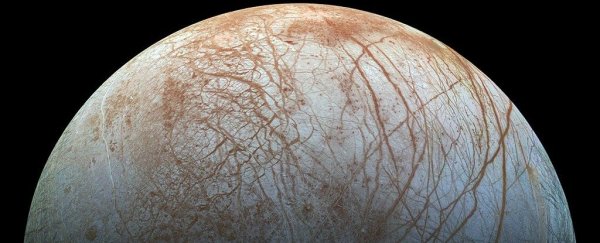

Europa beckons. This distant, icy orb may be only one of Jupiter's almost 80 known moons, but it's what's inside that counts – and what's inside Europa is predicted to be very special indeed.

Under Europa's icy surface, scientists predict the existence of a giant, hidden ocean: a vast reservoir of water that could represent one of our best chances of finding life in the Solar System.

But Europa isn't just a shining hope for discovering life beyond Earth. It may be bright for other reasons, too – a moon that literally glows in the dark, according to new research.

In a new study, a team led by physicist Murthy Gudipati from Caltech and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory suggest that radiation from Jupiter's magnetic field could induce glowing in the icy surface covering Europa, due to reactions with the chemistry of the ice.

"Europa's surface continuously experiences high fluxes of charged particles due to the presence of Jupiter's strong magnetic field," the researchers explain in their paper.

"These high-energy charged particles, including electrons, interact with the ice- and salt-rich surface, resulting in complex physical and chemical processes."

Given we don't fully understand the chemical make-up of Europa's ice cover yet, just what these processes would look like isn't clear, and neither the Keck Observatory in Hawaii nor the Hubble Space Telescope have recorded this hypothetical glow occurring before now.

Sometime in the next decade, though, we might get a better look, when NASA's Europa Clipper spacecraft visits the moon, and has a chance to witness the phenomenon, called electron-stimulated luminescence, up close.

For now, though, we can simulate what it might look like with terrestrial proxies, mimicking both the ice of Europa and the high-energy electron radiation of Jupiter.

In a range of experiments in the lab, Gudipati's team cooled cores of water ice in an aluminium tube, taking the ice down to a temperature of ~100 K (–173.15 °C or –279.67 °F), and subjecting it to pulses of electron radiation.

Visible glowing from the irradiated ice core in lit, dimmed, and dark conditions. (Gudipati et al., Nature Astronomy, 2020)

Visible glowing from the irradiated ice core in lit, dimmed, and dark conditions. (Gudipati et al., Nature Astronomy, 2020)

When they did this, the ice emitted a glow, but the intensity of the illumination depended on what kinds of non-ice chemicals were present in the water.

"Europa ice analogues emit characteristic spectral signatures in the visible region when exposed to high-energy electron radiation," the authors write.

"We found that the presence of sodium chloride and carbonate strongly quenched, while epsomite enhanced, the radiation-induced ice glow."

Beyond suggesting a fascinating hypothesis – that Europa may be continuously glowing in the dark, although we're so far away we can't detect it – the findings could pave the way for new methods to study the icy moon.

Specifically, it's possible that Europa Clipper's imaging systems will be able to observe the glow from orbit (about 50 kilometres or 30 miles above the surface), and in analysing the spectra, shed new light on the chemical composition of the moon's ice, distinguishing non-ice material from regions of pure water-ice.

In addition to helping future studies of Europa, the same techniques could lead to new ways of analysing other Jovian moons too – such as Io and Ganymede – although the researchers concede the wonderful weirdness at work here may turn out to be a one-off.

"Owing to the unique radiation environment and rich geological and compositional diversity on its surface, the night-time ice glow occurring on Europa may be very unique and unlike any other phenomenon in our Solar System," the researchers conclude.

The findings are reported in Nature Astronomy.