It's long been thought our species was unique in its ability to adapt to harsh climates like bone-dry deserts or thick-set rainforests. Now a new study suggests at least some of our ancestors were adept at living in harsh environments too.

The study comes from an international team of researchers working at the Oldupai Gorge site in Tanzania, who analyzed various excavated items – including bones, plant fossils, sediment, and stone tools – to map out life in the distant past.

A detailed analysis of these remnants was used to recreate the climate and activity of a direct ancestor of modern humans, Homo erectus. The signs point to a hyperarid, relatively inhospitable spot that this ancient species of hominin not only lived in, but returned to several times.

"The biogeochemical, palaeoenvironmental, and archaeological evidence we analyzed suggests early Homo had the ability to adapt to diverse and unstable environments from the East African Rift floor and Afromontane areas as early as two million years ago," says Michael Petraglia, an anthropologist and archaeologist from Griffith University in Australia.

For example, microscopic charcoal residues helped the researchers determine when and where wildfires occurred. Through sediment analysis, meanwhile, the changes in rivers and lakes could be ascertained.

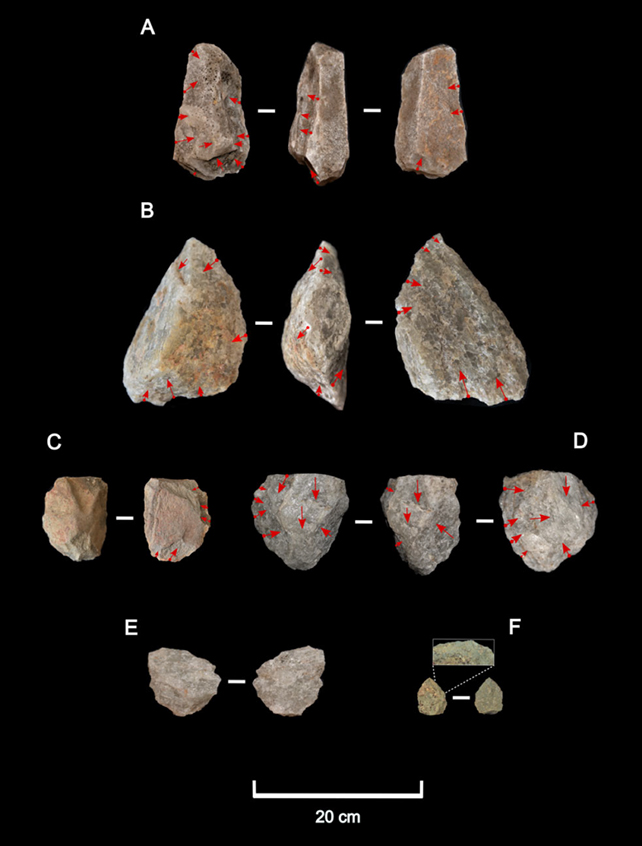

Found in their thousands at Oldupai Gorge, stone tools tell us about how our early ancestors hunted and worked, while the remains of animal bones provide evidence of which animals were killed and how they were butchered.

Taken all together, the evidence suggests ancient hominins were resourceful enough to find ways to eat, drink, and stay alive in the desert. Being adaptable is not something exclusive to H. sapiens after all.

"This adaptive profile, marked by resilience in arid zones, challenges assumptions about early hominin dispersal limits and positions Homo erectus as a versatile generalist and the first hominin to transcend environmental boundaries on a global scale," says Petraglia.

One of several species that preceded modern-day humans, H. erectus was the first of our distant relatives to develop anatomical proportions resembling those of our species. Also the first to migrate out of Africa in large numbers, these people persisted across vast stretches of the planet for more than 1.5 million years before dying out around 110,000 years ago.

That our branche of the family tree now flourishes suggests our species had some advantages in being able to survive in less-than-ideal conditions and spread out into more varied areas of the planet – but it seems we haven't been giving Homo erectus enough credit for sticking around and even thriving in the baking African heat.

"This adaptability likely facilitated the expansion of Homo erectus into the arid regions of Africa and Eurasia, redefining their role as ecological generalists thriving in some of the most challenging landscapes of the Middle Pleistocene," says geologist Paul Durkin, from the University of Manitoba in Canada.

The research has been published in Communications Earth & Environment.