The deepest parts of the ocean aren't easy to get to. They're found in fissures in the seafloor, and the creatures there are strange - adapted to the dark, the cold, and the crushing pressure.

But in those trenches, at hadopelagic depths greater than 7,000 metres (20,000 feet), our impact on this world has still been felt. For the first time, in the stomachs of scuttling creatures retrieved from six of the ocean's deepest places, scientists have found plastic.

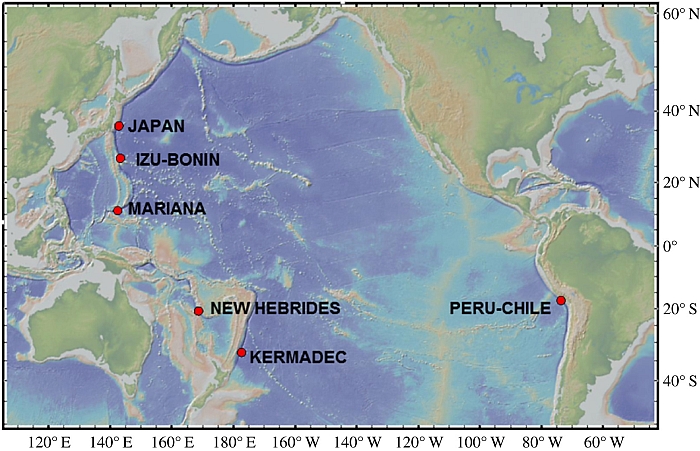

A team of researchers from Newcastle University in the UK sent "landers" to the bottom of the sea in six hadopelagic trenches, across a broad range of sites: Japan, Izu-Bonin, Peru-Chile, New Hebrides, Kermadec, and the deepest known part of the ocean, the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench.

(Jamieson et al., RSOS, 2019)

(Jamieson et al., RSOS, 2019)

Each of these landers is equipped with monitoring and sampling equipment; when they were pulled back to the surface, they had collected a variety of small marine creatures called amphipods for further study.

Between the six trenches, they had collected 90 animals that they studied further, looking for plastic in the hindguts - towards the end of their digestive tracts - to rule out any recent ingestion, such as on the way up from the bottom of the ocean.

They found plastic in the guts of 72 percent of the animals. That's pretty bad. But it gets worse. The deeper they went, the more plastic they found.

From the New Hebrides Trench, plastic was found in 50 percent of the amphipods. But from the Challenger Deep, at a depth of 10,890 metres (35,730 feet), 100 percent of the animals had plastic in their guts.

"This study has shown that man-made microfibres are culminating and accumulating in an ecosystem inhabited by species we poorly understand, cannot observe experimentally and have failed to obtain baseline data for prior to contamination," said marine scientist Alan Jamieson of Newcastle University in 2017, when he revealed the findings.

"These observations are the deepest possible record of microplastic occurrence and ingestion, indicating it is highly likely there are no marine ecosystems left that are not impacted by anthropogenic debris."

Last year, a plastic bag was spotted in the Mariana Trench. Now Jamieson and his team have published the results of their study, showing that this is not an isolated incident. Our garbage is making its way to the bottom of the ocean globally, and we should all be ashamed.

The plastic microparticles, on examination, were mostly semi-synthetic cellulosic fibres used in clothing. The team also found nylon, polyethylene, polyamide, and unidentified polyvinyls closely resembling polyvinyl alcohol or polyvinylchloride - PVA and PVC.

And it's likely that these once-pristine ocean trenches are the last stop for our trash. Once it's there, there's nowhere else for it to go.

"It is intuitive that the ultimate sink for this debris, in whatever size, is the deep sea," Jamieson said. "If you contaminate a river, it can be flushed clean. If you contaminate a coastline, it can be diluted by the tides. But, in the deepest point of the oceans, it just sits there.

"It can't flush and there are no animals going in and out of those trenches."

We don't know what that means for the animals down there, but it may not be good. Ingestion of plastic rubbish is a known killer of sea turtles, and last year we saw multiple whales washed up onto shorelines, killed by plastic pollution.

For amphipods, a gutful of indigestible plastic could affect buoyancy and mobility, making them more vulnerable to predators. And down in the trenches, where food is scarce, the disruption of one source of prey could have a devastating domino effect.

It has impacts for research, too. Recent advances in technology have opened up hadopelagic exploration in unprecedented ways, and we're finding all sorts of exciting new species, such as the Mariana snailfish discovered in 2017.

But humanity has been wreaking plastic havoc for far too long. According to a study published in 2017, by 2015 over 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic had been produced by humans since the 1950s. Over 6.3 billion of those tons had been discarded - ending up in landfill or the natural environment.

It's hard to know exactly how much is making its way into the ocean, but a 2015 study found that the figure was up to 12.7 million metric tons in 2010 alone.

So we have never seen the Mariana snailfish as it existed in an uncontaminated ocean.

"We have no baseline to measure them against. There is no data about them in their pristine state," Jamieson said.

"The more you think about it, the more depressing it is."

The research has been published in Royal Society Open Science.