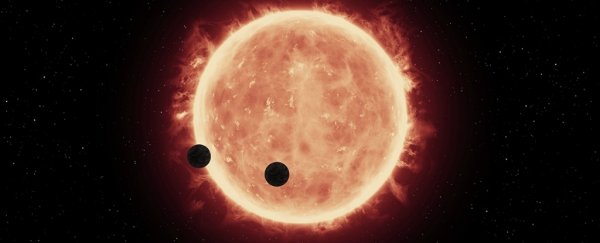

Astronomers working with NASA's Hubble Space Telescope have, for the first time, analysed the atmospheres of two Earth-sized exoplanets beyond our Solar System, concluding that they might be ideal for fostering life.

The findings suggest that the two exoplanets – TRAPPIST-1b and TRAPPIST-1c, which are around 40 light-years away – do not have hydrogen-based atmospheres, which the team says would make them inhospitable, as hydrogen-dense atmospheres usually lead to a devastating greenhouse effect.

"The lack of a smothering hydrogen-helium envelope increases the chances for habitability on these planets," team member Nikole Lewis, from the Space Telescope Science Institute in the US, said in a statement.

"If they had a significant hydrogen-helium envelope, there is no chance that either one of them could potentially support life because the dense atmosphere would act like a greenhouse."

The two exoplanets in the study were first discovered back in 2015 by the Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope (TRAPPIST), which is located at the ESA's La Silla Observatory in Chile. So far, researchers know that the planets orbit a star believed to be 500 million years old inside the constellation of Aquarius.

Since their discovery, astronomers have been excited to study the two planets because they might orbit inside the Goldilocks Zone – a distance that is not too far and not too close to a star, providing the ideal temperatures to support life.

"TRAPPIST-1b completes a circuit around its red dwarf star in 1.5 days and TRAPPIST-1c in 2.4 days. The planets are between 20 and 100 times closer to their star than the Earth is to the Sun," NASA officials explain.

As the star is so much weaker than our Sun, the scientists suggest that TRAPPIST-1c could lie within the habitable zone, with its moderate temperatures providing the right conditions for water to exist in liquid form.

The new atmospheric study took place on May 4 when both of the planets were in front of the star at the same time, an event known as a 'double-transit' that only happens once every two years. With both of the planets visible, the team was able to use spectroscopy to find clues as to what their atmospheres are made of.

While the exact chemical makeup is still unclear, the team says they were able to rule out that the atmospheres contain high levels of hydrogen and helium, which increases the chances that they might harbour life.

"These Earth-sized planets are the first worlds that astronomers can study in detail with current and planned telescopes to determine whether they are suitable for life," said team leader Julien de Wit, from MIT.

"Hubble has the facility to play the central atmospheric pre-screening role to tell astronomers which of these Earth-sized planets are prime candidates for more detailed study with the Webb telescope."

The team hopes that as more telescopes come online – such as the James Webb Space Telescope – they will have the ability to fully understand the composition of these exoplanets to determine how Earth-like they truly are.

"With more data, we could perhaps detect methane or see water features in the atmospheres, which would give us estimates of the depth of the atmospheres," said team member Hannah Wakeford, from NASA's Goddard Space Flight Centre.

This isn't the only study astronomers are excited about this week, though. On July 20, researchers working with NASA's Kepler telescope found a whopping 100 new exoplanets, with two of them possibly having the ability to support life.

The new study was recently published in the journal Nature.