If you thought the crisis over the gaping hole in the ozone layer was under control, prepare to be disappointed.

Researchers at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) have noticed an unexpected and persistent increase in ozone-destroying chemicals, called chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs).

The Montreal Protocol, which was finalised in 1987, was a revolutionary, international agreement to phase out the production of CFCs, kind of like the modern day Paris accord.

CFC-11, which is one of the banned chemicals, is the second most abundant ozone-depleting gas, commonly used in refrigerants, aerosol sprays, and old styrofoam.

Under the Montreal Protocol, the world agreed to begin phasing out CFC-11, ending its production altogether by 2010.

The protocol was a huge success, slowly shrinking the giant hole that forms over Antarctica each September.

Today, from its peak in 1993, CFC-11 concentrations have declined by 15 percent.

But in the last few years, it looks like someone has started cheating.

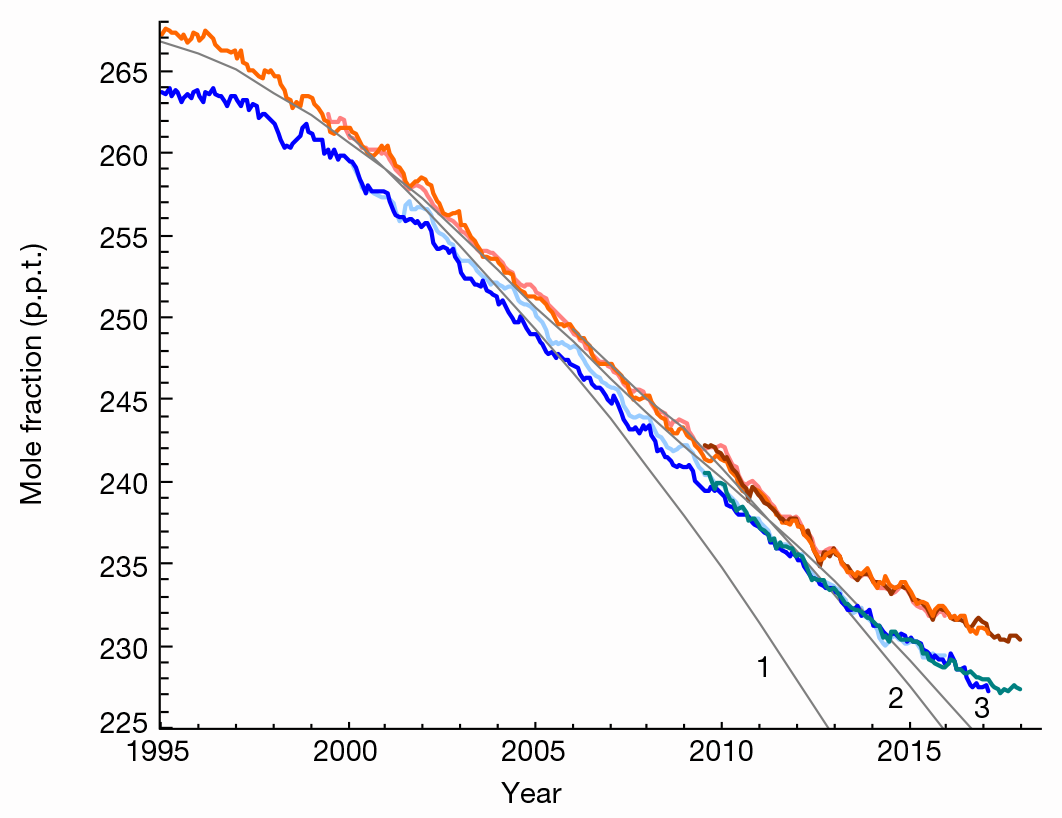

The new study has found that from 2014 to 2016, emissions of CFC-11 have increased by 25 percent above the average measured from 2002 to 2012, slowing the decline of the chemical by 50 percent from 2012.

"It's the most surprising and unexpected observation I've made in my 27 years," said lead author Stephen Montzka, a research chemist at NOAA.

"Emissions today are about the same as it was nearly 20 years ago."

In the chart below, you can see the concentration of CFC-11 in the Northern (red) and Southern (blue) Hemispheres compared to projected decline (gray lines):

(Montzka et al/Nature)

(Montzka et al/Nature)

At first, the researchers hypothesised that the sudden hike in CFC-11 might be due to the destruction of old buildings containing CFC-11 refrigerants. But the data just didn't match up.

And while wind and weather may play a role here, pushing the chemical around and screwing up concentration measurements, weather pattern modelling was not sufficient to explain the uptick.

"In the end, we concluded that it's most likely that someone may be producing the CFC-11 that's escaping to the atmosphere," said Montzka.

"We don't know why they might be doing that and if it is being made for some specific purpose, or inadvertently as a side product of some other chemical process."

The goal of the study was not to point fingers; but figuring out where the emissions are coming from is a crucial environmental question.

If the issue is tackled now, the damage will be minor, Montzka says. But if the problem is allowed to persist, it could jeopardize ozone layer recovery and worsen climate change.

"We're raising a flag to the global community to say, 'This is what's going on, and it is taking us away from timely recovery of the ozone layer,'" said Montzka.

Exploring further, the researchers found the concentration of CFC-11 to be unusually high in the Northern Hemisphere. This was confusing as other gases similar to CFC-11 were not being distributed in the same pattern.

The information has led the researchers to hypothesise that the emissions are coming from the Northern Hemisphere.

Plus, it isn't just CFC-11 that was found to be increasing. When the researchers examined measurements from atop Mauna Loa in Hawaii, they found that other industrial emissions are also increasing.

So where exactly are these increased emissions coming from?

Montzka told the BBC that the data points "fairly definitively" towards Eastern Asia, somewhere around China, Mongolia and the Koreas.

"We are making the measurements from very far away from these regions and I think more specificity is going to come once the people… in that region…look carefully at their measurements and publish their results," he added.

The researchers have calculated that an additional 6,500 to 13,000 tons emitted each year in Eastern Asia would be enough to account for the trend.

To put this in perspective, at peak emissions in the 1980s, the world was producing 350,000 tons of CFC-11 each year, before dropping to 54,000 tons per year at the turn of the century.

If the study is verified, this would be a clear violation of the Montreal Protocol.

"It's disappointing, I would not have expected it to happen," said Michaela Hegglin from Reading University, who was not involved in the study.

"The newer substances that are out there, the replacements for CFC-11, might be more difficult or expensive for some countries to produce or get at."

Nations in the Montreal Protocol have reported close to zero CFC-11 emissions since 2006. Now, it appears someone is going rogue.

The study has been published in Nature.