New evidence from a comprehensive study suggests that exposure to high concentrations of tiny particles in the air can increase the risk of developing lung cancer within just three years. The research also provides new insights on the disease's progression.

The polluting haze seems to be especially dangerous to healthy lung tissue featuring genetic changes that put it at risk of turning cancerous.

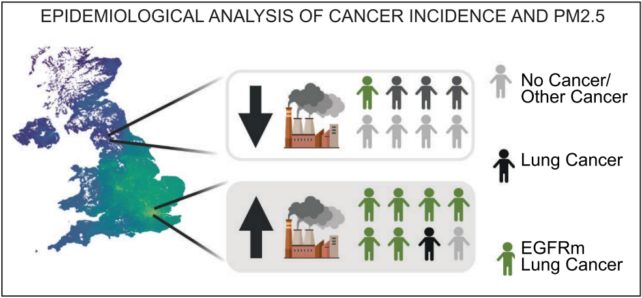

A study of nearly 33,000 people with lung cancer found high levels of critically small pollutants were associated with an increased risk of developing epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-driven lung cancer, which primarily affects non-smokers or people who do not smoke heavily.

"Cells with cancer-causing mutations accumulate naturally as we age, but they are normally inactive," says cancer researcher Charles Swanton from the Francis Crick Institute in the UK.

"We've demonstrated that air pollution wakes these cells up in the lungs, encouraging them to grow and potentially form tumors."

These results, the researchers say, reiterate that air pollution is a major cause of lung cancer, and they emphasize the need for action to reduce pollution and protect public health.

Particulate matter (PM) contributes to air pollution, affecting almost every place on Earth and causing 8 million deaths annually. Fine particulate matter smaller than 2.5 micrometers (PM2.5) can get deep into the lungs and have been linked to numerous health problems, such as heart disease and lung cancer.

"Traditionally, it is thought that carcinogens cause tumors by directly inducing DNA damage," the study authors write in their published paper.

This new evidence supports a 76-year-old idea, Swanton tweeted, "that cancer starts in two steps: the acquisition of a driver gene (initiation) and then a second step whereby a cancer risk factor acts on these latent cells to trigger disease (promotion)."

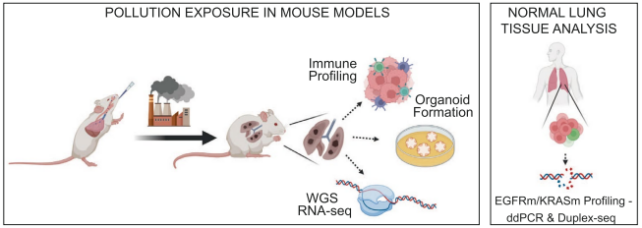

Mouse models also showed that exposure to air pollution caused changes in lung cells that could lead to cancer, with PM2.5 particles appearing to amplify the second step in the process.

To delve into how air pollution causes cancer, Swanton and an international team of researchers conducted a three-part analysis.

Using environmental and epidemiological datasets of 32,957 people from England, Taiwan, and South Korea, they looked at levels of PM2.5 associated with EGFR-mutant lung cancer, which is caused by a mutation in the EGFR gene.

According to the findings, the estimated incidence of EGFR-mutant lung cancer rises as exposure to PM2.5 rises. Further data from 407,509 participants in the UK Biobank corroborated this association.

A smaller dataset of 228 non-smokers in Canada showed that after three years of exposure to high levels of PM2.5 air pollution, the risk of developing EGFR-driven lung cancer increased from 40 percent to 73 percent. This correlation was not found among the same Canadian cohort after 20 years.

"Collectively, these data, combined with published evidence indicate that there is an association between the estimated incidence of EGFR-driven lung cancer and of PM2.5 exposure levels and that 3 years of air pollution exposure may be sufficient for this association to manifest," the authors write.

The team also used an induced EGFR mutation in mouse models to look into the cellular processes that might be behind the growth of cancer in relation to air pollution. They found that PM2.5 seems to cause an influx of immune cells and the release of interleukin-1 (a signaling molecule that causes inflammation) in lung cells.

What's more, blocking interleukin-1 during exposure to PM2.5 was shown to stop cancers caused by EGFR from developing.

This evidence supports that PM2.5 may cause tumors to grow and worsen cancerous mutations that were already there. The authors also found that lung cells called alveolar type II (AT2) cells are more likely to cause lung cancer when PM2.5 is present.

And finally, tests on healthy lung tissue from 295 people revealed that a significant proportion had genetic mutations that could lead to cancer, meaning exposure to high levels of PM2.5 could place their health in more grave danger.

"In summary, 54 out of 295 (18 percent) of samples of non-cancerous lung tissue harbored an EGFR driver mutation," Swanton and co-authors write.

The researchers admit that their work has some limitations. For example, the cancer-prone mouse models will get tumors even without PM2.5, and they probably don't show the full range of mutations found in healthy adult tissue. But they do give scientists a chance to study early tumor growth in a controlled setting.

Co-first author and cancer cell biologist William Hill from the Francis Crick Institute concludes, "Finding ways to block or reduce inflammation caused by air pollution would go a long way to reducing the risk of lung cancer in people who have never smoked, as well as urgently reducing people's overall exposure to air pollution."

The peer-reviewed research has been published in the journal Nature.