Homo naledi, a strange new species of human cousin found in South Africa two years ago, was unlike anything scientists had ever seen. Discovered deep in the heart of a treacherous cave system - as if they'd been placed there deliberately - were 15 ancient skeletons that showed a confusing patchwork of features.

Some aspects seemed modern, almost human. But their brains were as small as a gorilla's, suggesting Homo naledi was incredibly primitive. The species was an enigma.

Now, the scientists who uncovered Homo naledi have announced two new findings: they have determined a shockingly young age for the original remains, and they found a second cavern full of skeletons.

The bones are as recent as 236,000 years, meaning Homo naledi roamed Africa at about the time our own species was evolving. And the discovery of a second cave adds to the evidence that primitive Naledi may have performed a surprisingly modern behaviour: burying the dead.

"This is a humbling discovery for science," said Lee Berger, a paleoanthropologist at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. "It's reminding us that the fossil record can hide things … we can never assume that what we have tells the whole story."

Berger and his colleagues report Naledi's age and the new chamber in two papers published Tuesday in the open-access journal eLife.

In a third paper, they argue that Naledi must be a long-lasting lineage that arose 2 million years ago during the early days of the genus Homo and somehow survived long enough to coexist with modern humans, who emerged about 200,000 years ago.

The species' complicated anatomy and unexpected resilience raise a number of intriguing questions, they say: was Naledi a result of, and perhaps a contributor to, hybridisation within the Homo family tree?

Could Naledi be responsible for some of the stone tools found in South Africa during the period it was alive? Should palaeoanthropologists shift their focus from East Africa to the continent's less-studied southern regions?

Several scientists not involved the Naledi research urged caution about some of Berger's bolder claims, including the suggestion that Naledi was burying its dead and crafting the sophisticated stone tools that characterise southern Africa's 'Middle Stone Age'.

But they agreed with Berger on this point: Naledi reminds us that human history is even richer than we realised.

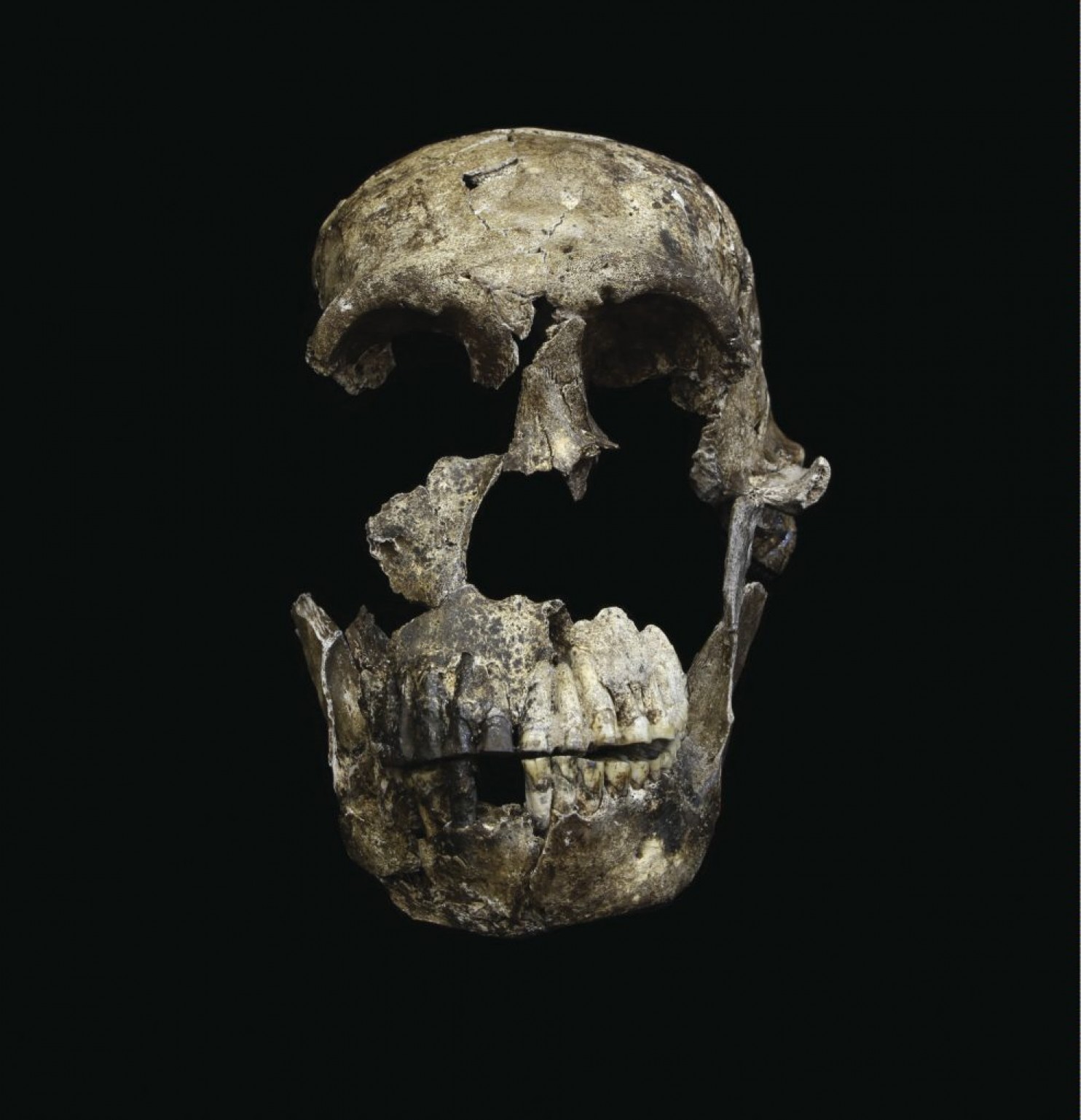

"Neo" skull of Homo naledi from the Lesedi Chamber. Credit: John Hawks/University of the Witwatersrand

"Neo" skull of Homo naledi from the Lesedi Chamber. Credit: John Hawks/University of the Witwatersrand

"The past was a lot more complicated than we gave it credit for and our ancestors were a lot more resilient and lot more varied than we give them credit for," said Susan Anton, a palaeoanthropologist at New York University who was not involved in the research.

"We're not the pinnacle of everything that happened in the past. We just happen to be the thing that survived."

Rick Potts, director of the Human Origins Program at the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History, said finds like this should prompt people to discard the familiar image of a stooped chimp evolving into a modern human walking upright and carrying a briefcase.

"We've had for so long this view that human evolution was a matter of inevitability represented by that march, that progress," he said.

"But now that narrative of human evolution has become one of adaptability. There was a lot of evolution and extinction of populations and lineages that made it through some pretty tough times, and we're the beneficiary of that."

The original Homo naledi skeletons were discovered in 2013 in the Rising Star cave system, one of the twisted and branching limestone caverns that make up a World Heritage Site known as "the Cradle of Humankind".

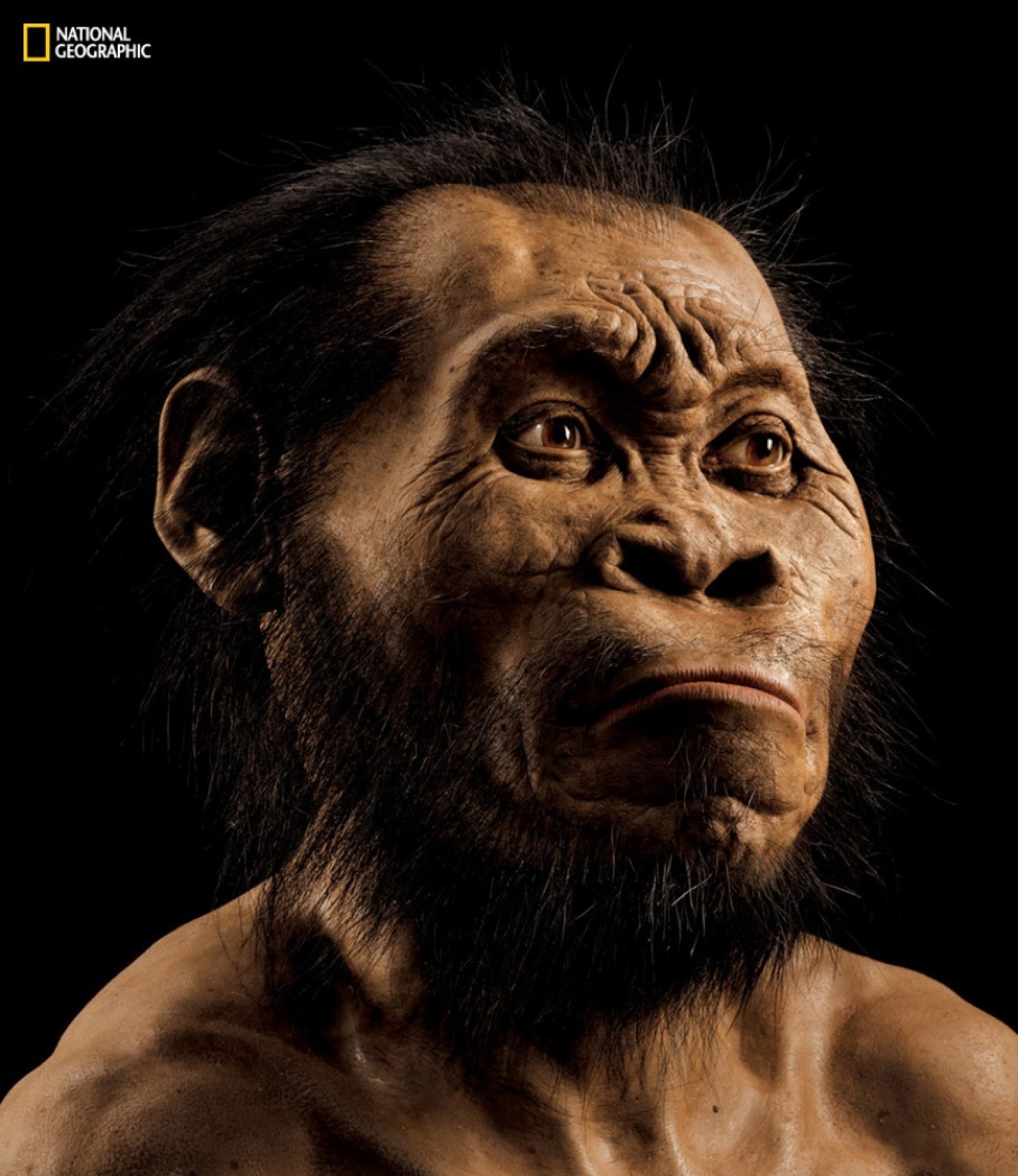

A reconstruction of Homo naledi's head by palaeo artist John Gurche, who spent about 700 hours recreating the head from bone scans. Credit: Mark Thiessen/National Geographic

A reconstruction of Homo naledi's head by palaeo artist John Gurche, who spent about 700 hours recreating the head from bone scans. Credit: Mark Thiessen/National Geographic

This same 180-square-mile region in South Africa has yielded a number of 2-million-year-old Australopithecus fossils, but Homo naledi was the first species to fit in the genus Homo.

The Dinaledi ("star" in the Sesotho language) chamber, which contained the Naledi skeletons, was so narrow and difficult to access that Berger had to seek out an all-women team of petite, extremely agile spelunkers to excavate it.

What they found astonished the paleoanthropology community - not only had a new species been discovered but, with 15 skeletons, it was suddenly the best-documented species in the history of hominins.

And the Rising Star system wasn't done giving up its secrets. Spelunkers Rick Hunter and Steven Tucker, who discovered the bones in the Dinaledi chamber, had also noticed a large leg bone in a different part of the cave.

They didn't think much of it at the time, but after the importance of the Dinaledi fossils became clear, they realised the bone they had passed before was probably from a hominin. As soon as the Dinaledi excavation was complete, the team went back to this second chamber, dubbed Lesedi ("light").

Lesedi was shallower and easier to access than the Dinaledi chamber, but only marginally so. It fit just one excavator at a time, working on his or her hands and knees to brush reddish brown clay from fragile bones.

Berger himself only ventured into the chamber once - he got stuck coming back out of the narrow entrance and decided not to push his luck again.

Yet, somehow, more than 130 hominin bones wound up in this dark and humid cavern hundreds of thousands of years ago. The excavators uncovered remains from at least three Homo naledi individuals. One of them, an adult male they call "Neo" ("gift" in Sesotho), is arguably the most complete fossil hominin ever found.

Berger and his colleagues don't yet have an age for the Lesedi individuals, and without DNA evidence from both caverns, it will be impossible to tell whether they are related to those from Dinaledi.

But he and his colleagues argue that the presence of a second cavern full of bones bolsters the theory that Homo naledi was deliberately leaving its dead in these chambers.

"One, perhaps, was a singular event," Berger said. "Two is not a coincidence."

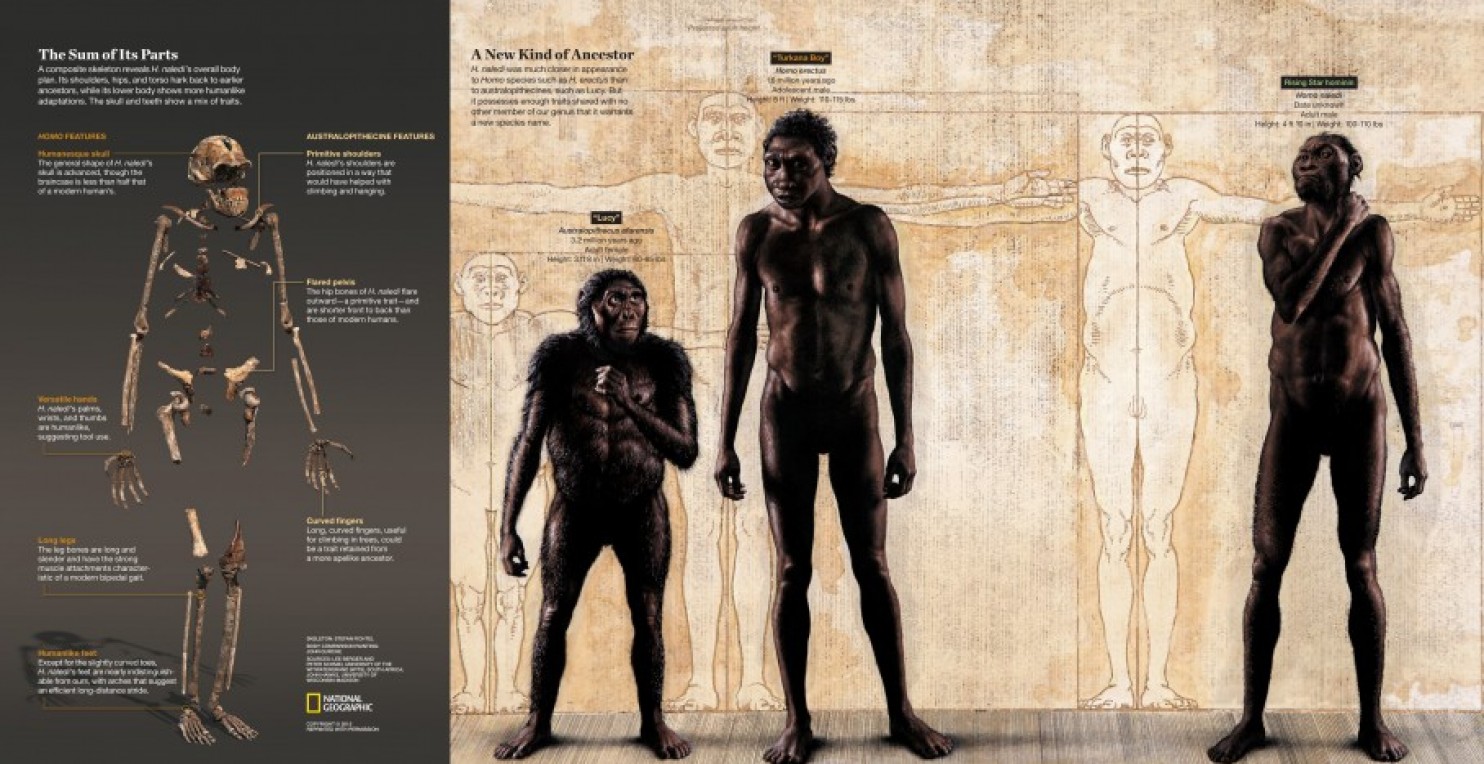

Below you can see a composite skeleton of H. naledi's overall body plan and an illustration of how it compares to Homo species such as H. erectus and Australopithecines such as Lucy:

Skeleton: Stefan Fichtel/National Geographic; body comparison painting: John Gurche; sources: Lee Berger and Peter Schmid, University of the Witwatersrand; John Hawks, University of Wisconsin at Madison

Skeleton: Stefan Fichtel/National Geographic; body comparison painting: John Gurche; sources: Lee Berger and Peter Schmid, University of the Witwatersrand; John Hawks, University of Wisconsin at Madison

Not everyone is convinced. Ritual disposal of the dead is an advanced behaviour, suggesting that a species was capable of symbolic thought and saw itself as separate from the natural world.

Only humans and Neanderthals have been conclusively found to bury their dead, and several scientists said we cannot yet rule out the possibility that the bones were deposited in the cave naturally.

The Lesedi chamber also yielded some small animal fossils. (The absence of nonhuman remains in Dinaledi was considered a strong piece of evidence that the hominins were placed in the cavern intentionally, rather than falling or wandering into the cave and then dying there.)

Alison Brooks, a palaeoanthropologist at George Washington University and the Smithsonian Institution who was not involved in the research, suggested that the immediate ancestors of Homo sapiens might be the ones who put the bodies there.

She said it is possible they dropped the bodies into the caverns through an opening that has long since closed. She noted that no artefacts were found with the caverns that might indicate how to interpret the remains. She also questioned whether the cave was really as difficult to access in the past as it is today.

But if Homo naledi was placing the bones in the cave for ritual reasons, that would mean the species was capable of something profound.

"There's a potential that we are looking at some kind of rudimentary cultural practice associated with this widely shared emotion of grief," said John Hawks, a palaeoanthropologist at the University of Wisconsin at Madison who helped lead the Rising Star expedition.

"It's telling us that this is something that's very deep in our history as humans… When you're looking at a group that takes one of their members and takes the body and put it somewhere hidden, that's like saying, 'We're different. The leopards are not going to eat you. You're one of us.' "

Yet even as the scientists puzzled over the implications of the second cave, they still had to figure out the age of the fossils in the first one.

(L) The skeleton of "Lucy". (R) The skeleton of the roughly 250,000-year-old Homo naledi dubbed "Neo." These are two of the most complete hominin skeletons known to science. Credit: John Hawks/University of the Witwatersrand

(L) The skeleton of "Lucy". (R) The skeleton of the roughly 250,000-year-old Homo naledi dubbed "Neo." These are two of the most complete hominin skeletons known to science. Credit: John Hawks/University of the Witwatersrand

In a 2015 interview with National Geographic (which helped fund the Rising Star excavations), Berger speculated that Naledi had emerged about 2 million years ago, based on its constellation of traits, and was positioned near the root of the Homo family tree.

Homo naledi's small brain case and curved fingers suggested the species was primitive, more closely related to our Australopithecus ancestors than to us. But its long legs, small teeth and dexterous wrists appeared modern.

The bones were too old to be dated using the traditional radiocarbon technique, and too poorly preserved for researchers to extract any ancient DNA.

Meanwhile the stratigraphy, or ordering of the rock layers, of the Dinaledi chamber was difficult to decipher. Water had periodically washed through the cavern during its several-hundred-thousand-year history, causing sediments to accumulate weirdly.

Water also affects radiation levels in the chamber, which can throw off calculations of age based on rates of radioactive decay.

"All this gets quite, quite complicated, and this is one of the reasons why it took so long to do," said Paul Dirks, a geologist at James Cook University in Australia who led the dating effort. "We did not want to put a garbage age out there."

In the end, the research team employed six different dating techniques at 10 labs around the world. Each technique was tried independently by at least two labs to ensure that the results were as robust as possible.

Based on analysis of the Naledi teeth and several measures of radioactivity in the cave, the team concluded that the fossils date back to between 236,000 and 335,000 years ago - just before the arrival of modern humans.

"Our ancestors did not live in a single species world the way we do," Brooks said. "The real take-home message of this paper is that we were not alone until very recently."

Several other hominin species roamed the globe during this period, known as the Middle Stone Age: Homo erectus in Asia; tall, large-brained Homo heidelbergensis in Africa and Europe; eventually Neanderthals and the mysterious Denisovans (who are known only from DNA and a few fossil teeth).

But these species were a lot like us: they walked primarily on two feet, used tools and probably mastered fire. Even the smallest-brained species had a brain that was three-quarters the size of ours.

For years, scientists assumed that all members of the Homo genus in Africa were quite advanced by the Middle Stone Age - how else would they be able to compete with the formidable new species Homo sapiens and its direct ancestors?

Homo naledi complicates that narrative. Its limbs and teeth suggest that it had a human's walking habits and diet, and perhaps roamed the same lands and ate the same foods as our recent ancestors. But its brain was only 30 percent the size of a human's, and no bigger than that of a gorilla today.

"How the heck did these guys survive alongside of us, alongside our ancestors?" Hawks wondered.

Perhaps, he speculated, brain size is not everything. After all, Naledi was arguably able to navigate the Rising Star cave system. He and Berger both suggested the species may have been capable of other feats of intelligence, including crafting the stone tools normally attributed to Homo sapiens and our direct ancestors.

Potts of the National Museum of Natural History, compared Naledi to Homo floresiensis, the tiny, small-brained 'hobbit' people who lived on the Indonesian island of Flores until about 60,000 years ago.

Scientists think that the Flores people descended from taller human species but shrank as a result of "island dwarfism", the tendency of species trapped on islands with limited resources to evolve smaller stature, requiring less food. Perhaps Naledi evolved from a similar phenomenon, Potts said.

"Africa can be seen as an island of forests in a sea of grass," he said. "There are all sorts of refuges that occur and the great biodiversity of Africa emerges through that… Nature constantly experiments in isolated evolution, and this happens to have occurred in our own evolutionary tree, and that's just really neat."

But Berger brushed off the comparison to Homo floresiensis. Southern Africa isn't an island, he said, and Homo naledi did not evolve in isolation.

"We have a very healthy population of individuals that survived f or millions of years and are clearly well adapted to their environment," Berger said. "That has profound implications. You can't just write them off."

Berger and Hawks hedged when asked where Homo naledi might fit on the human family tree.

The late age for the Dinaledi skeletons suggests that the species survived for many years, but more research is needed to pin down when it first evolved.

The species may have emerged near the root of the Homo genus, during an initial phase of diversification that gave rise to Homo habilis and other primitive species. Or it could have branched off later, and may be even more closely related to Neanderthals and modern humans than Homo erectus is.

But both said it might be more accurate to think of human evolution as a stream rather than a branching tree. Tributaries may split off from the main waterway and then loop back; species may diverge, then interbreed.

Naledi, with its amalgam of advanced and primitive features, could be a result of hybridisation. It may also have contributed to the human gene pool: research suggests that many modern humans retain traces of an archaic species in our DNA.

In all likelihood, Hawks said, the full story of human evolution has not been uncovered yet. If a species such as Homo naledi survived for millions of years without us realising it, what else might the fossil record be hiding?

"We keep finding stuff that we didn't think existed," Hawks said. "This is not the first, and it's not going to be the last."

2017 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.