Declassified satellite images from an old CIA spy program in the Cold War have been used to discover 396 undocumented Roman forts and fort-like buildings.

The snapshots of land were taken in what is now Syria and Iraq in the 1960s and 1970s and were declassified in the 1990s, and, more recently in 2011, only becoming widely available in 2020 and 2021.

Together, the spy data reveal an extensive web of ancient sites that run north to south and east to west on the eastern frontier of the ancient Roman Empire.

The findings, which were put together by researchers at Dartmouth College in the US, upend a century-old assumption regarding these borderlands.

The forts weren't meant to keep foreigners out, argue the researchers, but were built to connect the east and west, enabling safe movement of troops, supplies, and trade.

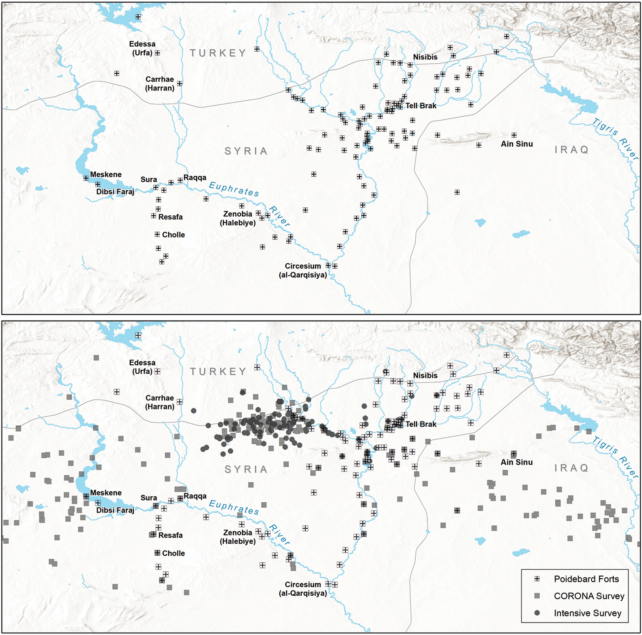

In the 1920s, a Jesuit French priest by the name of Father Antoine Poidebard had the brilliant idea of using airplanes to find the remains of ancient Roman sites in Europe. All along the Empire's eastern frontier, Poidebard's aerial mission revealed hundreds of Roman forts covering over a thousand kilometers of borderland.

Archaeologists and historians have debated the purpose of these sites ever since, but it is generally accepted that the forts run along a rough north-to-south line.

Researchers at Dartmouth argue that that idea is based only on "discovery bias".

Their analysis of spy satellite data now traces a series of Roman forts in the region along an "enormous" east-west axis, connecting parts of the Tigris river in Iraq to western Syria.

"The distribution of these forts suggests that they did not function as a border wall, with a series of towers and fortified encampments designed to block westward incursions by Persian armies or to prevent raids on agricultural villages by nomadic tribes," write the team from Dartmouth.

Instead, the researchers argue for an alternative hypothesis, previously put forward by some archaeologists and historians, which suggests that the forts supported a "system of caravan-based interregional trade, communication, and military transport".

In other words, these forts weren't necessarily barriers against the outer world, but sites of cultural exchange that brought east and west regions together.

This rough horizontal path that researchers at Dartmouth discovered would have enabled caravans to travel safely across the arid Syrian steppe, allowing camels, livestock, and humans a place to stop, rest, drink, eat, and sleep.

For instance, the authors say there is a particularly dense set of Roman sites in Syria near rivers, which would have provided a perennial source of water to travelers.

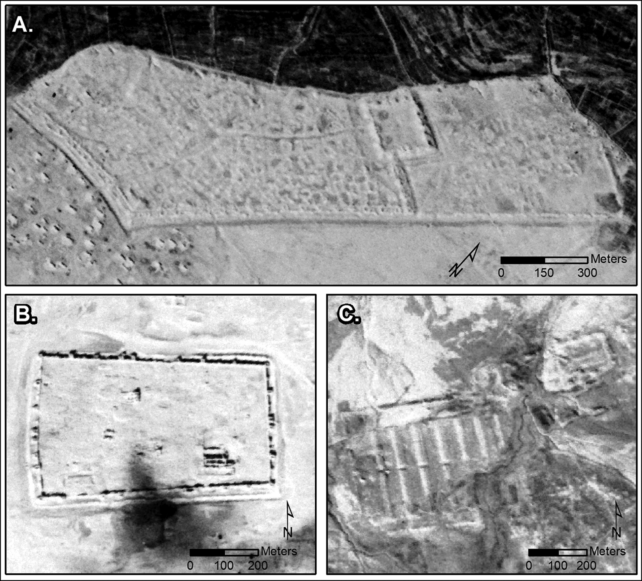

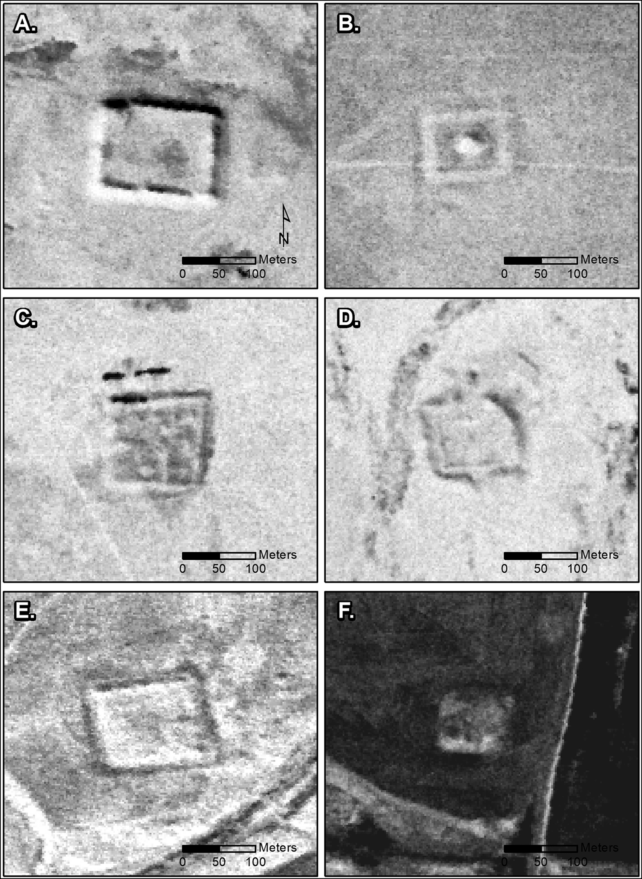

While some of the forts are small and square, like towers, others found via the old spy satellites look like large, complex fortresses with multiple buildings and walls.

Altogether, the findings support the viewpoints of some past scholars, who argued the forts along the north-to-south border are too far apart to represent a wall and were more likely "guarded strategic oases" or defenses against local nomadic groups.

Until work on the ground takes place, it's not clear if all these sites are from Roman times, but given what historians know of the region and the dates of nearby archaeological sites, it would make sense that the forts were built by Romans in the second or third century and abandoned around the sixth century.

"None of this is intended to diminish Poidebard's achievements as a pioneer of aerial archaeological survey, nor the important discoveries he made," write the team at Dartmouth.

"Nonetheless, our results offer a completely new perspective on the distribution of forts across the region and reopen discussions regarding their military, political, and economic functions."

The study was published in Antiquity.