Scientists studying the skulls of long-dead Incas have made a startling discovery: the patients somehow had twice the survival rate after skull surgery than those operated on during the American Civil War - some 400 years later.

This flies in the face of western notions of technical superiority, and contradicts previous assumptions that the technology and training of the American doctors would automatically result in a better outcome.

The procedure they studied was trepanation, the practice of drilling a hole in the skull. It's been found in skulls around the world, dating back millennia, and is thought to have been employed as a treatment for various ailments - headaches, bone cysts, trauma (such as fractures), convulsive disorders (such as epilepsy), and maybe even expelling demons.

The Inca of Peru were prolific trepanners. Over 800 skulls showing signs of the practice have been recovered from burial caves and archaeological digs from the coastal areas and Andean highlands of Peru, dating back to 400 BCE.

That's more than the total number of trepanned skulls found around the rest of the world.

And, fascinatingly, they show how the Inca surgeons' techniques evolved over time - resulting in an incredible survival rate of over 80 percent.

"There are still many unknowns about the procedure and the individuals on whom trepanation was performed, but the outcomes during the Civil War were dismal compared to Incan times," said neurologist David Kushner of the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

"In Inca times, the mortality rate was between 17 and 25 percent, and during the Civil War, it was between 46 and 56 percent. That's a big difference. The question is how did the ancient Peruvian surgeons have outcomes that far surpassed those of surgeons during the American Civil War?"

Although the techniques used by the Inca are unknown, one answer may be hygiene. Civil War doctors often used unhygienic, unsterilised tools and even their fingers in wounds to help probe them open, and break up blood clots. And shortages forced contaminated dressings to be used again and again.

It was a disgusting time: nearly 100 percent of the survivors of cranial gunshot wounds ended up with an infection.

But the other obvious answer seems to be that the Inca simply had had centuries of practice to perfect their technique.

Kushner's team studied 59 dating from 400 BCE to 200 BCE, from Paracas and the south coast; 421 from 1000 CE to 1400 CE, from the central highlands; and 160 from the Inca period in the early 1400s CE to the mid-1500s CE, from the southern highlands.

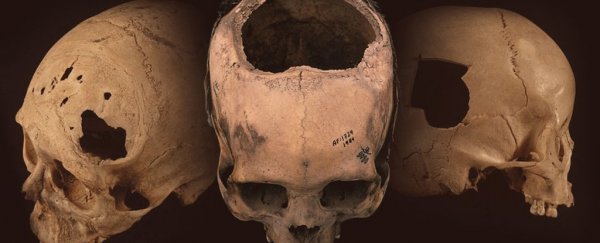

It's a relatively easy task to determine if the trepanation was successful. If the bone around the site of the wound shows signs of advanced healing, that means the patient survived. In this way, the team was able to track a very conspicuous improvement over time.

From the very earliest group of skulls, just 40 percent of the patients survived. By the second group, the survival rate had risen to 53 percent. By the final group, the survival rate had risen to 75-83 percent.

One small group of just 9 skulls from the northern highlands, also from the middle period, showed an astounding 91 percent survival rate.

And the markings on the skulls themselves show technique refinements over time. The holes grow smaller and neater, and the techniques become more careful and precise.

By the Inca period, the surgeons almost exclusively seemed to use a circular grooving technique, which would have resulted in much less penetration of the dura mater - the protective membrane that encases the brain.

"Over time, from the earliest to the latest, they learned which techniques were better, and less likely to perforate the dura," Kushner said.

"Physical evidence definitely shows that these ancient surgeons refined the procedure over time. Their success is truly remarkable."

The team's research has been published in the journal World Neurosurgery.