Yet another alarming milestone of humanity's damaging effect on the environment has now officially been reached – crossing a barrier into a hot, polluted future like the planet hasn't witnessed in millions of years.

This weekend, sensors in Hawaii recorded Earth's atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) passing 415 parts per million (ppm) for the first time since before the ancient dawn of humanity.

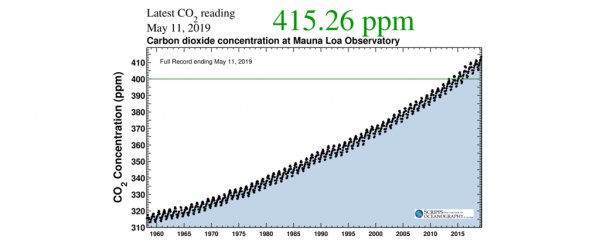

On Saturday, CO2 concentration recorded at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii by researchers from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography hit 415.26 ppm – the latest in a dire series of climatic thresholds being breached by a human society that refuses to relinquish the conveniences afforded by fossil fuels.

"This is the first time in human history our planet's atmosphere has had more than 415 ppm CO2," meteorologist Eric Holthaus tweeted.

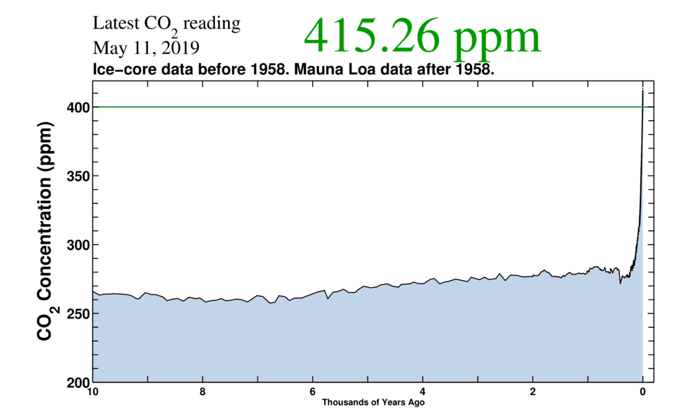

"Not just in recorded history, not just since the invention of agriculture 10,000 years ago. Since before modern humans existed millions of years ago. We don't know a planet like this."

It was only a few years ago that carbon pollution in the atmosphere soared past 400 ppm, and it didn't take long much longer to reach 410 ppm (in 2017).

In fact, with this record-breaking surge in atmospheric carbon poisoning the skies and trapping Earth's heat, scientists knew hitting 415 ppm in 2019 was all but inevitable.

This month has already seen a number of incremental carbon records broken, including a mistaken reading published on the Scripps website that records the ppm data – The Keeling Curve – which suggested the 415 threshold was actually breached on May 3.

That false data was subsequently revised, but not before a handful of sites reported the grim accomplishment.

This time, unfortunately, there appears to be no doubt of where we've arrived at.

(The Keeling Curve)

(The Keeling Curve)

"The average growth rate is remaining on the high end," said the director of the Scripps CO2 program, Ralph Keeling.

"The increase from last year will probably be around three parts per million whereas the recent average has been 2.5 ppm. Likely we're seeing the effect of mild El Niño conditions on top of ongoing fossil fuel use."

It's that ongoing fossil fuel use that's the real problem here.

As recently as 1910, atmospheric CO2 stood at 300 ppm – higher than it had been for some 800,000 years at least – but jumped up another 100+ ppm over the next century as pollution levels skyrocketed.

Obviously, crossing 400 ppm was a huge symbolic moment, numerically at least, but the symbolism doesn't end there.

If carbon pollution keeps getting thicker in our atmosphere, more and more heat will become trapped on Earth, which will make the future of global warming look like something out of the planet's distant, steamy past hundreds of millions of years ago.

The last time Earth scaled such dangerous heights (and heats), there were trees in the South Pole.

But the alarming hockey stick trajectory of current CO2 ppm increases mean we basically have no idea how bad things could get if we don't stop adding to the problem at such an accelerated rate.

In the worst-case CO2 scenarios, far from now, a broken, uninhabitable Earth would be more like a toxic alien planet than the lush refuge we know today: we're talking clouds breaking apart in the sky and hellish oceans boiling until they evaporate.

"We keep burning fossil fuels," Keeling said last year. "Carbon dioxide keeps building up in the air. It's essentially as simple as that."

The very years we are living in right now are our last opportunity to stop these processes from seizing the reins forever more.

There is still hope, but we can only change this trajectory if we collectively focus on changing the systems driving it, from how we get our energy to how we do economics.