The science connecting climate change to hurricanes like Dorian is strong. Warmer oceans fuel more extreme storms; rising sea levels bolster storm surges and lead to worse floods.

Just this summer, after analyzing more than 70 years of Atlantic hurricane data, NASA scientist Tim Hall reported that storms have become much more likely to "stall" over land, prolonging the time when a community is subjected to devastating winds and drenching rain.

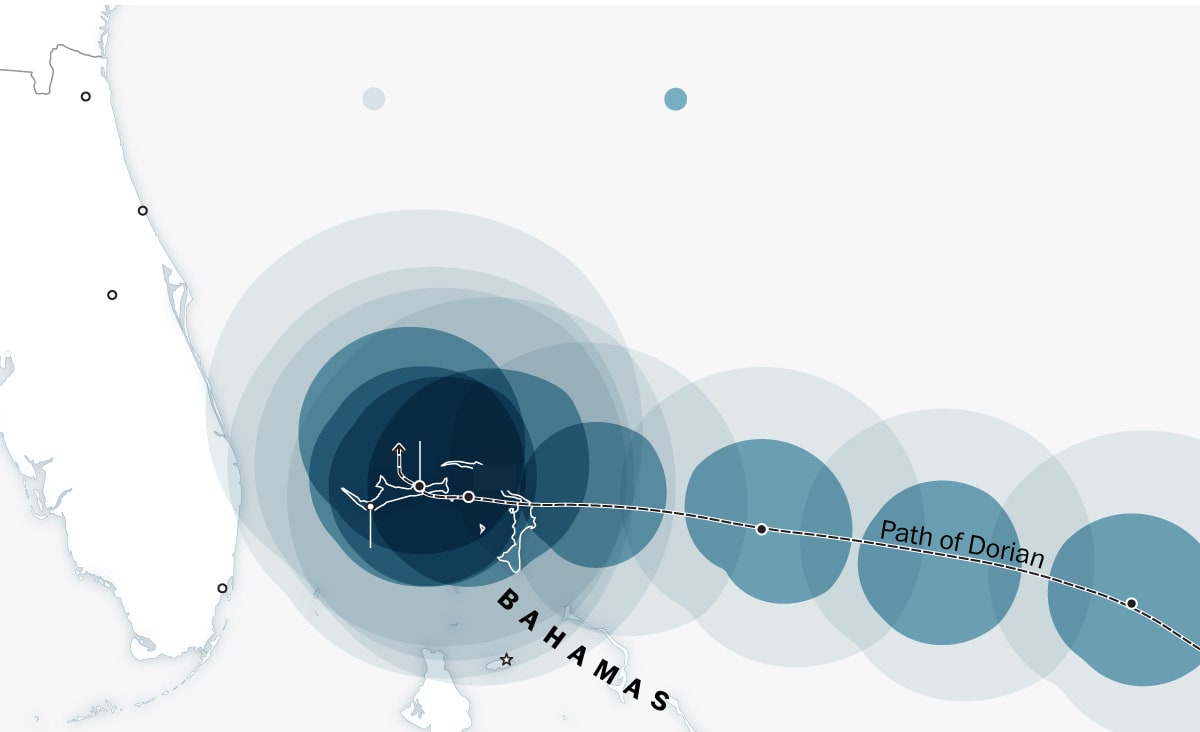

But none of the numbers in his spreadsheets could prepare Hall for the image on his computer screen this week: Dorian swirling as a Category 5 storm, monstrous and nearly motionless, above the islands of Great Abaco and Grand Bahama.

Seeing it "just spinning there, spinning there, spinning there, over the same spot," Hall said, "you can't help but be awestruck to the point of speechlessness".

After pulverizing the Bahamas for more than 40 hours, Dorian finally swerved north Tuesday as a Category 2 storm.

It is expected to skirt the coasts of Florida and Georgia before striking land again in the Carolinas, where it could deliver more life-threatening wind, storm surge and rain.

(The Washington Post)

(The Washington Post)

"Simply unbelievable," tweeted Marshall Shepherd, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Georgia and former president of the American Meteorological Society.

"I feel nausea over this, and I only get that feeling with a few storms."

The hurricane has matched or broken records for its intensity and for its creeping pace over the Bahamas. But it also fits a trend: Dorian's appearance made 2019 the fourth straight year in which a Category 5 hurricane formed in the Atlantic - the longest such streak on record.

Shocking though the storm has been, meteorologists and climate scientists say it bears hallmarks of what hurricanes will increasingly look like as the climate warms.

Dorian's rapid intensification over the weekend was unprecedented for a hurricane that was already so strong. In the space of nine hours Sunday, its peak winds increased from 150 mph to 180 mph (240 km/h to 290 km/h).

By the time the storm made landfall, its sustained winds of 185 mph (298 km/h) were tied for strongest ever observed in the Atlantic.

The link between rapid intensification and climate change is robust, said Jennifer Francis, an atmospheric scientist at Woods Hole Research Center.

Heat in the ocean is a hurricane's primary source of fuel, and the world's oceans have absorbed more than 90 percent of the warming of the past 50 years, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The water that Dorian developed over was about 1 degree Celsius warmer than normal, Francis said: "That translates to a whole bunch of energy."

Because warm air can hold more moisture, climate change has increased the amount of water vapor in the atmosphere, leading to wetter hurricanes that unleash more extreme rainfall.

The warm, wet air also gives further fuel to a growing storm.

"When that water vapor condenses into cloud droplets, it releases a lot of heat into the atmosphere and that's what a hurricane feeds off of," Francis said.

"These factors are very clearly contributing to the storms we've been seeing lately."

Models predict that Category 4 and 5 hurricanes in the North Atlantic could become nearly twice as common over the next century as a result of climate change, even as the total number of storms declines.

Once a hurricane makes landfall, the sea level rise created by global warming can exacerbate its effects by amplifying storm surge. A hurricane's strong winds will push water toward the shore, causing extreme flooding in a relatively short time.

The higher the water level on a clear day, the worse floods will be once a storm arrives - and global sea levels are predicted to rise by about a meter by the end of the century.

Hurricane Dorian was particularly striking - and devastating - because of the way it lingered over the Bahamas. Such "stalling" events have become far more common in the past three quarters of a century, said Hall, who is a senior scientist at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies.

In a study published in the journal Climate and Atmospheric Science in June, Hall found that North Atlantic hurricanes have slowed about 17 percent since 1944; annual coastal rainfall averages from hurricanes increased by about 40 percent over the same period.

A 2018 paper found that tropical cyclones worldwide have slowed significantly.

In stalling events, "you have longer time for the wind to build up that wall of water for the surge and you just get more and more accumulated rain on the same region," Hall said.

"That was the catastrophe of Harvey," he added, referring to the hurricane that dumped more than five feet of rain over Texas in 2017. Hurricanes Dorian and Florence, the latter of which deluged the Carolinas last year, also fit this pattern.

Hall and his colleagues believe there is a "climate change signal" in this phenomenon, though they are still teasing out the link between human-caused warming and slow-moving storms.

Hurricanes have no engines of their own; instead, they are steered across Earth's surface by large-scale atmospheric winds, like corks bobbing in a turbulent stream.

If these guiding winds collapse, or even simply shift around, a hurricane can get caught in an eddy and "stagnate," Hall said.

Climate simulations have shown that atmospheric winds in the subtropics, where Dorian is, are slowing down - making these types of eddies more likely.

"But there are a lot of points in the chain of cause and effect that remain to be elaborated," Hall said.

Such stalling events make hurricanes more difficult to track. Without a known large-scale wind to propel them, the storms are buffeted about by small-scale fluctuations in their environments that are far harder to forecast.

Both Hall and Francis cautioned that scientists can't attribute any single weather disaster to climate change - especially not while that disaster is unfolding.

What researchers can do is evaluate how much worse the disaster was made as a result of human-caused warming, and how likely it is that this type of disaster will occur again.

When it comes to Dorian, Hall said, the answers to both those questions are grim.

"This is what we expect more of," he said. But he doesn't think he'll ever get used to seeing it.

2019 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.