Hidden below the waves off the east coast of Australia, scientists have discovered a 'lost world' of epic volcanic peaks buried under the Tasman Sea, never before seen with human eyes.

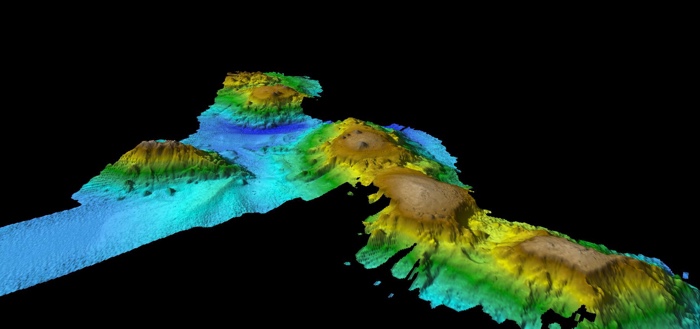

This range of volcanic seamounts - underwater mountains formed by ancient, extinct volcanoes - towers some 3 kilometres (1.9 miles) above the ocean floor. Despite the immense height, it has never been previously detected, since even the highest peaks are concealed 2 km (1.2 miles) below the surface of the South Pacific.

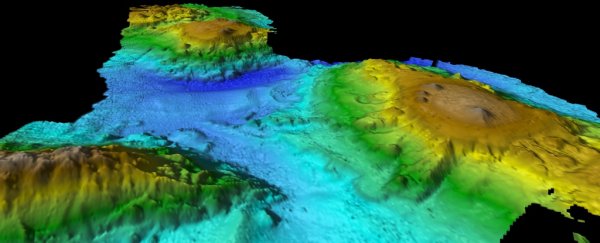

"Our multibeam mapping has revealed in vibrant detail, for the first time, a chain of volcanic seamounts rising up from an abyssal plain about 5,000 metres (16,400 ft) deep," explains marine geoscientist Tara Martin from Australia's CSIRO.

"This is a very diverse landscape and will undoubtedly be a biological hotspot that supports a dazzling array of marine life."

The researchers say the volcanic terrain varies in size and shape, including both sharp peaks and broad plateaus punctuated with smaller conical hills.

The discovery, made aboard the CSIRO research vessel Investigator, occurred during a voyage led by scientists from Australian National University.

The team was examining the relationship between nutrient levels and phytoplankton behaviour in the East Australian Current when their seafloor mapping detected the dramatic, uncharted contours, produced in another era of history.

"We're pretty sure that these seamounts were related to the break up of Australia and Antarctica. It was about 30 million years ago," Martin explained to ABC News.

"As Australia and Antarctica and Tasmania all broke up, a big hotspot came in under the earth's crust, made these volcanoes, and then helped the Earth's crust break so that all of those areas could start to drift apart."

Future research is already being planned to study the terrain and its marine life later in the Australian summer, but already the researchers think these volcanic valleys might serve as a kind of navigational hub for creatures who live in the deep.

(CSIRO)

(CSIRO)

"These seamounts may act as an important signpost on an underwater migratory highway for the humpback whales we saw moving from their winter breeding to summer feeding grounds," one of the team, zoologist and bird researcher Eric Woehler from the University of Tasmania, said in a statement.

"We expect that these seamounts will be a biological hotspot year round, and the summer visit will give us another opportunity to uncover the mysteries of the marine life they support."

In addition to the humpbacks, the researchers found increased ocean productivity over the seamounts, including spikes in phytoplankton activity, plus numerous sightings of other marine life, such as a giant pod of 60-80 pilot whales, and seabirds (four species each of albatross and petrels).

Humpback whale (Eric Woehler)

Humpback whale (Eric Woehler)

Given how new this discovery is, we don't fully understand yet how this lost world and its ocean-dwelling inhabitants interact.

But there's no doubting we've uncovered a vibrant and diverse ecosystem here – a convenient place to stop for food or directions, whether you've got scales, feathers, or mere plankton bits.

Black-browed albatross (Eric Woehler)

Black-browed albatross (Eric Woehler)

"These seamounts act to change the oceanography in these areas," Woehler told ABC News.

"They change the way the water flows around them. They change the dynamics of the system."