Thanks to decades of exploration using robotic orbiter missions, landers and rovers, scientists are certain that billions of years ago, liquid water flowed on the surface of Mars.

Beyond that, many questions have remained, which include whether or not the waterflow was intermittent or regular. In other words, was Mars truly a "warm and wet" environment billions of years ago, or was it more along the lines of "cold and icy"?

These questions have persisted due to the nature of Mars' surface and atmosphere, which offer conflicting answers. According to a new study from Brown University, it appears that both could be the case.

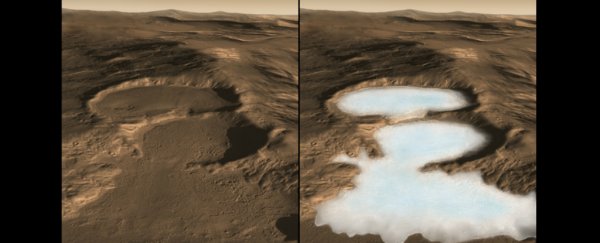

Basically, early Mars could have had significant amounts of surface ice which experienced periodic melting, producing enough liquid water to carve out the ancient valleys and lakebeds seen on the planet today.

The study, titled "Late Noachian Icy Highlands Climate Model: Exploring the Possibility of Transient Melting and Fluvial/Lacustrine Activity Through Peak Annual and Seasonal Temperatures", recently appeared in Icarus.

Ashley Palumbo – a Ph.D. student with Brown's Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Science – led the study and was joined by her supervising professor, Jim Head, and Professor Robin Wordsworth of Harvard University's School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

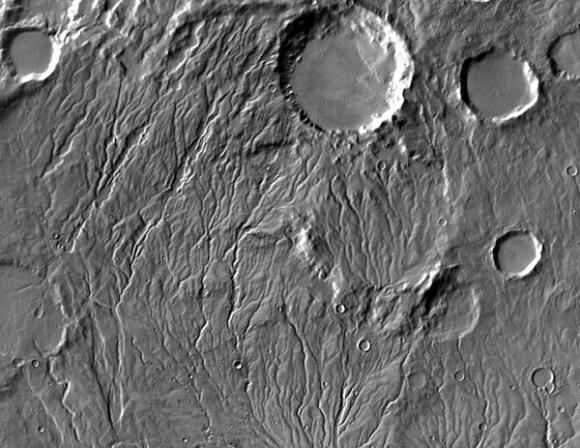

Extensive valley networks suggest Mars once had flowing water. Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Arizona State University

Extensive valley networks suggest Mars once had flowing water. Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Arizona State University

For the sake of their study, Palumbo and her colleagues sought to find the bridge between Mars' geology (which suggests the planet was once warm and wet) and its atmospheric models, which suggest it was cold and icy.

As they demonstrated, it's plausible that during the past, Mars was generally frozen over with glaciers. During peak daily temperatures in the summer, these glaciers would melt at the edges to produce flowing water.

After many years, they concluded, these small deposits of meltwater would have been enough to carve the features observed on the surface today. Most notably, they could have carved the kinds of valley networks that have been observed on Mars southern highlands.

As Palumbo explained in a Brown University press release, their study was inspired by similar climate dynamics that take place here on Earth:

"We see this in the Antarctic Dry Valleys, where seasonal temperature variation is sufficient to form and sustain lakes even though mean annual temperature is well below freezing. We wanted to see if something similar might be possible for ancient Mars."

To determine the link between the atmospheric models and geological evidence, Palumbo and her team began with a state-of-the-art climate model for Mars.

This model assumed that 4 billion years ago, the atmosphere was primarily composed of carbon dioxide (as it is today) and that the Sun's output was much weaker than it is now. From this model, they determined that Mars was generally cold and icy during its earlier days.

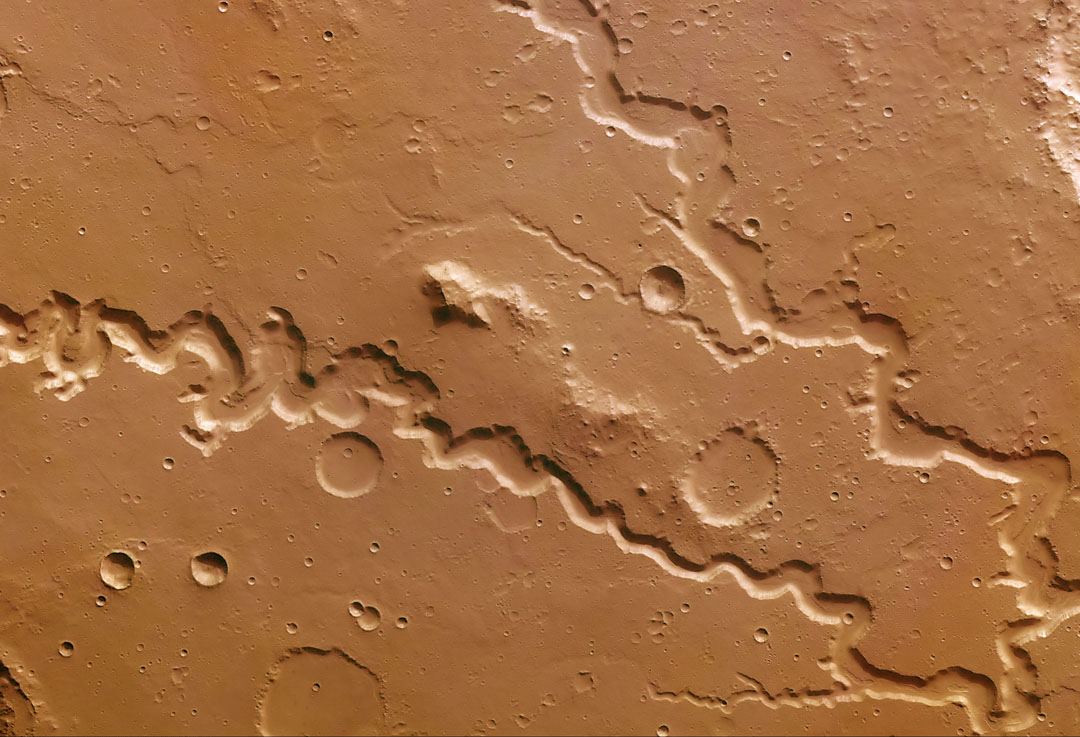

Nanedi Valles. Image: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin (G. Neukum)

Nanedi Valles. Image: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin (G. Neukum)

However, they also included a number of variables which may have also been present on Mars 4 billion years ago. These include the presence of a thicker atmosphere, which would have allowed for a more significant greenhouse effect.

Since scientists cannot agree how dense Mars' atmosphere was between 4.2 and 3.7 billion years ago, Palumbo and her team ran the models to take into account various plausible levels of atmospheric density.

They also considered variations in Mars' orbit that could have existed 4 billion years ago, which has also been subject to some guesswork.

Here too, they tested a wide range of plausible scenarios, which included differences in axial tilt and different degrees of eccentricity. This would have affected how much sunlight is received by one hemisphere over another and led to more significant seasonal variations in temperature.

In the end, the model produced scenarios in which ice covered regions near the location of the valley networks in the southern highlands. While the planet's mean annual temperature in these scenarios was well below freezing, it also produced peak summertime temperatures in the region that rose above freezing.

The only thing that remained was to demonstrate that the volume of water produced would be enough to carve those valleys.

Luckily, back in 2015, Professor Jim Head and Eliot Rosenberg (an undergraduate with Brown at the time) created a study which estimated the minimum amount of water required to produce the largest of these valleys.

Using these estimates, along with other studies that provided estimates of necessary runoff rates and the duration of valley network formation, Palumbo and her colleagues found a model-derived scenario that worked.

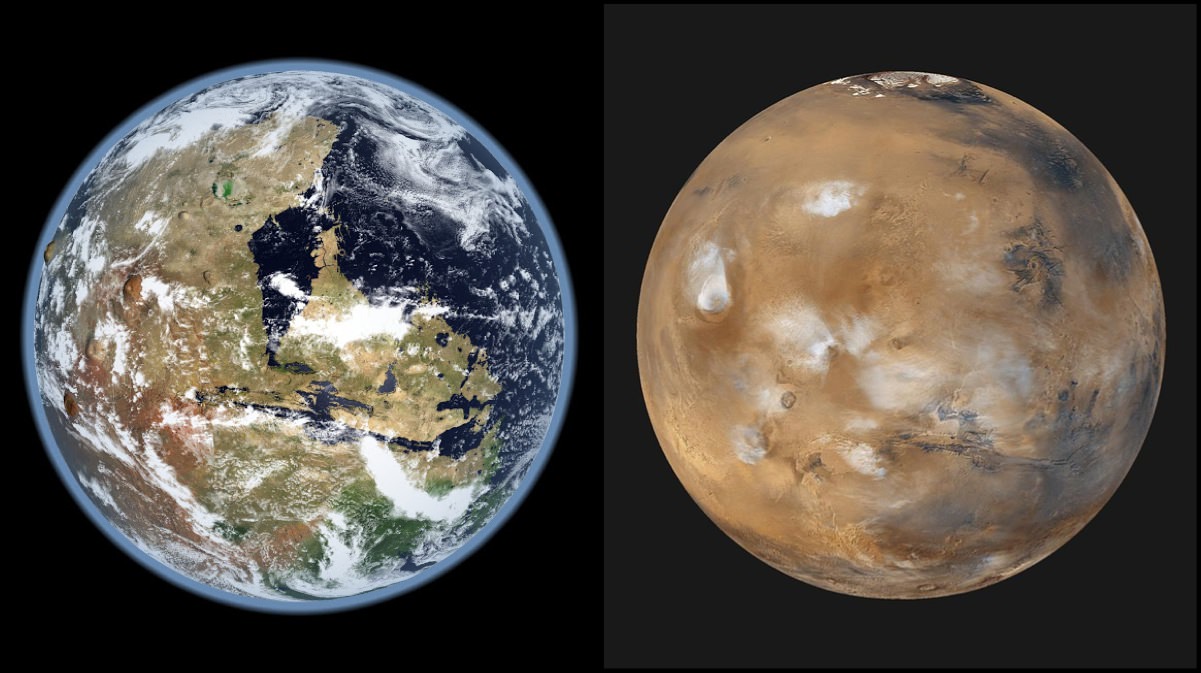

Kevin Gill

Kevin Gill

Basically, they found that if Mars that had an eccentricity of 0.17 (compared to it's current eccentricity of 0.0934) an axial tilt of 25° (compared to 25.19° today), and an atmospheric pressure of 600 mbar (100 times what it is today) then it would have taken about 33,000 to 1,083,000 years to produce enough meltwater to form the valley networks.

But assuming for a circular orbit, an axial tile of 25°, and an atmosphere of 1000 mbar, it would have taken about 21,000 to 550,000 years.

The degrees of eccentricity and axial tilt required in these scenarios are well within the range of possible orbits for Mars 4 billion years ago. And as Head indicated, this study could reconcile the atmospheric and geological evidence that has been at odds in the past:

"This work adds a plausible hypothesis to explain the way in which liquid water could have formed on early Mars, in a manner similar to the seasonal melting that produces the streams and lakes we observe during our field work in the Antarctic McMurdo Dry Valleys. We are currently exploring additional candidate warming mechanisms, including volcanism and impact cratering, that might also contribute to melting of a cold and icy early Mars."

It is also significant in that it demonstrates that Mars climate was subject to variations that also happen regularly here on Earth. This provides yet another indication of how our two plane's are similar in some ways, and how research of one can help advance our understanding of the other.

Last, but not least, it offers some synthesis to a subject that has produced a fair share of disagreement.

The subject of how Mars could have experienced warm, flowing water on its surface – and at a time when the Sun's output was much weaker than it is today – has remained the subject of much debate.

In recent years, researchers have advanced various suggestions as to how the planet could have been warmed, ranging from cirrus clouds to periodic bursts of methane gas from the beneath the surface.

While this latest study has not quite settled the debate between the "warm and watery" and the "cold and icy" camps, it does offer compelling evidence that the two may not be mutually exclusive.

The study was also the subject of a presentation made at the 48th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, which took place from March 20th to 24th in The Woodland, Texas.

Further reading: Brown University, Icarus

This article was originally published with Universe Today. Read the original article.