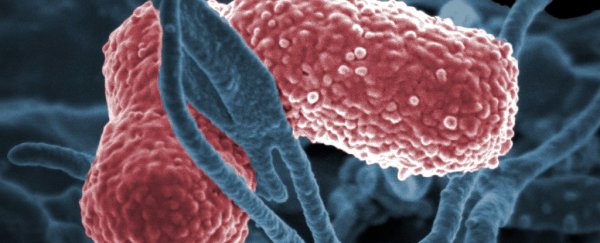

Klebsiella pneumoniae isn't always dangerous. But when it is, it's pure nightmare fuel.

Outside of its happy home in the gut the bacterium can cause a bunch of problems, not least the flesh-destroying horror that is necrotising fasciitis, capable of killing a perfectly healthy person within days. As if that's not enough, there's a strain we really need to watch out for.

Usually K. pneumoniae is right at home as an enteric bacterium floating around lazily inside the human digestive tract, occasionally showing up in the mouth or on the skin.

It's not exactly uncommon as far as bacteria go, and typically makes itself known as a common hospital infection in people who are already suffering a kick to their immune system.

But then, a rather aggressive variety of the bacterium was found emerging in Taiwan in the 1980s. One that didn't require the host to be sick and resulted in brain and liver abscesses and necrotising fasciitis.

Unfortunately the hypervirulent strain of K. pneumoniae (hvKp) doesn't exactly wave a coloured banner announcing its arrival. Until now there's been no way to tell whether a garden variety K. pneumoniae infection is a souped-up hvKp strain in disguise, at least until the damage is done.

So researchers propose using the next best thing; a test for chemical markers that can tell the two apart.

Thomas Russo is head of the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Buffalo. Together with researchers from around the world, Russo found a combination of microbial name-tags buried in the hvKp's DNA that could be used to reliably identify it.

While the research is looking solid, it's just the first step in the process.

"Presently, there is no commercially available test to accurately distinguish classical and hypervirulent strains," says Russo.

"This research provides a clear roadmap as to how a company can develop such a test for use in clinical laboratories. It's sorely needed."

Sorely needed is an understatement. A multidrug resistant (MDR) form of K. pneumoniae has been on the radar of pathologists for a few years now; it makes even last-line antibiotics a lost cause.

It's bad enough that the World Health Organisation considers it a top priority in developing an antibiotic that will keep it under control. So far the MDR strain has kept a relatively low profile, but its prevalence is increasing and health organisations are on high alert.

If hvKp were to learn the secret to resisting last line antibiotics… well, we'd be in trouble.

So, having a test to distinguish the hypervirulent strain would clearly be a win for patient care. But the big picture would be to give it to epidemiologists so they can track its prevalence as it creeps around the globe, and keep a vigilant eye over drug resistance in its population.

This could occur in one of two ways. One is for the two strains to come into close proximity and have the MDR variety drop its coding for resistance into the environment, where hvKp picks it up like it's a recipe dropped into its mailbox.

The reverse can happen as well – the MDR variety could possibly acquire the skills to turn into a flesh-eating villain.

Which is precisely what happened recently.

"The latter mechanism is what caused the deaths of five patients in the intensive care unit of a hospital in Hangzhou, China, which was reported early this year," says Russo.

There's a lot to learn about the hypervirulent strain. More cases have been reported in Asian countries than elsewhere, but it's unclear whether that's because it's rampant there or because of some susceptibility in the population.

More research will tell, especially with a test on the way that will easily pick out hvKp.

Having eyes on the ground is only part of the solution, of course. We need to stem the superbug tide, while finding new drugs to combat the resistant strains that already exist.

This research was published in the Journal of Clinical Microbiology here and here.