Eight years after the technology was approved by government authorities, it can be reported that at least one child with DNA from three different people has been born to parents in the United Kingdom.

The announcement isn't exactly 'new' knowledge, but reporters at The Guardian were able to prompt an official confirmation with a freedom of information request.

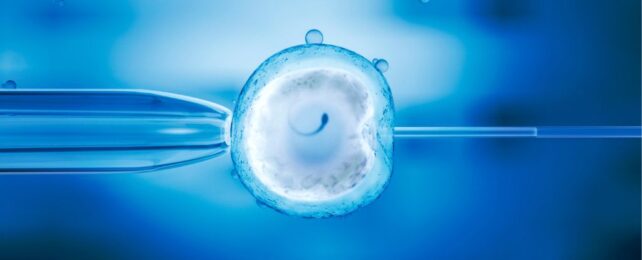

The University of Newcastle in collaboration with the Newcastle Fertility Center are pioneers in what is known as mitochondrial replacement therapy (MRT), a special form of in vitro fertilization (IVF) designed to prevent severe genetic diseases in future babies.

Just like any other person, babies conceived through this method are born from the fertilization of a single sperm and a single egg.

Where they differ is in the relationship between the nuclear material that houses the vast bulk of genes responsible for building a human and the tiny amount of non-nuclear DNA that helps make the cell's power units, called mitochondria.

In most people, a mother's egg provides both the nucleus and a large number of mitochondria. In these children, however, a donated egg is responsible for providing them with their mitochondria supply.

In all, only about 0.1 percent of the child's DNA will be from the donor. But that tiny contribution could make the difference between life and death, allowing people with severe mitochondrial diseases to have a biological child without fear of passing on mutated mitochondrial genes that could struggle to provide sufficient energy for healthy, growing bodies.

The UK was the world's first nation to approve the use of MRT, but to protect the safety and privacy of all those involved, the cases have been kept private.

The Human Fertilization and Embryology Authority (HFEA) has now confirmed that fewer than five babies have been born using the procedure; according to their website, 32 patients have been granted approval for the treatment.

No further information has been provided.

"The Newcastle team involved in carrying out the procedures are cautious and will have wanted to include at least some follow-up data on the babies, while also protecting the privacy of the families," says stem cell biologist and developmental geneticist Robin Lovell-Badge from the Francis Crick Institute, who was not involved in the cases.

"This is a challenge in itself. It will be interesting to know how well the MRT technique worked at a practical level, whether the babies are free of mitochondrial disease, and whether there is any risk of them developing problems later in life or, if female, if their offspring are at risk of having the disease."

A small number of cases in proof of principle studies, for instance, suggest that a mother's mitochondrial DNA may still dominate in babies born using MRT.

Despite leading the way on the therapy, researchers in the UK were not the first to report bringing a 'three-person' baby into the world. Scientists working in Mexico announced in 2016 that a child had been born with DNA from three people.

In 2017, another 'three-person' baby was born in Ukraine, and in 2019, another child was born in Greece.

In the UK, however, cases are kept very private, and researchers are said to be proceeding with caution.

"The HFEA overseas a robust framework which ensures that mitochondrial donation is provided in a safe and ethical manner," says Peter Thompson, chief executive of HFEA.

"All applications for treatment are assessed on an individual basis against the tests set out in the law and only after independent advice from experts. These are still early days for mitochondrial donation treatment and the HFEA continues to review clinical and scientific developments."

A spokesperson for Newcastle team told The Guardian that more information was coming, but that it is in the process of scientific peer review.