The microparticles that leafhopper insects sweat out not only repel water from their wings, but also alter wavelengths of light, which could make them useful to researchers working on the long-running quest to create an invisibility cloak.

Key to inventing such a cloaking device is finding a way to absorb light in a way that hides the object being viewed, and that's exactly what the leafhopper does to evade predators, according to a new study.

Scientists from Pennsylvania State University have come up with synthetic materials that mimic the microparticles used by leafhoppers, using nanoscale holes to absorb light from all directions across a wide range of frequencies.

The material gives us a better idea of why the leafhopper microparticles (called brochosomes) are so effective at camouflaging the insects, and could eventually be used to camouflage almost anything else.

"We knew our synthetic particles might be interesting optically because of their structure," says one of the team, Tak-Sing Wong.

"We didn't know, until my former postdoc and lead author of the study Shikuan Yang brought it up in a group meeting, that the leafhopper made these non-sticky coatings with a natural structure very similar to our synthetic ones."

"That led us to wonder how the leafhopper used these particles in nature."

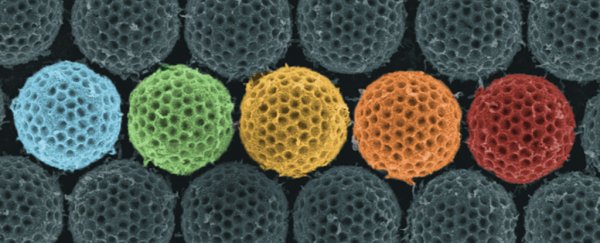

Brochosomes are somewhat like very tiny soccer balls, but up until now scientists have struggled to recreate them with artificial materials.

Using a complex five-step electrochemical process, the researchers managed to produce some similar microparticles of their own, able to capture up to 99 percent of light – from ultraviolet through visible and close to infrared.

Of course no reflected light means nothing to see for any observers passing by.

Close study of these human-made brochosomes revealed more about how the leafhoppers disappearing act could work, because many of the insect's predators, like other insects and birds, view the world through ultraviolet and visible light.

When the synthetic material was placed on leaves, and viewed through a simulated ladybird beetle view (with a restricted vision spectrum), the visible colours of the leaves and microparticles were very close matches.

Being able to produce an invisibility cloak from the stuff is a long way from being viable right now – in fact some physicists say it's impossible, full stop – but the researchers think their leafhopper-inspired findings could be scaled up and might eventually be used in various materials.

"Different materials will have their own applications," says Wong. "For example, manganese oxide is a very popular material used in supercapacitors and batteries. Because of its high surface area, this particle could make a good battery electrode and allow a higher rate of chemical reaction to take place."

As an antireflective coating it could help sensors and cameras reduce signal-to-ratio noise, improve the capabilities of telescopes to peer into deep space, and even help us capture light more efficiently on solar panels.

In all these cases, high absorption rates of energy and light are crucial.

It sounds like we're going to have to do without invisibility cloaks for a little while longer, but the study opens up plenty of new avenues of research, and the team is hopeful that the material could be extended to cover longer wavelengths.

"If we made the structure a little larger, could it absorb longer electromagnetic waves such as mid-infrared and open up further applications in sensing and energy harvesting?" asks Wong.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.