In a wild feat of biological manipulation that seems straight out of science fiction, researchers have turned parts of living mice see-through.

Stanford University materials scientist Zihao Ou and colleagues developed a biologically-safe dye that makes tissues transparent by tinkering with the light scattering abilities of the cells' surrounding fluids.

It is hoped similar strategies will eventually allow researchers to clearly observe the workings of an organism's innards while they function inside a living body.

"Looking forward, this technology could make veins more visible for the drawing of blood, make laser-based tattoo removal more straightforward, or assist in the early detection and treatment of cancers,″ says Stanford University materials scientist Guosong Hong.

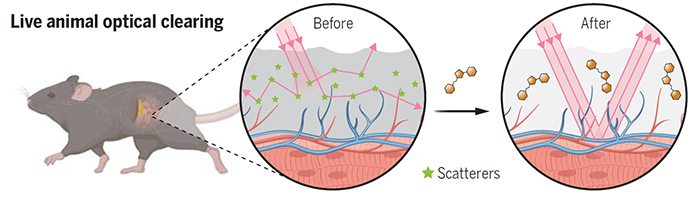

When light of a particular wavelength crosses between materials that have different refractive qualities it scatters in all directions, making the material appear opaque. This is largely why even thin layers of tissue and their surrounding fluids, such as those making up an animal's skin, aren't usually transparent.

Where such biological materials share the same refractive index, light rays could reflect from deeper tissues and can pass across the boundary neatly, providing a level of resolution that would otherwise be lost through scattering. This occurs naturally in some animals already, including Glass frogs (Hyalinobatrachium fleischmanni) and zebrafish (Danio rerio).

One way this could be accomplished in non-transparent tissues is to deliver a substance that absorbs incoming light of very particular wavelengths. A mathematical link between a material's absorption and its refraction based on what's called the Kramers-Kronig relationship means fine-tuning one feature allows the other to change to a precise degree.

The researchers found a food-safe dye called tartrazine could absorb a proportion of light of the right color, allowing the researchers to change the refraction index of the fluid surrounding the cells and reduce scattering significantly.

"The dye is biocompatible – it's safe for living organisms," explains Ou. "In addition, it's very inexpensive and efficient; we don't need very much of it to work."

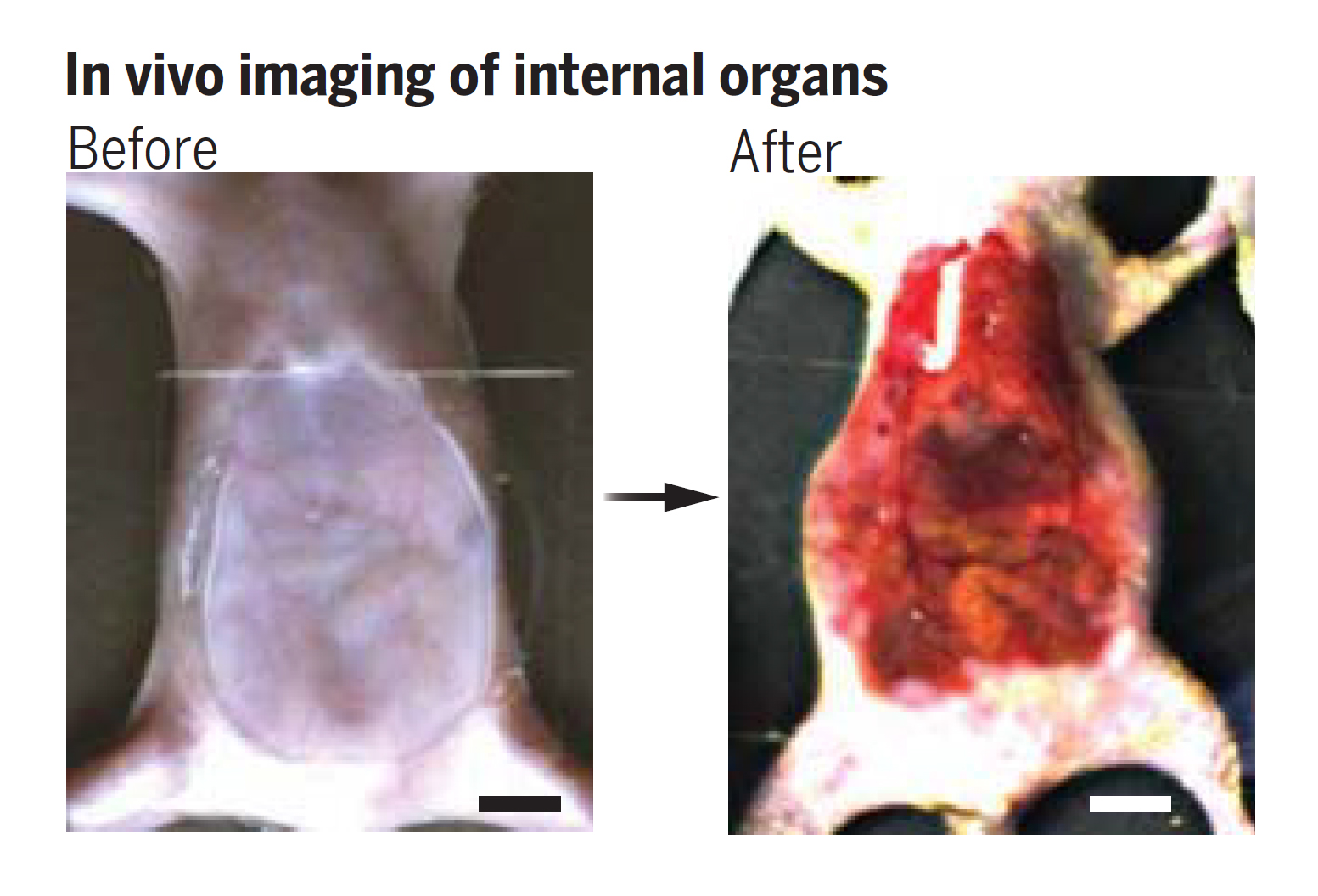

Rubbing a mix of the orange-yellow tartrazine dye and water onto mouse skin allowed the engineers to see details of blood vessels and organs, and even observe the contracting muscles of the test animal's digestive tract.

"It takes a few minutes for the transparency to appear," Ou says. "The time needed depends on how fast the molecules diffuse into the skin."

Once done, the dye can be washed off, allowing the skin to become opaque again. Any tartrazine that penetrates deeper into the body will be eventually peed out.

″As an optics person, I'm amazed at how they got so much from exploiting the Kramers-Kronig relationship – a great example of how fundamental optics knowledge can be used to create new technologies including in biomedicine″ says Adam Wax, program officer for the US National Science Foundation who supported the work.

Human skin, however, is about 10 times thicker than a mouse's, so it is not yet clear if a similar method will work on us. The researchers are keen to explore this next.

This research was published in Science.