Isolated from its mother's body, a chicken embryo's only source of food is a golden-yellow dollop of nutrients known simply as yolk.

Sustained by the placenta, mammals like ourselves have no need for a personal snack-pack to keep us going. Still, within a week or so of fertilization, our developing bundles of cells spend precious resources making the sac yolk would go into.

By the end of the first trimester, the temporary organ has already begun to atrophy without ever holding a drop of food, until by 14 weeks it's no longer detectable.

Now a large team of researchers led by the Wellcome Sanger Institute in the UK has uncovered a good reason for holding onto this seemingly useless relic of our deep evolutionary past. A few good reasons, in fact.

"Mapping out how the yolk sac evolves during these first weeks of pregnancy is fundamental to the understanding of the development of the immune system," says dermatologist Muzlifah Haniffa, senior author of a recent study profiling the human yolk sac's tissues as part of the international Human Cell Atlas initiative.

"This is the first time that we show the multiple organ functions of the yolk sac – we've seen a relay from the yolk sac to the liver, to the bone marrow."

Investigations based on various model animals suggest our yolk sac is the source of our very first blood cells. Not just the oxygen-transporting red variety, but the white cells that serve as an immune response, which travel from the sac to the liver, and then later to the bones where they settle to help form marrow.

While this broad functionality seems clear, there have been few studies on human yolk sacs specifically, leaving questions on just how we might compare.

To better understand how these embryonic tissues operate specifically within our own species, researchers sequenced any strands of RNA being actively churned out by its cells and created a list of the materials being generated.

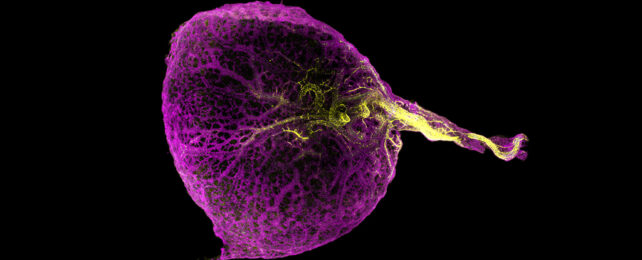

Combined with similar datasets, this reference library amassed from nearly 170,000 human yolk sac cells formed a highly detailed 'atlas' consisting of 15 broad categories of tissue types that not only produced blood cells, but contributed to a variety of important early functions.

With samples covering the period of development from four to eight weeks after conception, it was possible to form a timeline of activity, one that revealed this tiny blob of tissue has a critical role in the emergence of a broad range of systems.

As with most other animals, our yolk sac serves as an early producer of blood cells, clotting agents, and metabolic enzymes. Even without yolk present, the transient structure plays an important role in breaking down sugars and lipids, dealing with toxins, and fast-tracking the development and dispersal of immune cells.

Yet by unraveling the genetic processes down on a cellular level, the researchers identified significant differences in the cellular and biochemical pathways of human yolk sac tissues and those in typical lab models such as mice.

Knowing how the yolk sac directs key parts of our early development could inform future theories on disease, or improved processes of artificially growing tissues and organs.

"This is the first time that the yolk sac has been profiled at a single cell level, giving us an incredible amount of information on how this primary organ works in the first stages of human development," says bioinformatician and co-first author, Issac Goh.

"It has given us novel insights into the earliest blood and immune cells we make, building on the work uncovered in previous studies from the Human Cell Atlas. We did not know that the yolk sac had these functions until now."

This research was published in Science.