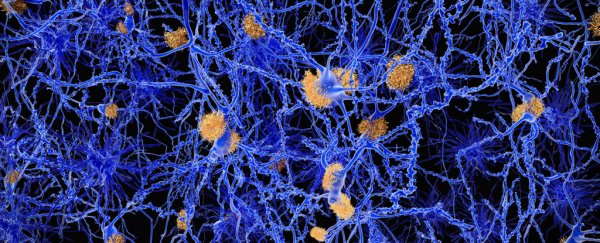

One of the hypothesised causes of the mental deterioration associated with Alzheimer's disease is amyloid beta – a sticky protein that congregates on surfaces in the brain, forming hardened plaques and impeding neural communication.

But there's new hope that these plaques can be removed after they've formed, with a study by researchers at the Korea Institute of Science and Technology discovering a chemical that can break amyloid plaques down in the brains of mice, improving the animals' learning and memory functions.

The chemical, called EPPS, is similar to taurine, which is used in energy drinks like Red Bull. When it was added to the drinking water of mice that showed symptoms of Alzheimer's disease (after having had their brains injected with amyloid plaques), the animals demonstrated better performance in maze and behavioural tests in contrast to untreated mice in a control group.

After seeing how the mice performed in tests, the researchers sectioned and stained their brains to help visualise the presence of amyloid beta plaques. They found that adding EPPS to the mice's daily drinking water had significantly reduced the levels of amyloid beta plaques in the mouse brains and substantially eliminated the formations at high doses.

"Our findings clearly support the view that aggregated amyloid beta is the pathological culprit of Alzheimer's disease," lead researcher YoungSoo Kim told Ian Sample at The Guardian. The study has been published in Nature Communications.

At a molecular level, EPPS binds to amyloid beta formations and disaggregates them by converting the proteins into monomers (singular molecules). The chemical travels in the blood to the brain and is able to permeate the blood-brain barrier due to the small size of its molecules.

While the artificial Alzheimer's induced in the mice via amyloid injections can't be equated to the more pervasive degeneration that occurs in humans when the proteins clump together naturally over long periods of time, the EPPS treatment still offers hope that further research with the chemical may provide more answers.

It's early days yet, as it's not fully understood whether EPPS will be safe to administer to humans (although it didn't produce significant side effects in the mice), nor whether the compound will deliver similar cognitive benefits in people.

"I do not believe EPPS or other amyloid clearing drug candidates will make Alzheimer patients recover their damaged brains," said Kim. "However, I strongly believe these drug candidates will halt the neurodegeneration and rescue patients from death."