Despite what you might have heard, Jupiter's Great Red Spot is probably not on the point of total disintegration.

The most powerful storm in our Solar System has been shrinking for at least a hundred years, computational physicist Philip Marcus says, but that doesn't mean it's actually dying.

"I don't think its fortunes were ever bad," says Marcus, who works at the University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley).

"It's more like Mark Twain's comment: The reports about its death have been greatly exaggerated."

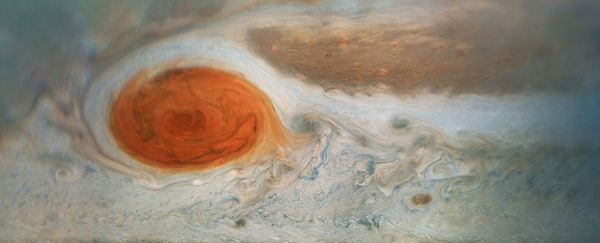

And really, unless you knew better, it would be hard not to fear the worst. Earlier this year, pictures from both astronomers and amateurs captured Jupiter's iconic storm inexplicably shedding red flakes and streams of gas.

The storm's angry red eye looked as though it was suddenly unravelling, sloughing off large chunks of itself bit by bit. Later, NASA's Juno spacecraft captured similar images, as it flew by the storm's edge.

What was actually going on here remained unclear, even to many experts: While some predicted total disintegration, others were not so sure.

(Chris Go)

(Chris Go)

Speaking at an annual meeting for Division of Fluid Dynamics of the American Physical Society, Marcus says talking about the storm's imminent death is premature. Looking over the fluid dynamics of storms on Jupiter, he and his colleagues argue that although the clouds are shrinking, there is no evidence that the storm's hidden vortex is diminishing in size or intensity.

Instead, they say, these are just normal storm dynamics for anticyclones on Jupiter.

Not so long ago, the Great Red Spot was large enough to hold three Earths; now, admittedly, you could only squeeze in one or two. But just because it's smaller, rounder and taller on the outside, doesn't mean this storm is any less powerful at its core.

Using computer simulations, the researchers from UC Berkeley have now shown that surrounding wispy clouds on the boundary of Jupiter's Red Spot can sometimes bump up against other cyclones, spinning in the opposite direction. This, in turn, can cause a collision, which detaches part of the storm and sends it flying.

"It's like having two fire hoses aimed at each other," Marcus told The New York Times.

In all likelihood, he says, this is probably what photographers captured earlier this year. And it's nothing to worry about; it's perfectly natural and healthy for an anticyclone to behave this way.

Unless the jet streams which keep the storm aloft suddenly disappear, Marcus predicts Jupiter's Great Red Spot will continue to survive "for the indefinite future", and probably even longer than that.

"Of course," he admitted at a recent news conference, "I probably just gave it the kiss of death and it'll probably fall apart next week but that's the way science works."

The talk was given at the 72nd Annual Meeting of the American Physical Society Division of Fluid Dynamics.