NASA's Hubble space telescope has detected plasma balls roughly twice the size of Mars being ejected near a dying star at speeds so rapid, it would take them only 30 minutes to travel from Earth to the Moon.

This mysterious 'cannon fire' has been detected in the region once every 8.5 years for at least the past 400 years, but this is the first time it's ever been seen in action, and researchers think they might finally know where it's coming from.

Plasma is super-hot ionised gas, and the reason these blasts are so confusing for astronomers is that there's no way they can be coming from the dying star they originate near.

The star in question, called V Hydrae, is a bloated red giant that's 1,200 light-years away, and it's dying. It's already shed at least half of its mass into space in its final death throes, and is now exhausting the rest of its nuclear fuel as it burns out - hardly a likely source of super hot, giant blobs of charged gas.

But the new Hubble data provide researchers with some insight into the strange phenomenon, and it turns out that these plasma cannonballs might explain another space mystery - planetary nebulae.

Planetary nebulae aren't like regular nebula, which are the birthplace of stars. Instead, they're swirling rings of glowing gas that are expelled by dead or dying stars. Each one is unique, but no one has been able to explain how they form.

Now NASA researchers suggest that the cannonballs may play a key role.

"We knew this object had a high-speed outflow from previous data, but this is the first time we are seeing this process in action," said lead researcher Raghvendra Sahai, from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California.

"We suggest that these gaseous blobs produced during this late phase of a star's life help make the structures seen in planetary nebulae."

To figure this out, the team pointed the Hubble telescope at V Hydrae over an 11-year period, between 2002 and 2013.

This allowed them to capture the latest cannonball eruption back in 2011, using spectroscopy imaging to reveal information on the plasma's velocity, temperature, location, and motion.

They were able to show a whole string of the huge plasma balls erupting from the region, each with a temperature of more than 9,400 degrees Celsius (17,000 degrees Fahrenheit) - almost twice as hot as the surface of the Sun.

While the team monitored these news cannonballs, they also mapped the distribution of old plasma blobs fired out as long ago as 1986, some of which were already 60 billion km (37 billion miles) away from V Hydrae.

These plasma balls cool down and expand the further they get until they're no longer detectable by Hubble.

So where are they coming from? Based on all this new data, the NASA team modelled several scenarios, and the one that made the most sense is that the cannonballs are being launched by an unseen companion star that orbits close to V Hydrae every 8.5 years, but isn't seen by Hubble.

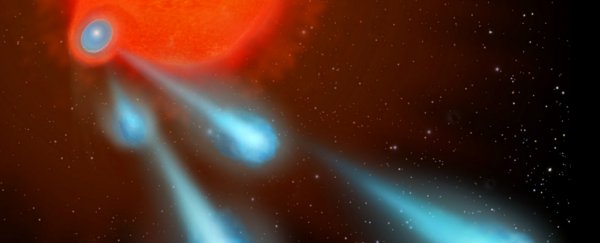

The model suggests that as the companion star enters V Hydrae's outer atmosphere, it gobbles up all the material that V Hydrae is shedding in its death throes, and this material then settles around the companion star as an accretion disk that shoots out balls of plasma.

The researchers have recreated what that would look like below. Step 1 is the two stars orbiting each other. Step 2 shows the companion star orbiting into the red giant's bloated atmosphere and sucking up its material into an accretion disk.

In steps 3 and 4, blobs of hot plasma are being ejected from this accretion disk. This happens every 8.5 years as the companion star orbits into V Hydrae's atmosphere.

Not only could this explain the strange balls, it could also explain how bloated dying stars turn into beautiful, glowing planetary nebulae within just 200 to 1,000 years - which is an astronomical blink of an eye.

Hubble has captured images of planetary nebulae with a range of knotty structures with them, which looked a lot like jets of material ejected from accretion discs. But red giants don't have accretion discs, so it never quite made sense. Now it's possible that the knotty structures are produced by hidden companion stars.

"This model provides the most plausible explanation," said Sahai.

Another surprise from the study was that the plasma balls aren't fired in the same direction every 8.5 years, it flip-flops slightly from side to side and back and forth, suggesting that there's a wobble in the accretion disk.

This wobble means that sometimes the cannonballs would be shot out in front of V Hydrae (from Hubble's perspective) and sometimes behind, and could explain why the star is obscured from view every 17 years.

"This discovery was quite surprising, but it is very pleasing as well because it helped explain some other mysterious things that had been observed about this star by others," said Sahai.

More research is needed to verify this new hypothesis, and figure out the ultimate fate of the potential companion star and V Hydrae. But NASA will be watching closely to see what happens as the red giant eventually turns into a beautiful planetary nebula. There are worse ways to go.

The research has been published in The Astrophysical Journal.