It has taken over two decades and one pandemic for paleontologists to unite the fossilized remains of the earliest mammal ancestors and find that their evolution which gave rise to modern humans, may have begun in the Southern Hemisphere – and not in the north as scientists have long thought.

The analysis of a small collection of tiny fossilized jawbones bearing distinctive back teeth flips our understanding of when and where modern mammals evolved on its head, according to the team of researchers who produced it.

Paleontologist Thomas Rich of Museums Victoria co-authored the new study and is a long-time fossil hunter.

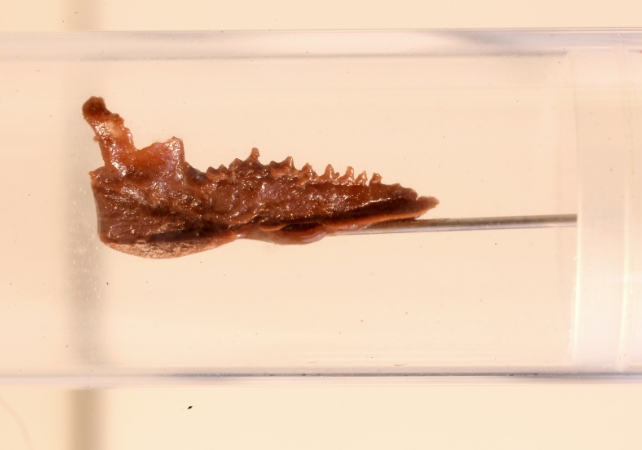

He was part of the team who, in 1997, after 23 years of searching, announced they had found on an Australian beach a mammal jawbone with strange teeth, the likes of which had only been seen in Europe and North America. The jawbone was from a small shrew-like creature and dated back to the Cretaceous period when dinosaurs also roamed.

As the years ticked by, more mammal jawbones from the Mesozoic era were discovered: in Madagascar, Argentina, India, and again, most recently, in Australia.

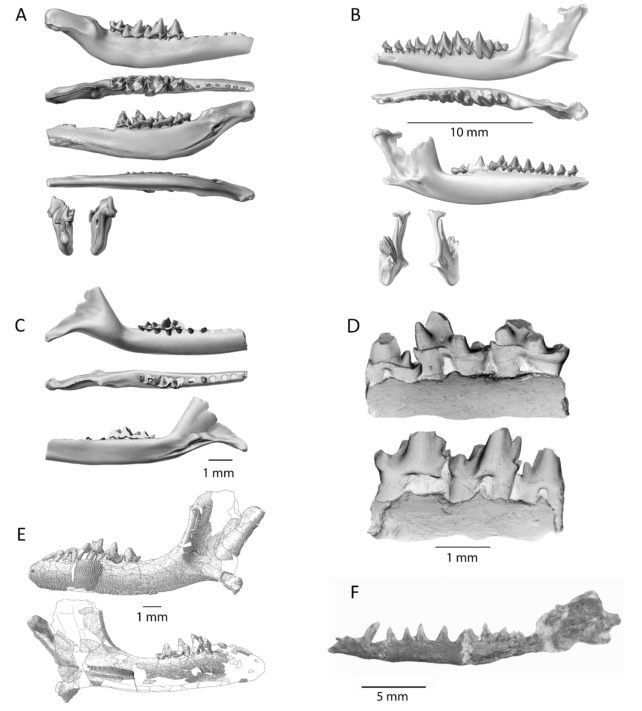

Each of these specimens, measuring an inch or less, had distinctive back teeth. According to the latest analysis which revisits them, the oldest fossil predates those found in the Northern Hemisphere by some 50 million years.

"These astonishing series of discoveries have completely changed our long-held theory of mammal evolution. Indeed, it turns our ideas of mammal evolution on its head," Rich says.

The teensy teeth in question are called tribosphenic molars, which interlock top and bottom to cut, crush, puncture and grind plant food and insect prey.

During the pandemic, esteemed paleontologists Tim Flannery and Kris Helgen, chief scientist at the Australian Museum, had an idea to revisit the three Australian tribosphenic mammal fossils – the most recent of which Rich described in 2020 – and started sifting through the scientific literature to see what else they could find.

They realized these strange teeth united the early mammal fossils found across the Southern Hemisphere and that the Argentinean specimen was the oldest of the lot, millions of years older than any early mammal fossils found in the north.

From there, they mapped out an alternative origin story for mammals, whose ancestors could have hopped between the southern continents when they were joined together in a supercontinent called Gondwana some 125 million years ago before heading north.

Based on the age of the fossils, and their anatomical similarities, the team believes they represent the earliest ancestors of marsupials (such as Australia's koalas and wombats) and placentals (which includes humans), which are grouped together as Therian mammals.

"Our research indicates that Theria evolved in Gondwana, thriving and diversifying there for 50 million years before migrating to Asia during the early Cretaceous," explains Heglen. "Once they arrived in Asia, they diversified rapidly, filling many ecological niches."

The researchers suggest the specialized molars of our earliest mammalian ancestors might have been the key to their evolutionary success. But the evolution of early mammals who outlived the dinosaurs has long fascinated scientists and will no doubt continue to attract ongoing scrutiny.

In paleontology, like any science, the weight of evidence speaks volumes. And for over 200 years, the diversity of mammals living in the Northern Hemisphere and the abundance of fossils found there led scientists to believe that the ancestors of placentals and marsupials arose in the north and spread south.

However, research shows the fossil record can be skewed by who is looking where. For now, all we have to challenge this long-standing theory of where mammals originated is this small collection of tiny teeth – and it has taken several decades to find even those seven specimens.

"It's the most important piece of palaeontological research, from a global perspective, that I've ever published, but it may take some time to find full acceptance among Northern Hemisphere researchers," says Flannery.

It even took him a long time to accept the findings of the analysis. "I resisted the conclusion as long as I could, but the evidence is compelling," Flannery told Australian Geographic's science and environment editor, Karen McGhee.

Indeed, not all paleontologists are convinced. While Flannery and team are holding this new revelation up as a massive discovery that upends our understanding of mammal evolution, Flinders University paleontologist Gavin Prideaux says their conclusions are based on "the tiniest, shittiest little shards" of fossilized teeth.

As he told the Sydney Morning Herald, another interpretation could be one of convergent evolution: that these tribosphenic molar teeth evolved in a few separate places at similar times. "The jury is still out," he says.

The study was published in Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology.