The famed EM Drive is a bust - that's the take-home message from a team of physicists who have tested the controversial fuel-less propulsion system that appears to produce thrust while violating Newton's third law.

Which means physics as we know it might be safe for a little bit longer.

Researchers from TU Dresden in Germany created their own replica of the EM Drive and analysed the amount of force it produced under various conditions - and found it was producing something even when theoretically it should not.

Presenting their results at this year's Aeronautics and Astronautics Association of France's Space Propulsion conference, the physicists admitted something was affecting the system, but it wasn't thrust.

By hanging their replica propulsion system in a vacuum and measuring the movement with a laser, they found they could reverse the field, and even reduce its power - but the drive continued to behave as if it was producing roughly the same amount of force.

This is the story of the little engine that shouldn't – a propulsion system based on a push of electromagnetic radiation that seems to drive forward while contradicting the very physics that explain it.

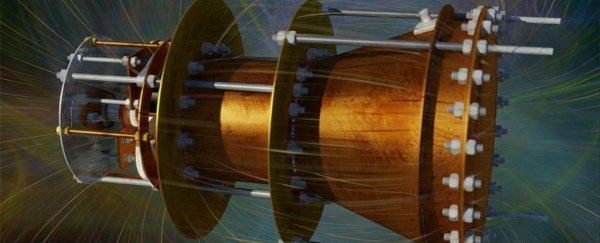

The EM Drive is also known as a 'radio frequency resonant cavity thruster'. Imagine a metal cone containing an electromagnetic field that produces thrust without ejecting any material. If you remember your high school physics, this makes no sense. At least, not without invoking some fringe interpretations of the laws of physics.

Newton figured out that a force is a combination of mass and acceleration. He also worked out they always come in pairs – an action force going one way, and a reaction force going the other.

Unless some kind of mass was being pushed out the back of this thing, an EM Drive based on an kind of propulsion simply shouldn't move itself through empty space.

But as far back as 2001, devices based around this concept have seemed to be doing the impossible by producing a force in a complete vacuum.

Mind you, we're not talking any serious shoving here, with tests conducted by NASA in 2016 indicating it could barely manage a millinewton of force. Cut an apple into a thousand blocks and then hold one of them in your hand, and you'd get some idea of what that amount of push would feel like.

Such a tiny effect was always in the realm of experimental error or outside interference.

Still, the distant promise of an engine that could slowly accelerate an object towards lightspeed without weighing it down with propellants has been too compelling to ignore.

If its effects could be scaled up, such a system could allow us to reach nearby planets in weeks, and even distant stars within single generations.

As recently as last year there have been rumours of research bodies carrying out tests on the device in the hope that there's been a loophole in the laws of physics that could permit such a revolution in space travel.

So, what's happening? There is still a mystery to be solved, but for now it's looking as if that strange pushing motion isn't going to prove useful for space travel.

The researchers from TU Dresden are confident the tiny amount of force is coming from outside of the device, most likely generated by Earth's magnetic field acting on the microwave amplifier. Any future testing would need to shield the cabling in the device from magnetic fields.

No doubt there will be more studies in the future that will work to resolve the question of why the EM Drive behaves as strangely as it does.

History is full of these kinds of disappointments, where small hints of big payoffs are chased in spite of seeming impossibility. Remember cold fusion in the 1980s?

If you're feeling disappointed, don't forget, engineers still have a few tricks up their sleeve to achieve fractional-lightspeed travel.

Those ideas are going to need a lot of work if they're to be realised, but they have a lot more going for them right now than the EM Drive; it might be time we back a different horse and let go of our hopes for possibilities of an impossible propulsion system.

The research was presented at the 2018 Space Propulsion conference in Spain, and is available here.