Humans have invisible skin patterns, due to a quirk in how our enveloping layer forms. While we all can't see our own version of hypnotizing tiger stripes or cute cow splotches, it doesn't mean they're not there.

Contrary to some internet rumors, they can't actually be seen by other animals either (no, your cat cannot see your secret stripes). But these patches and stripes can emerge with different skin conditions, including eczema and vitiligo.

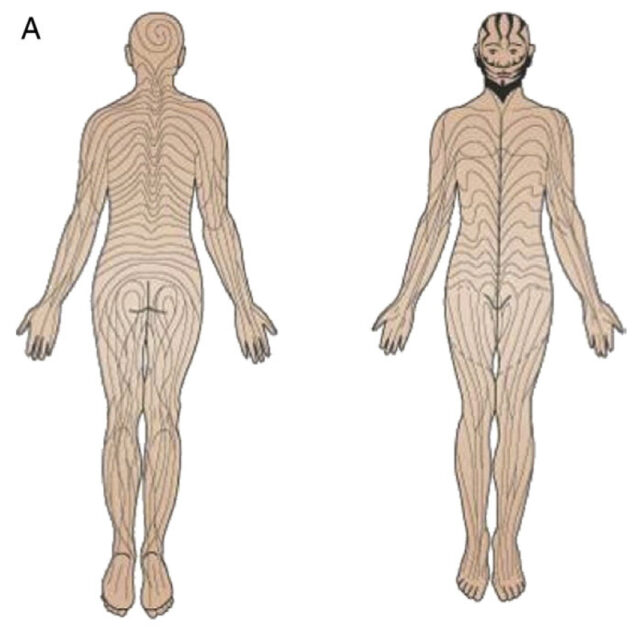

By the turn of the 20th century, German dermatologist Alfred Blaschko had studied the skin of more than 150 patients. He noted the patterns of moles, birthmarks, and other skin conditions across their bodies and discovered they appeared to follow set lines.

The lines seemed to be present at birth and didn't follow any other known body system such as vessels or nerves. Instead, they create sweeping chest arcs, mountainous shapes across the back, and swirling butt loops.

More details, including scalp spirals and neck wriggles, were added to the map 100 years later by physician Rudolph Happle.

These Blaschko lines are now thought to trace the journeys our cells took as they divided and grew into the skin we're now in, during embryonic development. Specifically, they're drawn by the paths of keratinocytes – the main cell in our surface skin – and melanocytes – the cells deep in the epidermis responsible for our skin pigment.

Melanocytes form in the neural crest of an embryo while we're still just a blob of a few hundred cells. Around this stage of development in females, cells start randomly picking which X chromosome to shut off, as we only need one of them active per cell, yet have inherited two, one from mom and one from dad.

So, some of the embryonic cells that give rise to our skin cells will have dad's X chromosome, while others have mom's. All the cells that divide from those early cells will maintain the same epigenetic X chromosome setting, meaning an entire Blaschko line will also share that version of DNA, whereas the line next to it might be the same, or could have the other X.

This is how some of the patterns present as lines, whereas others come out as bigger patches. Such patchworks of genetic patterning are called mosaicism, and can happen with mutations that occur early in development as well, not just traits linked to the X chromosome.

As human pigment color is determined by more than just a gene on our X chromosome, you can't usually see this effect in humans. However, in other animals, coat colour genes are linked exclusively to their X chromosome. This is how we end up with calico cats.

Their color patches clearly mark where each of the two different types of cell lie, one group with mum's X chromosome and the other with dad's.

But some conditions can also make these lines visible in humans, too.

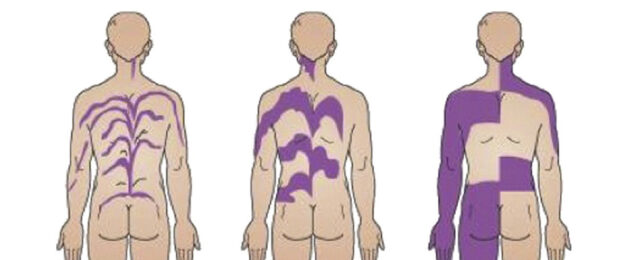

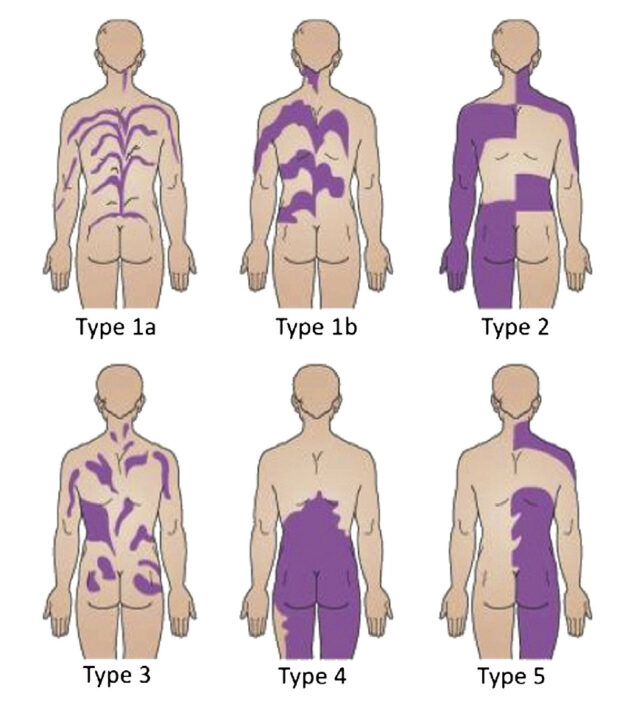

Mutations involving color-producing cells can lead to pigmentary mosaicism presenting as streaks and swirls following Blaschko lines. Type 1a and 1b in the image below are the most typically seen varieties, while the others are less common.

Another rare but extreme example of mosaicism in humans is chimerism. Chimerism is when two different fertilized eggs merge to form a single individual. They can end up with a random combination of two genetically different skin types that most often appear as a checkerboard pattern of mosaicism (type 2).

Some researchers suspect these lines may also explain the way rashes, like dermatitis from poison ivy, spread. More common skin conditions like eczema and psoriasis can also follow the same patterns.

So, while it's fun to speculate what your unique set of Blaschko lines may look like, understanding these patterns can help doctors diagnose skin conditions too.