The coffee in the break room at work could contain high levels of substances that elevate levels of 'bad' cholesterol in your blood – but there's a simple way to reduce them.

Diterpenes are compounds made by plants that have a variety of effects on the human body. Two of them – cafestol and kahweol – have been linked to increased levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. High levels of these compounds have been found in coffee, but it seems to depend on how you extract it.

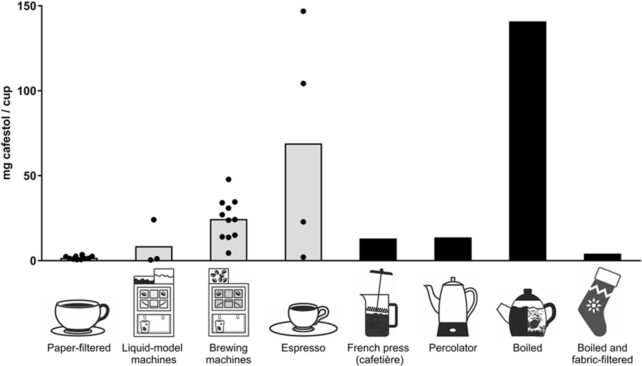

Swedish researchers measured the levels of diterpenes in coffee made by a range of common coffee machines and brewing techniques. They found that boiling a big pot of coffee is the worst offender, but you can easily offset those levels by filtering it.

Coffee machines commonly found in workplaces around the world also produced cups of joe with relatively high diterpene levels.

"We studied 14 coffee machines and could see that the levels of these substances are much higher in coffee from these machines than from regular drip-filter coffee makers," says David Iggman, a clinical nutritionist at Uppsala University.

"From this we infer that the filtering process is crucial for the presence of these cholesterol-elevating substances in coffee."

The team calculated the benefits for a person drinking three cups of coffee a day, five days a week. Swapping the machine coffee for a nice paper-filtered java could reduce LDL cholesterol by enough to cut the relative risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease by 13 percent over 5 years, and 36 percent over 40 years.

The researchers collected samples from 11 machines that brewed coffee from grinds mixed with hot water and passed through a metal filter, and from a further three that mixed a liquid coffee concentrate with hot water without filtration.

For comparison, the team also brewed coffee themselves using a range of methods, including drip-brew, percolator, French press, and boiled coffee. Samples from each method and machine were then frozen for storage and transport, before being analyzed for diterpene concentration. In addition, the team collected four espresso samples from three cafeterias and a workplace.

The team found that manual methods of brewing coffee generally resulted in lower diterpene levels than grabbing a cup from a machine, whether it be a brewing machine, a liquid-model machine, or a traditional espresso maker.

At a glance, espresso seemed to be the worst way to make coffee, with a median cafestol level of around 1,060 mg/L. But there were only four samples analyzed and their levels varied wildly, from 35.6 to a staggering 2,446.7 mg/L. As such, it's hard to pull much meaning out of that.

Coffee from liquid and brewing machine models had a median cafestol concentration of 174 milligrams per liter, and 135 mg/L of kahweol. French presses produced coffees with moderate diterpene levels, coming in under 90 mg/L for cafestol and under 70 mg/L for kahweol, while percolators had similar readings.

The best option seemed to be paper-filtered drip brews, clocking a median of just 11.5 mg/L of cafestol and 8.2 mg/L for kahweol.

The exception was boiled coffee, a typically unfiltered method that's common in countries such as Sweden. Getting your caffeine fix this way resulted in a massive mean concentration of just under 940 mg/L of cafestol and nearly 680 mg/L of kahweol.

Thankfully, it's easy to slash those levels. When the researchers filtered their boiled coffee through fabric, concentrations dropped to just 28 mg/L for cafestol and 21 mg/L for kahweol. They used a sock for some reason, but any cloth or paper filter should do the trick.

The team also acknowledges that the study has major limitations, including small sample sizes and variables that went unaccounted for, like filter pore size, water pressure, and temperature, and how the beans were roasted and ground.

The findings join a growing and often conflicting body of research into the health effects of coffee – and it's hard to know how it all fits together. Other studies, for instance, have found that drinking three or more cups of coffee per day could lower your risk of developing cardiometabolic diseases by 40 percent.

Regular coffee consumption has also been linked to lower risks of dementia, Parkinson's, and skin, mouth, and bowel cancer. It could offset the negative health effects of prolonged sitting, and even extend your life by years. But that could all depend on how many cups you down per day, what time you drink them – and now, how you brew it.

"Most of the coffee samples contained levels that could feasibly affect the levels of LDL cholesterol of people who drank the coffee, as well as their future risk of cardiovascular disease," says Iggman. "For people who drink a lot of coffee every day, it's clear that drip-filter coffee, or other well-filtered coffee, is preferable."

The research was published in the journal Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases.