A powerhouse team led by researchers from Google, NASA, and the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, is officially claiming to have achieved the technological milestone of quantum supremacy.

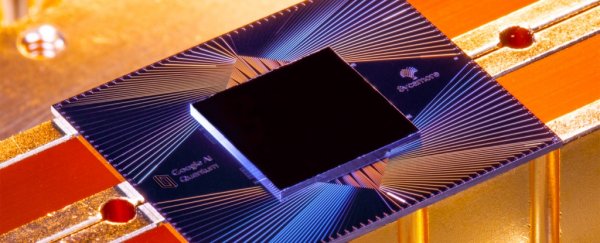

In a new paper released this week, the scientists explain how they developed a quantum processor that could perform a complex computational task in a little over 3 minutes. By contrast, a state-of-the-art classical supercomputer would need about 10,000 years to run the same numbers.

That massive gap in time, in a nutshell, represents something that physicists and computer scientists have long predicted: the threshold where quantum computers become able to solve problems that traditional binary computers (even massively powerful ones) simply cannot, in practical terms.

"This experiment establishes that today's quantum computers can outperform the best conventional computing for a synthetic benchmark," says Travis Humble, the director of Oak Ridge's Quantum Computing Institute.

"There have been other efforts to try this, but our team is the first to demonstrate this result on a real system."

So, we knew this moment was coming. Not just because quantum supremacy as a concept has been envisaged broadly for decades (although the specific term as used today was only articulated in 2012).

But also because you might remember that the Google-led paper leaked early a month ago, giving the world a sneak-peek at the revolutionary claims, now officially published in Nature.

That, uh, preview gave other quantum researchers time to deliberate over Google's experiment and thesis, and not everybody is convinced that the era of quantum supremacy has truly dawned.

Most sensationally, researchers at IBM have claimed that the traditional supercomputer used in Google's experiment (IBM's own Summit machine), wasn't utilised efficiently, which they say explains the less-than-flattering 10,000-year time lag.

By calibrating Summit differently for the same experiment, IBM argues "an ideal simulation of the same task can be performed on a classical system in 2.5 days and with far greater fidelity" – and the researchers have published both a blog post and a working paper to make their case.

Controversies like this, given the extremely technical and scientifically esoteric nature of the research and concepts involved, are not surprising. In fact, they too have been predicted.

"While we believe that some quantum computations will be out of reach of any conventional computer, it is a challenge to argue that any particular set of processes cannot be simulated through some suitable trick," quantum information theorist Stephen Bartlett from the University of Sydney told ScienceAlert last month.

"I suspect that the first claims of quantum supremacy will be followed by a lengthy period of contention, where scientists push the limits of conventional supercomputers to find a way to simulate these claimed demonstrations."

In effect, this technological grey area is where the field may now be focused for some time, as researchers double down, striving to test the limits of advanced, conventional supercomputers against the fledgling abilities of the world's most advanced (and yet still very early) quantum computers.

The debate is not one that ruffles the feathers of the Google-led research team, in any case.

"It is likely that the classical simulation time, currently estimated at 10,000 years, will be reduced by improved classical hardware and algorithms, but, since we are currently 1.5 trillion times faster, we feel comfortable laying claim to this achievement," says one of the group, Brooks Foxen from UC Santa Barbara.

In a call with media, Google's lead researcher John Martinis said IBM's initial retort remained hypothetical, and had to be substantiated.

"We're looking forward to when people actually run the idea on Summit and check it and check our data because that's part of the scientific process – not just proposing it but actually running it and checking it," Martinis said.

"At the same time we'll be making our quantum computers better."

Despite the claims and counter-claims, the fact that several of the world's leading quantum computing scientists are even having this debate suggests that the horizon of quantum supremacy, however messily and contentiously, has been reached.

In a commentary piece on Google's paper, MIT researcher William Oliver likens Google's accomplishment to the Wright brothers' first flights.

"Their aeroplane, the Wright Flyer, wasn't the first airborne vehicle to fly, and it didn't solve any pressing transport problem. Nor did it herald the widespread adoption of planes or mark the beginning of the end for other modes of transport," Oliver writes.

"Instead, the event is remembered for having shown a new operational regime – the self-propelled flight of an aircraft that was heavier than air. It is what the event represented, rather than what it practically accomplished, that was paramount.

"And so it is with this first report of quantum computational supremacy."

The findings are reported in Nature.