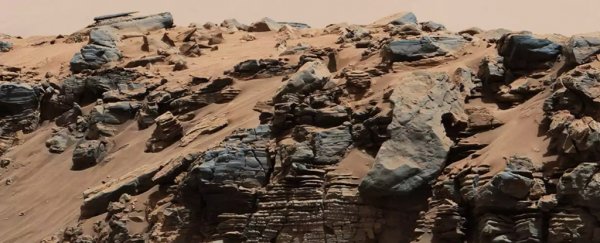

Pseudotachylites from the British Isles, packing hydrogen. Credit: Yale University

Pseudotachylites from the British Isles, packing hydrogen. Credit: Yale University

To be clear, there's currently no solid evidence just yet that hydrogen exists at any significant level on Mars, where more than 95 percent of the atmosphere is made up of carbon dioxide. But probes sent to the planet have detected traces of hydrogen leaking away from Mars as its water vapour breaks apart.

If we can find more evidence of hydrogen on the Red Planet, it could point us to signs of past or current life below the surface.

And it might also aid the first human settlers, as hydrogen can be combined with carbon dioxide (which is abundant on Mars) to produce oxygen - a process that's already in place on the International Space Station.

For those investigating the best ways of terraforming Mars, hydrogen-packed rocks could be of particular interest, although from what we know based on this new study, it would only exist in very small amounts - just enough for the tiniest of organisms.

But still, the findings suggest that Mars could be more chemically rich than we originally thought - and that's encouraging news if we eventually want to live there.

The research is published in Astrobiology.