The Orion nebula is one of the most studied regions of our sky.

It sits amidst the constellation of Orion, between the stars, and is so large, close, and bright it can be seen with the naked eye: a vast cloud complex giving birth to and nurturing baby stars.

Because it is relatively close, at 1,344 light-years away, it's one of the most important observation targets in the sky for understanding star formation. Although we've been staring at the nebula since it was first officially discovered in 1610, however, we've not unraveled all its secrets.

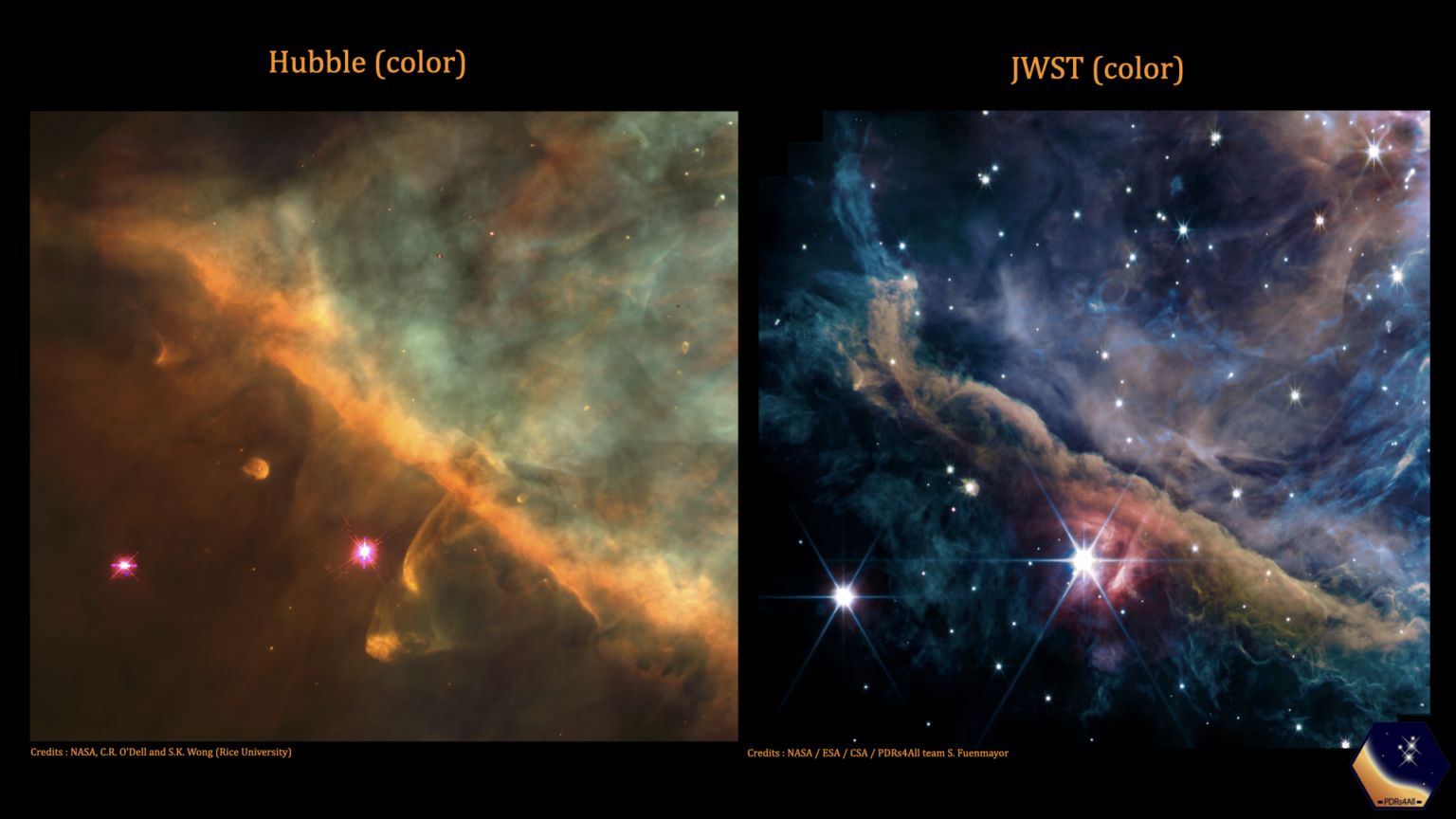

Now, the most powerful space telescope ever built has given us a new gaze into the heart of the Orion nebula.

The new images obtained by the James Webb Space Telescope's NIRCam are, astronomers say, the most detailed and sharpest we've seen yet. Analysis is ongoing, but we're expecting to learn something new and fascinating about this incredible part of the galaxy.

"We are blown away by the breathtaking images of the Orion Nebula. We started this project in 2017, so we have been waiting more than five years to get these data," says astrophysicist Els Peeters of Western University in Canada.

"These new observations allow us to better understand how massive stars transform the gas and dust cloud in which they are born. Massive young stars emit large quantities of ultraviolet radiation directly into the native cloud that still surrounds them, and this changes the physical shape of the cloud as well as its chemical makeup.

"How precisely this works, and how it affects further star and planet formation is not yet well known."

Star formation is a very gassy, dusty process. Baby stars are born from dense clumps in clouds of dust and gas that collapse under gravity and start to accumulate material from the cloud around them, forming a disk as the star spins.

The very nature of this process means it's hard to see: all that dust and gas blocks light from escaping out to show us what's inside.

However, the longer wavelengths of infrared light, the range through which JWST views the Universe, are able to penetrate dust, which gives us a view into regions impossible to see in shorter wavelengths, such as the visible spectrum.

Scientists have, therefore, been very excited to use the telescope to study star formation and learn new details about the process that have heretofore been difficult to see.

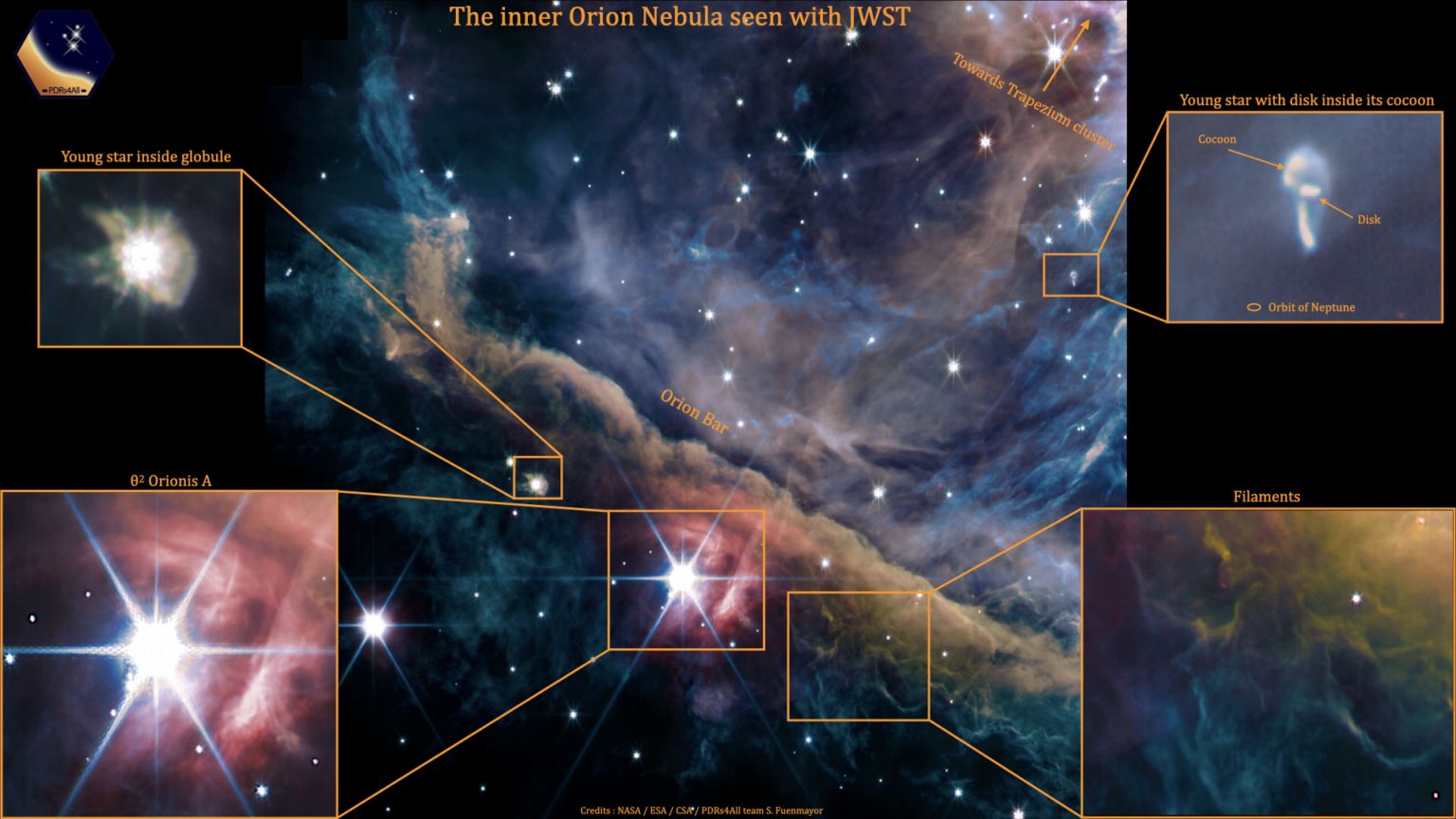

The new image focuses on a structure called the Orion Bar, running diagonally from the top left to the bottom right. Light from a cluster of young, hot stars called the Trapezium cluster illuminates the scene from the top right corner; this harsh, ionizing ultraviolet light is slowly eroding the bar away.

This is one of the processes involved in what astronomers call feedback – when wind or radiation from a stellar object pushes material away, reducing or quenching star formation. They also produce complex shapes and structures in a molecular cloud, including filaments and cavities, both of which have been captured in the new image.

Other objects in the image include globules (dense clumps of material with baby stars inside) and a young growing star with a disk of material around it. That disk is being evaporated from the outside by the radiation from the Trapezium stars. Nearly 180 of these objects, called proplyds, have been found in the Orion nebula.

The brightest star you see in the image is called θ2 Orionis A, and it's one member of a multiple-star system next to the Trapezium Cluster, which is also known as θ1 Orionis. Interestingly, θ2 Orionis A is also, in itself, a triple-star system.

Although it appears very bright in the JWST image, θ2 Orionis A can only be seen by the naked eye from Earth in regions not significantly affected by light pollution. Nevertheless, it's very hot, over 100,000 times more intrinsically bright than the Sun.

Its light is bouncing off dust around it, creating a pretty red glow.

"We clearly see several dense filaments. These filamentary structures may promote a new generation of stars in the deeper regions of the cloud of dust and gas. Stellar systems already in formation show up as well," says astronomer Olivier Berné of the Institute of Space Astrophysics in France.

"Inside its cocoon, young stars with a disk of dust and gas in which planets form are observed in the nebula. Small cavities dug by new stars being blown by the intense radiation and stellar winds of newborn stars are also clearly visible."

Deeper analysis will, hopefully, tell us more about the many and varied processes that we can see occurring in this image. Our Solar System is thought to have been born in an environment similar to the Orion Nebula; so, in turn, these future studies might reveal more information about how our Sun formed, and the stardust that made up Earth and all the planets.

"We have never been able to see the intricate fine details of how interstellar matter is structured in these environments, and to figure out how planetary systems can form in the presence of this harsh radiation," says astronomer Emilie Habart of the Institute of Space Astrophysics.

"These images reveal the heritage of the interstellar medium in planetary systems."

We'll be waiting eagerly on those findings. Meanwhile, you can download the full-size images from the website of the Early Release Science program Photodissociation Regions for All.