Astronomers have finally classified a tremendous space explosion first noticed in 2018 - an event so bright, it was thought to have originated much closer to us than we eventually realised. Thanks to two additional discoveries, it now belongs to an entirely new class of giant space explosions.

These bursts of energy are extremely powerful and extremely fast, blasting vast amounts of matter into space at intense velocities. Astronomers have named the new class Fast Blue Optical Transients, or FBOTs.

The 2018 event, nicknamed "the Cow" (AT2018cow), was eventually traced to a galaxy 200 million light-years away, which was a surprise given its exceptional brightness. Since then, it's been outstripped by two even bigger explosions of the same kind, bringing the total of known FBOTs to three.

The two new ones were found in archival data from visible-light all-sky surveys, and followed up with more observations.

They are ZTF18abvkwla, or "the Koala", which was found in data from 2018 observations in a galaxy 3.4 billion light-years away; and CRTS-CSS161010 J045834-081803, or CSS161010, found in 2016 data from a galaxy 500 million light-years away. Two new papers describe the Koala and CSS161010.

To put into perspective just how intense these explosions are, the Cow was at least 10 times more powerful than a regular supernova. The Koala and CSS161010 were more powerful again, but clear similarities exist between all three events.

"When I reduced the data, I thought I made a mistake," said astronomer Anna Ho of Caltech, who led the Koala study. "The 'Koala' resembled the 'Cow' but the radio emission was ten times brighter - as bright as a gamma-ray burst!"

CSS161010 was even more jaw-dropping. The follow-up observations in radio and X-ray wavelengths revealed that the object ejected vast amounts of stellar material into space at a whopping 55 percent of the speed of light.

"This was unexpected," said astronomer Deanne Coppejans of Northwestern University, who led the study on CSS161010, and is apparently a master of understatement.

"We know of energetic stellar explosions that can eject material at almost the speed of light, specifically gamma-ray bursts, but they only launch a small amount of mass - about 1 millionth the mass of the Sun.

"CSS161010 launched 1 to 10 percent the mass of the Sun to relativistic speeds - evidence that this is a new class of transient!"

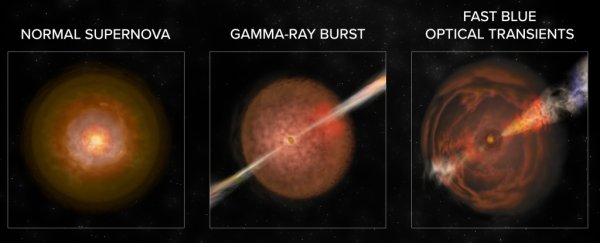

All three explosions share similarities. They look a lot like supernova explosions, but they flare up and fade again incredibly quickly - way more quickly than normal supernovae. They're also incredibly hot, which gives the light a bluer tint, compared to other supernovae.

Because they're so brief, it's hard to get a handle on what causes them. In January 2019, astronomers narrowed down the Cow to two most likely scenarios: a black hole devouring a white dwarf; or an unusual kind of core-collapse supernova leading to the formation of a neutron star or a black hole.

Neither of those two scenarios can be ruled out at this stage, but the astronomers believe what we're looking at here is a very rare kind of supernova.

In the core-collapse supernovae we see more commonly, the supernova blast sheds a spherical shell of stellar material. Sometimes these supernovae also produce a rotating accretion disc of material around the collapsed core that powers extreme, relativistic jets from the poles that propagate gamma rays - what we call a gamma-ray burst.

FBOT explosions, according to the astronomers' model, would also have such a disc and jets, but surrounded by a really dense cloud of material that's not present in normal supernovae. This cloud could have been created by a binary companion stripping the supernova progenitor star of material.

However the cloud is produced, it's the reason for the extreme brightness astronomers have detected. When the shockwave from the supernova collides with the cloud, it produces an extremely fast, hot, bright flash across multiple wavelengths.

The next step in the research will be to pore over more data to potentially identify more such bright flashes, which previously may have been overlooked as glitches. This could help astronomers narrow down even further which scenario is producing these explosions.

But one thing is clear: whatever it is, it's wild.

"We thought we knew what produced the fastest outflows in nature," said astronomer Raffaella Margutt of Northwestern University.

"We thought there were only two ways to produce them - by collapsing a massive star with a gamma ray burst or two neutron stars merging. We thought that was it. With this study, we are introducing a third way to launch these outflows. There is a new beast out there, and it's able to produce the same energetic phenomenon."

The two papers have been published in The Astrophysical Journal and The Astrophysical Journal Letters.