Scientists are rewriting the story of how modern humans first spread out of Africa, and it might contain more run-ins with Europe's Neanderthals than previously recognized.

Last year, archaeologists uncovered several lines of evidence to suggest that Homo sapiens was living in Europe a whole 10,000 years before we once thought.

That initial group of human migrants might have been the first adventurers to take to the new continent, but they likely weren't the last – nor were they the most successful.

A new analysis of thousands of stone artifacts suggests that in Paleolithic times, our species spread across Europe, taking with us three waves of tool-making technology, each of which replaced the last.

Neanderthal communities already living in Europe might have even thwarted one of these waves.

According to the author of the study, paleoanthropologist Ludovic Slimak, the French Mediterranean is void of tool-making tricks from the second wave of human migration. Yet places further west, like Spain, did host these upgraded tools.

Had Neanderthals in the French Mediterranean rebelled against a return of Homo sapiens?

For at least 12 millennia, Slimak argues, Neanderthals in the Rhône Valley seem to have held human migrants off, though the third wave did eventually replace them.

"These data indicate that the last Neanderthal populations appear to not have retreated into refugia but actually occupy, without sharing for a few millennia, major axes of circulation on the scale of the European continent," writes Slimak.

The analysis, which was conducted at the University of Toulouse in France, is extensive. It covers more than 17,000 stone artifacts that were collected from Lebanon in the eastern Mediterranean. These tools were then compared to artifacts found in the larger Eurasian context.

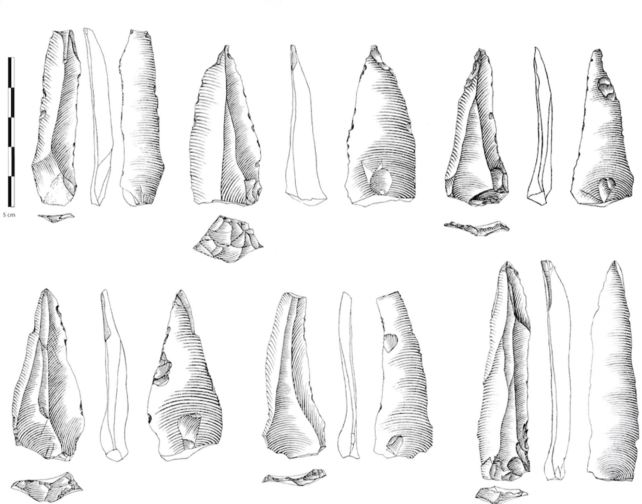

Ultimately, Slimak identifies three distinct phases of tool-making from the results of the Lebanon dig. The oldest tools were made from simple flakes and chips. But later on, weapons like spear throwers and bows appeared with carefully shaped points. In later layers, slender blades became commonplace.

All of these various techniques did not 'bleed into' one another. Instead, they show up abruptly in certain layers. This suggests they were not crafted through gradual evolution but through some burst of cultural invasion.

The first wave of tool technology confirms what Slimak and his colleagues discovered in 2022: that early humans lived in Europe between 51,700 and 56,800 years ago.

The culture of tool-making at this time was consistent among human communities living in France all the way to the Ukraine. Neanderthals, too, seemed to have adopted some of these basic stone-shaping techniques.

But then, suddenly, two clear and intrusive transformations occurred in Lebanon's archaeological record. The first showed up about 45,000 years ago.

It's indicative of the Chatelperronian culture, which is known for shaping smaller, more complex stone blades with backed points elsewhere in Europe. This type of tool-making doesn't show up in human archaeological sites found in France, but it does appear further west in Spain.

That's obviously very far from Lebanon, and Slimak interprets it as a second wave of human migration that seemed to skip France.

"Could it be that in the same geographical space that saw the first migrations of H. sapiens into Europe, Neanderthal groups no longer allowed access to their previous territory?" Slimak wonders.

That's just speculation, but the findings are curious. Why were some waves of human migrants in Europe apparently deterred by Neanderthals? And why was that third and final wave so successful in replacing other native peoples?

Slimak also identifies a third wave of human tool-making in Europe marked by long and slender bladelets. This final wave is present in archaeological evidence from Lebanon across all of Western Europe, including the French Mediterranean, thereby creating a united human cultural front for the first time.

"Until 2022, it was believed that Homo sapiens had reached Europe between the 42nd and 45th millennium," says Slimack.

"The study shows that this first sapiens migration would actually be the last of three major migratory waves to the continent, profoundly rewriting what was thought to be known about the origin of sapiens in Europe."

The study was published in PLOS ONE.