The iconic Australian kangaroo hops with its powerful hind legs across the outback or in front of your car at dusk. But scientists say that not so long ago (evolutionarily speaking, anyway), extinct large kangaroos likely used other modes of transportation, like walking on two legs or all fours.

Researchers from the Universities of Bristol and York in the UK and Uppsala University in Sweden used fossil evidence and a new analysis of shin and ankle bone data to find out how macropodoids (kangaroos, wallabies, and their relatives) moved over the past 25 million years.

The team's published review says the signature hop of the famous Qantas Airlines 'flying kangaroo' that "many people regard as the pinnacle of kangaroo evolution", actually represents just one of the many ways these astonishingly mobile animals evolved to be successful in different habitats.

"In fact, modern large hopping kangaroos are the exception in kangaroo evolution," says vertebrate paleontologist Christine Janis from the University of Bristol, lead author of the study.

"Large kangaroos were much more diverse as recently as 50 thousand years ago, which may also mean that the habitat in Australia then was rather different from today."

Kangaroos are the only large mammals that get around primarily by hopping on two legs. This form of locomotion is intriguing to scientists. Janis and her colleagues say much of the research so far has focused on the larger-bodied kangaroos, leaving a gap in our understanding of their smaller-bodied counterparts.

The researchers dug into the fossil record to examine the weight-bearing shin bones (tibia) and heel bones (calcaneus) of kangaroos and their marsupial relatives to show how hop traits changed over time, separate from growing body mass.

Their analysis suggests modern large-bodied kangaroos' signature higher-speed endurance hopping was rare or absent in all but a few lineages, including the direct ancestors of red and gray kangaroos.

Early macropodoids that lived 25–50 million years ago were small and could bound, climb, and hop to some extent. Around 10 million years ago, with an increasingly arid climate and open habitats, larger-bodied macropodoids emerged.

Modern kangaroos have since reached an optimal mass for efficient hopping – the red kangaroo (Osphranter rufus) weighs up to 90 kilograms (198 pounds), and male eastern gray kangaroos (Macropus giganteus) are around 66 kilograms. But many extinct kangaroos were well above these sizes, and here's the twist: hopping becomes a real challenge for larger sizes.

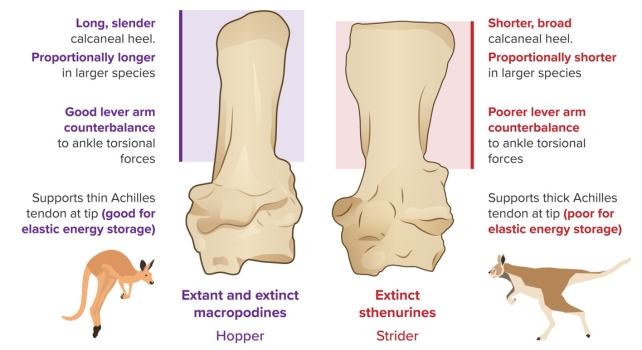

The larger kangaroos of the past could either evolve more specialized anatomy, like long slender heel bones for efficient higher-speed hopping, or they could use other locomotion methods at higher speeds to cross more terrain, as two extinct lineages did.

The 'short-faced kangaroo' sthenurine, which split from modern kangaroos 15 million years ago, appears to have adopted bipedal 'striding' and managed this at all speeds; it did not have the heel capacity to lug their whopping weight along at a hop, however. The largest of them, the largest known macropodoid to ever exist, Procoptodon goliah, weighed in at over 200 kilograms.

The protemnodons, closely related to modern large kangaroos, had short, broad feet like tree kangaroos that didn't lend themselves well to hopping, and they likely mostly walked on four legs.

Having elongated heel bones helps to resist rotational forces in the ankle when hopping, and a thin-tipped Achilles tendon gives modern kangaroos a spring in their hop. But the broad heel bones of these two extinct groups suggest they stood more upright than today's crouched kangaroos.

"What makes modern endurance-hopping kangaroos appear so unusual is the geologically recent extinction of similar animals who moved in different ways," Janis says.

All kangaroos today still use quadrupedal locomotion for traveling slowly, which in larger species becomes pentapedal, using their tail as a fifth limb. With the Late Pleistocene extinctions of larger animals (in Australia and elsewhere), kangaroo gaits became less diverse.

"The assumption that increasing continent-wide aridity after the end of the Miocene selectively favored hopping kangaroos is overly simplistic," concludes Janis.

"Hopping is only one of many gait modes employed by kangaroos both in the past and today, and the fast endurance hopping of modern kangaroos should not be regarded as some 'evolutionary pinnacle'."

The review has been published in Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology.