For decades, an ancient circle of stones has lain just out of sight beneath the waters of Spain's Valdecañas Reservoir, its tallest pillars occasionally breaking the surface like the fingers of a drowning swimmer.

Months of intense drought have now caused the reservoir's waters to fall - enough to reveal the structure in its entirety. Given the opportunity to revive research on the circle's archaeology, there's now debate over whether stones should be moved or left for rising waters to reclaim once more.

The 150 stones arranged in an oval are referred to as the Dolmen of Guadalperal. Built by Copper or Bronze Age locals on the banks of the Tagus River, it's thought to be at least 4,000 years old.

Lost to time, the ancient site was rediscovered in the 1920s and sparked interest from German anthropologist Hugo Obermaier, who analysed the architecture and its surrounding mounds of rocks.

The upright pillars – or orthostates – resemble the roughly hewn megaliths of Britain's notorious Stonehenge, not to mention a bunch of other similar constructs around Europe. And it could well have served similar purposes.

Over the generations horizontal slabs were added, forming a structure less like a celestial observatory and more like a tomb or enclosed shelter called a dolmen.

If the site ever hid relics, the usual tides of tomb raiders, vandals, and thieves have long since stripped them away.

Obermaier's investigations did uncover a handful of personal items among the rock piles, suggesting it could once have been a burial site. Symbols such as a human form and possibly a snake carved into a horizontal stone at its entrance also hint at a sacred purpose.

According to the president of the local Roots of Peraleda Cultural Association, Angel Castaño, the Dolmen of Guadalperal was something of a commercial and cultural centre of the area.

But for all of the site's mysteries, in early 20th century time to study the stones was short. Within just a few decades the river was transformed into a reservoir by the Spanish State, swallowing not just the dolmen but a number of other historically significant sites from various periods.

By the 1960s, the ancient structure had all but vanished from view.

This year was a hard one for European farmers. Spain suffered its third driest June of the century this year, and the drought left its mark on the Valdecañas Reservoir, too.

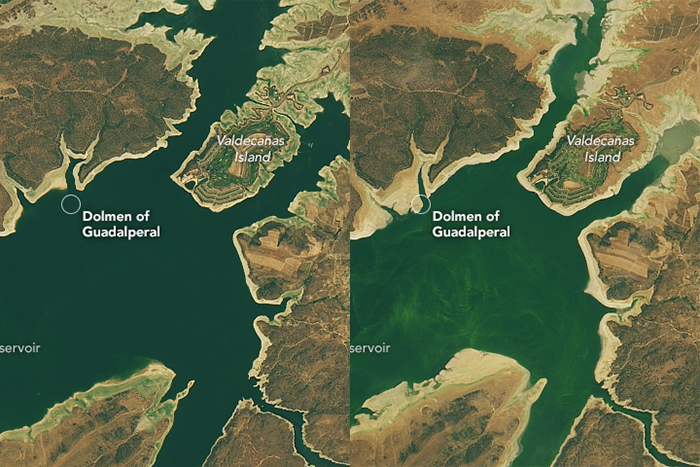

The re-emergence isn't just a sight locals and passing tourists can appreciate. Two snapshots taken from NASA's Landsat satellite in 2013 and earlier this year show just how severe the changes are.

(Landsat 8 - left: July 24, 2013; right: July 25, 2019)

(Landsat 8 - left: July 24, 2013; right: July 25, 2019)

While it was a bad time for agriculture, those interested in local archaeology are making hay while the sun shines.

"All my life, people had told me about the dolmen," Castaño told Atlas Obscura's Alyssa McMurtry.

"I had seen parts of it peeking out from the water before, but this is the first time I've seen it in full. It's spectacular because you can appreciate the entire complex for the first time in decades."

Castaño argues the stones should be relocated somewhere safe, both for further research and to bolster their local tourist industry.

Moving monuments threatened by progress isn't all that uncommon – Egypt's own attempts to tame the Nile have prompted impressive efforts to save ancient temples and statues.

There's even a Change.org petition to raise funds to move the dolmen out of the way of waters that are almost guaranteed to rise again.

But not all archaeologists are so quick to dive in. Historian Primitiva Bueno Ramírez from the University of Alcalá is just as keen as any to learn as much as possible from the site. But rushing in could risk making a mess of things.

"We need high-quality studies using the latest archaeological technology," Ramírez told Atlas Obscura.

"It may cost money, but we already have one of the most difficult things to obtain – this incredible historic monument. In the end, money is the easy part. The past can't be bought."