In its first human trial, the experimental muvalaplin reduced vessel-clogging cholesterol-carriers at impressive rates.

The study, funded by the pharmaceutical's developer Eli Lilly, promises a breakthrough in the search for ways to reduce a form of lipoprotein connected to cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death globally.

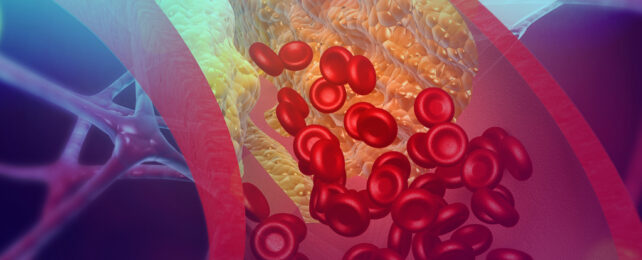

Part protein and part fat (lipid), lipoproteins carry cholesterol around our bodies through our blood. Our cells need cholesterol for many vital tasks, including building their own cell membranes, producing vitamin D and making hormones.

But lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a) for short, is the stickiest of these molecules and has a nasty tendency to clog blood vessels if it gathers with too many of its friends. Recent studies have linked this molecule to heart diseases. It is also involved with poor circulation and strokes.

Once Lp(a) forms it is a massive pain to reduce, with changes in diet and increased exercise having little impact. Attempts to lower the lipoprotein through medication have also met with little success.

Taking a new approach, drug developers are now targeting Lp(a)'s ability to form in the first place.

"Muvalaplin is the first oral agent specifically developed to lower levels of lipoprotein(a) by disrupting its formation," explain Monash Health cardiologist Stephen Nicholls and colleagues in their paper.

In a randomized, double-blind pharmaceutical trial, Nicholls and his team put muvalaplin through its paces with 114 volunteers, involving a mix of sexes, races, and ages (between 18 to 69 years old).

The initial safety evaluation part of the study involved 55 healthy participants taking just one dose of muvalaplin in the range of 1 mg to 800 mg, or a placebo.

A second group consisting of 59 healthy participants, who all had above normal plasma levels of Lp(a), were then given a placebo, oral doses of 30 mg, or doses up to 800 mg.

Within just 24 hours after the first dose, blood plasma levels of Lp(a) dropped. The amount of reduction depended on the dose, reaching up to 65 percent for some patients over the course of the trial.

The reduced Lp(a) levels also lasted up to 50 days after the final drug was taken. Best of all, it did not change levels of any other fats and was well tolerated by all who took it.

Establishing if a new substance is safe for human use is the main goal of a phase one clinical trial such as this, so all potential side effects were assessed in fine detail.

A total of 175 negative experiences were reported during the trial, including headache, back pain and fatigue, nausea and diarrhea. None of these were seen more or less often with dose level, and they were all mild and resolved without any long term consequences.

"These initial phase 1 clinical findings demonstrate that muvalaplin effectively lowers Lp(a) with no serious adverse effects," Nicholls and team conclude.

As this is a small initial trial there is not yet enough evidence to determine the medication's overall efficacy.

Muvalaplin is now undergoing its phase two clinical trial, involving a much larger test population. This will test the effectiveness of the drug with much greater statistical power, before long term risks can then be assessed over multiple years.

This research was funded by pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly and published in JAMA.