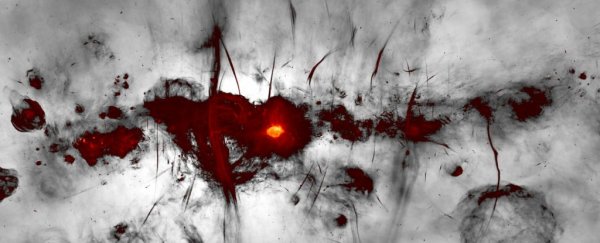

A new image of the heart of the Milky Way is revealing mysterious structures we've never seen before.

Taken using the ultra-sensitive MeerKAT radio telescope in South Africa, the images show nearly 1,000 strands of magnetic filaments, measuring up to 150 light-years in length, in surprisingly neat and regular arrangements.

That's 10 times the number of these strands that we knew about previously, adding important statistical data that might finally help us understand their nature, a puzzle since their discovery in the 1980s.

"We have studied individual filaments for a long time with a myopic view," says astrophysicist Farhad Yusef-Zadeh of Northwestern University, who initially discovered the filaments.

"Now, we finally see the big picture – a panoramic view filled with an abundance of filaments. Just examining a few filaments makes it difficult to draw any real conclusion about what they are and where they came from. This is a watershed in furthering our understanding of these structures."

Although it's only around 25,000 light-years away (which is not very far in cosmic terms), the center of the Milky Way galaxy is very difficult to see into. It's shrouded by dense clouds of dust and gas that block some wavelengths of light, including the optical range. But we can use technology to tweak our vision into invisible wavelengths.

MeerKAT, operated by the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory (SARAO), is one of the world's most advanced radio telescopes, and since opening its eye in 2016, it's been giving us an unprecedented set of insights into the galactic center.

Its latest image is an absolute show-stopper. It was constructed from 200 hours of observation data, collected over three years, and it shows us the region in radio wavelengths with unmatched clarity and depth.

The spectral index of the galactic center filaments. (Northwestern University/SARAO/Oxford University)

The spectral index of the galactic center filaments. (Northwestern University/SARAO/Oxford University)

Yusef-Zadeh and his team then used a technique to remove the background from the image, revealing the magnetic strings distributed in clusters around the galactic center.

It's unclear what they are, or how they came into existence. What we do know is that they contain cosmic-ray electrons, spinning around in filaments of magnetic fields at close to light-speeds.

The new images have allowed the researchers to find out a little more about the strands, bringing us a step closer to understanding them.

"If you were from another planet, for example, and you encountered one very tall person on Earth, you might assume all people are tall. But if you do statistics across a population of people, you can find the average height," Yusef-Zadeh explains.

"That's exactly what we're doing. We can find the strength of magnetic fields, their lengths, their orientations and the spectrum of radiation."

We now know that the magnetic fields are amplified along the entire length of all the filaments. The new data also revealed a previously unknown supernova remnant; it has a different radiation signature from the filaments. This means we can rule out the supernova remnant as a likely progenitor of the filaments.

A spherical supernova remnant discovered by the MeerKAT team. (I. Heywood/SARAO)

A spherical supernova remnant discovered by the MeerKAT team. (I. Heywood/SARAO)

In 2019, previous MeerKAT data revealed the existence of giant radio bubbles extending above and below the galactic plane, separate from the gamma-ray Fermi bubbles discovered in 2010. It's possible that the filaments are related to these radio bubbles, but this possibility will need to be explored in a future paper.

The new data also revealed a new mystery. The filaments are distributed in groups, or clusters, and within those clusters, they're very evenly spaced – like the strings of a harp, the researchers said.

"They almost resemble the regular spacing in solar loops," Yusef-Zadeh says. "We still don't know why they come in clusters or understand how they separate, and we don't know how these regular spacings happen. Every time we answer one question, multiple other questions arise."

We also don't know the mechanism that accelerates the electrons within the magnetic filaments. It's possible that the filaments might be related to a strange magnetic filament, discovered last year, that is emitting radiation in both radio and X-ray wavelengths.

The next step will be to study each filament in turn and characterize its properties for a full catalog that will allow in-depth statistical analyses.

"We're certainly one step closer to a fuller understanding," Yusef-Zadeh says. "But science is a series of progress on different levels. We're hoping to get to the bottom of it, but more observations and theoretical analyses are needed. A full understanding of complex objects takes time."

The research has been accepted into The Astrophysical Journal Letters, and is available on arXiv. A companion paper describing the mosaic, accepted into The Astrophysical Journal, is also available on arXiv. The data has also been released publicly.