It may have only been officially discovered in August 2019, but the tremendously exciting interstellar comet 2I/Borisov was already well inside the Solar System at that point. And, after poring over sky survey data, astronomers have found the object appeared in images dating all the way back to December 2018.

The comet's distance at discovery was 3 astronomical units from the Sun - around twice the distance of Mars' average orbit (if off in a wildly different direction). The farthest distance it is visible is around 8 astronomical units - way out past the orbit of Jupiter.

This is a discovery that helps understand the properties of our interstellar visitor, and strengthens calculations of its trajectory. The research has been uploaded to pre-print resource arXiv, and submitted to The Astronomical Journal.

Because of its angle of approach, 2I/Borisov was in what is known as the solar avoidance zone prior to its discovery. This region of the sky is too close to the Sun to return clean observations, since solar radiation creates a lot of noise, which can obscure the signal; and the Sun's powerful radiation can damage some delicate instruments.

The solar avoidance zone is therefore generally, well, avoided; 2I/Borisov was in this region between May and September 2019.

But all-sky time-domain surveys, which sweep the skies looking for changes in cosmic objects, are often looking at the skies when other objects are not. And, because they're optimised to spot things that are out of the ordinary, they are a really good resource for chance observations of objects before they are actually discovered.

(Tony873004/Wikimedia Commons)

(Tony873004/Wikimedia Commons)

So, a team of researchers led by Quanzhi Ye of the University of Maryland tapped into data collected by the Catalina Sky Survey, Pan-STARRS and the Zwicky Transient Facility to see if any of them had caught a glimpse of the comet.

They ran these through software to identify the presence of a comet in the data, and returned an impressive result.

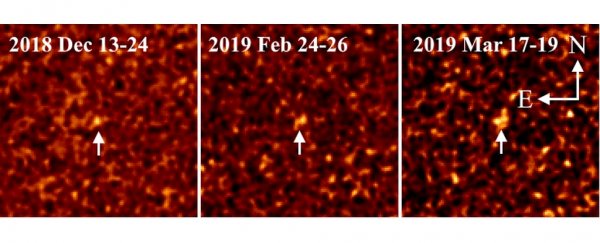

"We identified a total of 202 images from 2018 October 1 to the discovery date of 2I (2019 August 30) that potentially contained the comet," they wrote in their paper.

The earliest detection was on 13 December 2018, at a distance of 8 astronomical units from the Sun. For context, Jupiter's average orbit is 5.2 astronomical units from the Sun.

They also carefully studied the region of the sky where the comet should be, based on its trajectory, in images from November, when it should have been around 8.5 astronomical units from the Sun, and got no result. And that tells us something.

(Ye et al., arXiv, 2019)

(Ye et al., arXiv, 2019)

For one, it allows astronomers to constrain the size of the comet's nucleus - it can, the team said, be no more than 7 kilometres (4.3 miles) in radius. They also believe that the active area of the comet - producing gas - is between 0.5 and 10 kilometres squared. These are both consistent with previous measurements.

Secondly, 2I/Borisov appears to have become active between 5 and 7 astronomical units, sublimating ices - where they transition directly from ice to gas without the intermediate liquid step - to create a fuzzy coma and tail. This, in turn, reveals something about its volatile composition.

Typically, Solar System comets that become active between 3 and 5 astronomical units are sublimating water ice. However, comets that become active between 5 and 8 astronomical units do so due to more volatile molecules, such as carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide.

Since every measurement taken of 2I/Borisov to date suggests it is pretty normal compared to long-period Solar System comets from the Oort Cloud - also known as dynamically new comets - there's no reason to think it will be any different in this regard either.

Which means we may be in for a spectacular show as the comet draws ever closer to the Sun.

"It will be interesting to see if 2I continues to fit into the profile of dynamically new comets. For Solar System comets, it is known that dynamically new comets are 10 times more likely to disintegrate than short-period comets, presumably due to their pristine state and weaker structural strength," the researchers wrote.

"Continued observations of 2I will enable further comparison to dynamically new comets in our Solar System, and provide timely warning for any disintegration (or, as a less dramatic form, outburst) that may happen."

The research has been submitted to The Astronomical Journal, and is available on arXiv.