The Cretaceous world seems to have been a perilous place to scratch out an existence, a land of eat-or-be-eaten. And we have evidence of one dinosaur that met such an ignominious end as a feast for an unlikely predator.

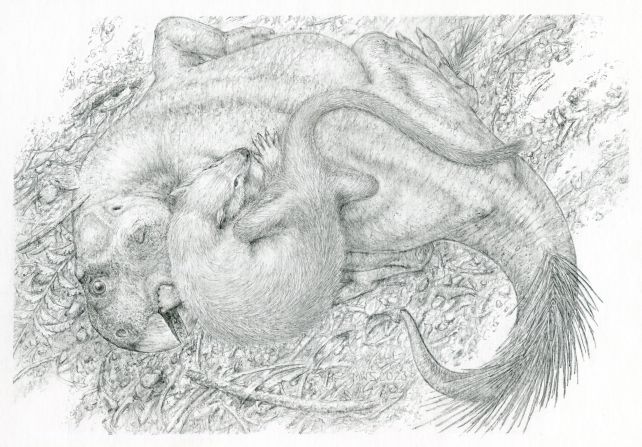

The skeleton of the dinosaur, Psittacosaurus lujiatunensis, is curled, its ribs in the sharp-toothed mouth of a predator, its beaked jaw gripped in a clawed forefoot, and with a hind foot braced against its thigh. The fact of this predation itself is not a surprise, but the predator's identity is a surprise: an opossum-like mammal, much smaller than Psittacosaurus, named Repenomamus robustus.

We knew that R. robustus feasted on smaller, baby Psittacosaurs; this is the first time we've seen evidence that the feisty animals tackled much larger prey.

"The two animals are locked in mortal combat, intimately intertwined, and it's among the first evidence to show actual predatory behavior by a mammal on a dinosaur," says paleobiologist Jordan Mallon of the Canadian Museum of Nature in Canada.

"The co-existence of these two animals is not new, but what's new to science through this amazing fossil is the predatory behavior it shows."

The Psittacosaurus genus lived between around 125 and 101 million years ago and was widespread across what is now Asia, Russia, Mongolia, and Thailand. They had powerful, parrot-like beaks, walked on their hind legs, had clawed forelimbs, and could grow up to around 2 meters (6.6 feet) in length.

R. robostus was the smaller of two Repenomamus species that lived during the early Cretaceous. The larger species could grow up to around the size of a badger. Even so, R. robustus was among the largest mammals in the world at the time. This was still the age of the dinosaurs, and mammals were few.

The fossil of the Psittocosaur and Repenomamus embedded in volcanic rock might not seem surprising at first glance. Many mammals scavenge what they can to eke out a living; the raccoons in your trash are evidence of that. A volcanic flow could have just caught this unlucky mammal while trying for a meal.

However, closer inspection by a team led by paleontologist Gang Han of the Hainan Vocational University of Science and Technology in China revealed that this particular mammal did not appear to be scavenging a carcass.

The bones of the Psittacosaur are neatly in place, with none of the bite marks expected of scavenging. Moreover, the way the two animals are entangled would be unlikely if scavenging was taking place. Nor, probably, would the mammal be on top if the dinosaur was the attacker.

"The weight of the evidence suggests that an active attack was underway," Mallon says.

We know that, in modern times, smaller, aggressive animals can take down larger prey. Pack animals, such as lions or wolves, work together in that regard, but some small lone predators have a scrappy-can-do approach to life that may have been presaged in Repenomamus. Wolverines take down caribou, which are more than 10 times the predator's size. Honey badgers take on oryx, with a similar size ratio.

"This might be the case of what's depicted in the fossil," Mallon says, "with the Repenomamus actually eating the Psittacosaurus while it was still alive – before both were killed in the roily aftermath."

Leaving behind their bones for us to piece together the story millions of years on.

The research has been published in Scientific Reports.