Before a new drug or medical treatment can be let loose on human beings, it has to go through a rigorous set of tests to make sure it's safe – tests that unfortunately often involve animals.

But the US government has been pushing researchers to find more humane alternatives to animal testing, whether it's highly efficient robots or advanced computer algorithms.

One of the most ambitious options is to replace animal models with a 'human body on a chip' – something that has the potential not just to match the usefulness of animal testing, but actually exceed it. And scientists are closer than ever to actually creating one.

One such effort to develop organ-mimicking computer chips is currently being led by bioengineer Linda Griffith from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Griffith's Human Physiome on a Chip program has received millions in funding from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the National Institutes of Health, as Sarah Zhang at Wired reports.

Simulating the complexities of the human body is no easy task, of course, but progress in software and electronics means we're closer than ever to getting it right. These organs-on-chips are likely to first appear in scenarios where animal testing doesn't quite provide the results that scientists need.

Take immunotherapy cancer treatments, for example. They're designed to target specific proteins on human immune cells, like putting together two pieces of a jigsaw, and tests on animals or even on human cells in a petri dish are poor substitutes.

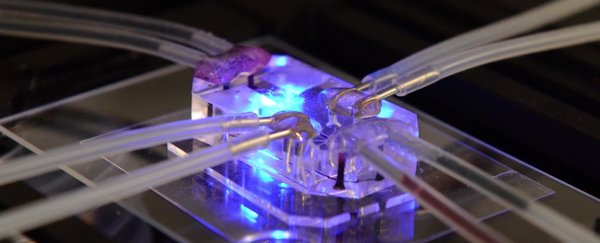

These treatments need to be tested in relation to the whole human body, so Griffith has built up a system with seven 'organs' on a chip, and is now working on expanding it to 10.

"The modules are designed to mimic the functions of specific organ systems representing a broad spectrum of human tissues, including the circulatory, endocrine, gastrointestinal, immune, integumentary, musculoskeletal, nervous, reproductive, respiratory and urinary systems," explains the Human Physiome on a Chip project.

Most organ chips are made from synthetic materials such as polymers, which are often made transparent so they can be viewed through a microscope.

When cultured human cells are added to the artificial structures, they begin to behave as if they were actually in the body, opening up a valuable resource for drug and treatment testing. A tiny circulatory system of microfluidic tubes keeps everything flowing.

Projects similar to the one at MIT are ongoing elsewhere too, with another DARPA-funded Organs-on-Chips program being developed at the Wyss Institute at Harvard University. The model created by the researchers at the Wyss Institute is so cleverly constructed it won a design award last year.

Other researchers are also working on alternatives to animal testing using other means – ranging from lab-grown mini-brains developed from human cells that could replace animals in drugs testing, through to new mathematical models that can predict the effect of chemicals on human skin, thereby negating the need for lab testing on animals.

While we're still likely to be a long way from fully replacing animal experiments with organs-on-chips, the new research looks highly promising, and it's something everyone wants to see happen: scientists, regulators, and drug companies alike – not to mention the millions of animals annually subjected to testing in the US.

This transition has been a long time coming, and thanks to science, we're finally seeing it start to happen.