Given half a chance, lions aren't above chewing on the occasional Homo sapien that might stray unguarded into their territory. Fortunately, few of the African big cats have ever made a habit of actively seeking out humans to dine upon.

There are exceptions, of course. One of the most notorious occurred in Kenya's Tsavo region in 1898, when two male lions spent months terrorizing workers building a railroad bridge across the Tsavo River.

The century-old teeth of these lions – long mythologized as 'man-eaters' – are now revealing new secrets, including not just whether they ate humans but also clues as to why.

Using recent advances in techniques for sequencing and analyzing old and degraded DNA, researchers from the US and Kenya investigated animal hairs stuck in the lions' teeth.

They report their findings in a new study, including specific animals the lions ate.

Insight like this might help us not only fact-check stories about the episode, but also better understand what could drive wild predators to behave so unusually.

The first reports of lion attacks began in March 1898, shortly after the arrival of Lt. Col. John Henry Patterson, a British army officer and engineer overseeing the project to connect the interiors of Kenya and Uganda with a railway.

The British had brought in thousands of workers to build the bridge, mostly from India, housing them in camps spanning several miles, Patterson wrote.

Patterson initially doubted reports of two workers abducted by lions, but was convinced weeks later when Ungan Singh, an Indian military officer accompanying him, suffered the same fate.

Patterson spent that night in a tree, promising to shoot the lion if it returned. He did hear "ominous roaring," he wrote, then a long silence, followed by "a great uproar and frenzied cries coming from another camp about half a mile away."

The next morning, he learned a lion had attacked another part of the camp.

Thus began a lengthy campaign by Patterson and others to kill the culprits: two large, maneless male lions. Maneless males are more common in some regions, including Tsavo, possibly due to the local climate or vegetation.

The attacks once abruptly stopped for a few months, Patterson notes, although "from time to time we heard of their depredations in other quarters."

When the lions finally returned, they seemed even bolder: Instead of attacking individually as before, they often entered camps together.

Patterson ended up killing both lions that December.

The lions' final death toll remains unclear; some estimates range as high as 135, though a 2001 study finds the numbers were likely to be closer to around 30 – a figure that, although far smaller, is by no means insignificant.

Patterson kept the lions' remains, eventually selling them to the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago in 1925.

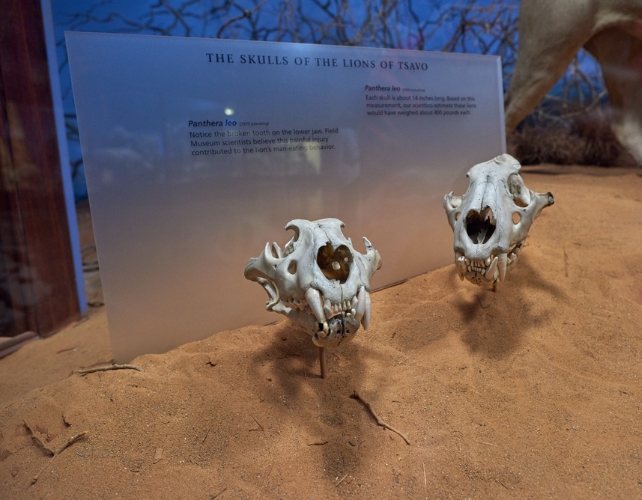

Decades later, when ecologist Thomas Gnoske, the museum's collections manager, found the lions' skulls in storage, he noticed hair fragments stuck in exposed tooth cavities.

Some scientists speculate the lions hunted humans precisely because of damaged teeth, which could have made it hard to subdue larger prey.

In any case, the damage seems to have preserved clues about the lions' diet. Gnoske and colleagues have now conducted an in-depth study of the hairs, including microscopic and genomic analyses.

First, they had to confirm the hairs' age, explains co-author Alida de Flamingh, a conservation biologist at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

"We look to see whether the DNA has these patterns that are typically found in ancient DNA," de Flamingh says.

Once the samples were verified, the authors homed in on mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). It's more plentiful in cells than nuclear DNA, and hair can also preserve mtDNA and limit contamination, which helps with older samples.

"And because the mitochondrial genome is much smaller than the nuclear genome, it's easier to reconstruct in potential prey species," de Flamingh adds.

The hairs weren't in great condition, but they still yielded usable mtDNA. Some hairs came from the lions themselves.

The rest originated mostly from an unsurprising mix of local ungulates – with one notable exception. The teeth of these infamous man-eaters did, in fact, contain human hair.

"Analysis of hair DNA identified giraffe, human, oryx, waterbuck, wildebeest and zebra as prey, and also identified hairs that originated from lions," de Flamingh, Gnoske, and team write.

The lions' mtDNA suggests they were brothers, as suspected. They had eaten at least two giraffes, according to the analysis, and a local zebra.

The team also created a database of mtDNA profiles for potential prey species occupying the lions' habitat in 1898.

Finding wildebeest mtDNA was odd, they note, since the nearest wildebeests back then lived some 50 miles away. But when Patterson reported an extended lull in attacks, maybe the lions were off hunting wildebeests.

It was also noteworthy to find just one buffalo hair, the authors add, and no buffalo mtDNA. "We know from what lions in Tsavo eat today that buffalo is the preferred prey," de Flamingh says.

That could hint at why these lions hunted people.

"Patterson kept a handwritten field journal during his time at Tsavo," says paleoanthropologist Julian Kerbis Peterhans of Roosevelt University and the Field Museum. "But he never recorded seeing buffalo or indigenous cattle in his journal."

Rinderpest, a viral disease of ungulates, had been introduced from India to Africa years earlier. It obliterated buffalo and cattle across the region in the 1890s, possibly forcing some lions to find new prey.

For this study, the researchers opted not to conduct further analysis of the human hairs to identify potential victims.

"There may be descendants still in the region today, and to practice responsible and ethical science, we are using community-based methods to extend the human aspects of the larger project," they write.

The study was published in Current Biology.