Scientists in Japan made progress recently in the quest to combat infertility, creating the precursor to a human egg cell in a dish from nothing but a woman's blood cells.

The research is an important step toward what scientists call a "game-changing" technology that has the potential to transform reproduction.

The primitive reproductive cell the scientists created is not a mature egg, and it cannot be fertilized to create an embryo.

But researchers have already created eggs out of mouse tail cells and fertilized them to produce viable pups, so outside scientists said the research is on track to one day achieve human "in vitro gametogenesis" - a method of creating eggs and sperm in a dish.

"The successful accomplishment of the same in human [cells] is just a matter of time. We're not there yet, but this cannot be denied as a spectacular next step," said Eli Adashi, a former dean of medicine and biological sciences at Brown University who was not involved in the study.

"Considering how difficult this has been in a human, [this new study] in a way broke the ice. When I saw this, I said to myself, 'you know, this [field] is moving.' "

For years, scientists have been working to harness the regenerative potential of stem cells for different purposes, hoping they could be used to regenerate heart muscle or the brain cells lost in Parkinson's disease.

The discovery more than a decade ago that ordinary skin or blood cells can be reprogrammed into stem cells capable of developing into any type of tissue in the body has been one of the most tantalizing frontiers in biomedical research.

Mitinori Saitou, a stem cell researcher at Kyoto University in Japan who led the new study published in Science, has been working for years to apply that approach to egg and sperm cells.

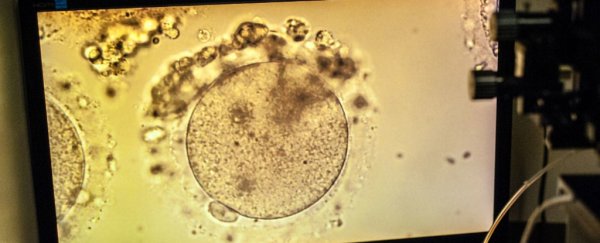

In the new experiment, he created stem cells from human blood cells and then guided them to develop into "primordial" reproductive cells at a very early stage of egg development.

His team was able to keep the cells alive for four months by incubating them in a dish with mouse ovary cells. The cells developed into oogonia, precursors of mature egg cells that appear during the first trimester of pregnancy.

"I think this is an important step, but it's one of several steps that will be necessary before eggs and sperm made from stem cells will be usable," said Henry Greely, director of the center for law and the biosciences at Stanford University, and author of The End of Sex and the Future of Human Reproduction.

"This is farther than anyone has ever gotten with human eggs before, but it is not yet an egg."

Many scientists think it is a matter of when, not if, scientists will be able to create a mature egg - and with that will come a slew of basic safety and mind-boggling ethics questions.

Harvard Medical School stem cell biologist Toshi Shioda pointed out that even after the technical challenges are overcome, a major concern will be the possibility of cancers or other diseases that could arise in any babies created from such an egg.

If the safety questions are answered, the societal and ethical questions begin to multiply. Could someone unknowingly be made a parent without their permission, if someone creates reproductive cells from a cheek smear?

Could women's biological clocks be turned back or eliminated if the need for egg harvesting ends? Would the ease of creating many eggs make in vitro fertilization far more routine?

And could the ease of creating eggs, in turn, allow parents to more routinely screen out genetic diseases?

Scientists say the time to start deliberating about those scenarios, educating the public and talking about oversight is now.

"By the time we see the next science paper . . . that will not be the optimal time to talk about it. There will be potential backlash, adverse actions, that are motivated by who knows what - political, religious, other considerations, that would put this technology in a state of abeyance," Adashi said, adding the technology could be a "game-changer" and the biggest breakthrough in human reproduction since IVF was developed.

In the meantime, Shioda said there will be direct applications for this technology much sooner than any far-off revolution in reproduction.

If researchers create large numbers of developing reproductive cells, they can systematically test and understand how medicines or environmental exposures affect those eggs.

Scientists could better understand how chemotherapy, toxic chemicals or power plant radiation affects reproductive cells.

Saitou said his next goal is to develop a method to bring the oogonia further through development, perhaps by incubating them with embryonic ovarian cells from a human instead of a mouse.

While the research sets off ethical questions, in vitro fertilization was controversial when it was first developed.

Scientists who do work in this area say they receive frequent emails from people who cannot conceive children and wish the technology were ready.

"If we could do this, if it works and is safe, hundreds of thousands or millions of couples in the US could have genetically related babies when they can't today," Greely said.

"There's no obvious reason that it won't work. But the basic thing I've learned about biology is it has a way of surprising us."

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.