Science can now confirm that your fifth grade teacher – the one who was always catching you out – might as well have had eyes in the back of their head.

While we can't establish any alleged mutant qualities, a new study has shown our brains happily cope with enough visual information to provide constant 360 degree perception.

Experiments conducted by engineers from Tohoku University in Japan recently put to the test the question of how far we can push the amount of information coming from our eyes in order to build a mental map of our surroundings.

It's pretty clear that our brain's visual hardware does an outstanding job given the limitations of the tools it has to work with.

Take your ridiculous eyes, for instance. Evolution has seen fit to grow the photoreceptor cells that make up the retina of vertebrates like us in such a way that they seem to point backward.

If the inside of your eyeball was a cinema, there'd be cables dangling in front of it. Go ask for your money back.

Granted, we do have great 3D perception providing a detailed sense of depth, but this in turn comes at a cost of a wider field of vision.

Add to this the fact that the patch of light sensitive cells responsible for collecting most of the information we focus on at any one moment is a little bigger than this comma, and you can see what we're dealing with.

To provide us with enough detail to help us move through the world, our visual system uses a number of tricks to patch together a reasonably accurate sense of our surroundings.

One of its talents is to constantly jiggle about in sharp movements called saccades, sweeping up visual clues that contribute to a spatial sense of our surroundings.

This ability to edit together a visual impression raises an interesting question, one which until now has had little evidence to work with – just how big can that mental picture of our immediate surrounds be?

Remembering landmarks through learning symbolic relationships of our surroundings is one way we build a mental picture of what we can't see.

But that wasn't what interested the researchers.

"Our interest is in the visual process, which is likely used to control action more directly and without conscious effort in comparison with conceptual representation," they write in their report.

To study this part of the process, the researchers hooked together six LCD monitors to create a 360 personal cinema for volunteer Tohoku University students to stand inside.

Each screen then displayed a layout of the letters T and L in six randomised positions, each rotated into an orientation that make things a little more confusing.

Half of the layouts were repeated in each trial, while the other half had letters that were mixed around.

Crucially, the volunteers didn't explicitly know this, so were left to hunt for a target T or L on each screen over successive trials.

It was expected that the repeated layouts would provide what's called a contextual cueing effect that would slowly help them find their targets in less time than in the shifting patterns.

Variations on the experiments were conducted using up to 29 volunteers, giving the researchers a bank of samples that they could analyse to determine how our brains build a visual model of our surroundings.

The results showed we quickly develop a detailed sense of what's behind us, providing a constant 360 degree model of our environment.

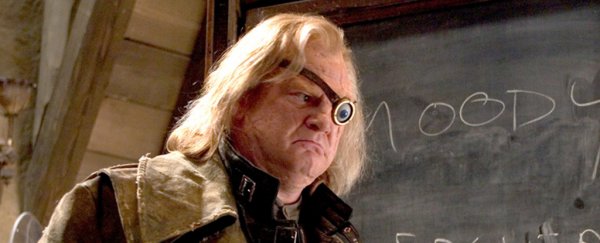

Harry Potter's 'Mad Eye Moody' probably didn't need that roving magical eyeball after all. His brain did a good enough job keeping watch over his back anyway.

This research was published in Scientific Reports.